Welcome to the fifth instalment of Czapp’s course on futures market spreads.

In previous explainers we looked at what a spread is, why they are relevant to market participants and analysts, and what the key drivers of futures market spreads are.

In this explainer we will cover the specific drivers of the No.11 raw sugar futures May-July spread.

No.11 Raw Sugar Futures Contract

There are four No.11 raw sugar futures contracts traded in a calendar year, the March, May, July, and October contracts. This means there are four spread pairs between neighbouring contracts, the October-March (V/H), March-May (H/K), May-July (K/N), and July-October (N/V).

For more information on the No.11 raw sugar futures contract, please see our explainer.

May-July Spread Overview

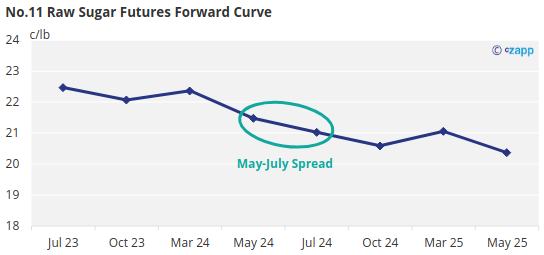

Given the contract months involved, the May-July spread is relevant to supply and demand in the raw sugar market from the end of Q2 to Q3.

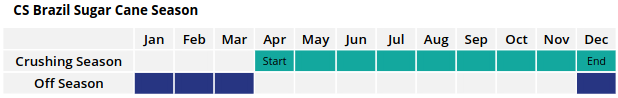

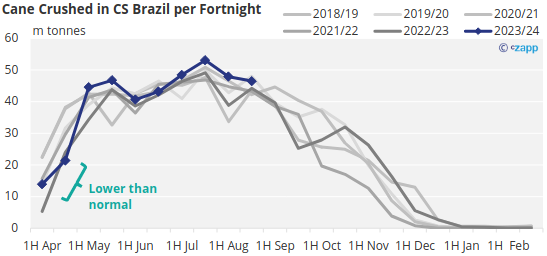

Since the May contract coincides with the start of the CS Brazil sugar cane harvest (the world’s largest producer and exporter of raw sugar), the May-July spread is another that is affected by how early or late their crop begins, and how much the world demands their new season supply.

The earlier that mills can begin crushing uninterrupted, the more sugar there will be available against the May contract.

This said, even in the case of an early starting cane crush, there is still generally more supply available around the July contract when operations will have reached their peak.

As a result, given how important the crop season in CS Brazil is to the raw sugar markets it tends to mean that, like the March-May spread, the May-July spread trades at a premium.

Who has Sugar to be Delivered into the Expiry?

Sugar priced against the May raw futures contract generally aims to be delivered in late Q2-Q3. For sugar specifically delivered through the exchange the delivery window is precisely 75 days long, from the 1st of May to around the 15th of July. To understand the distinction here is an explainer on what futures markets are used for.

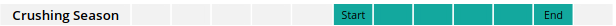

The May expiry tends to be dominated by CS Brazilian sugar, by this stage in the year Central American producers generally don’t have much availability, whilst Indian and Thai sugar is less likely to be delivered into the exchange even if there is availability.

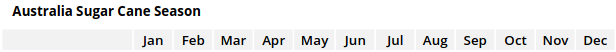

Additionally, the Australian crop season will not yet have started by the time of the May expiry.

This means that for those receiving sugar from the exchange, they can be somewhat sure they are receiving Brazilian raws, making the May expiry fairly ‘clean’.

What Should be Paid Attention to?

The May contract represents the start of new season supply from CS Brazil.

This means that both when the CS Brazil cane crush is able to get underway fully, and how much the world needs this supply are key determinants for how large of a premium the May-July spread will trade at.

For understanding how effectively the new CS Brazil can get started the following are considered:

- How much stoodover (uncrushed) cane there is from the previous season.

- Whether rains at the end of the off-crop interrupt initial field operations.

- Whether mills prioritise sugar or ethanol production at the opening of a season.

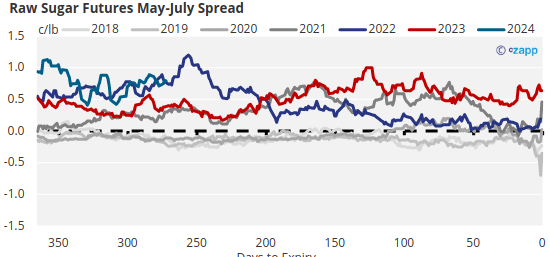

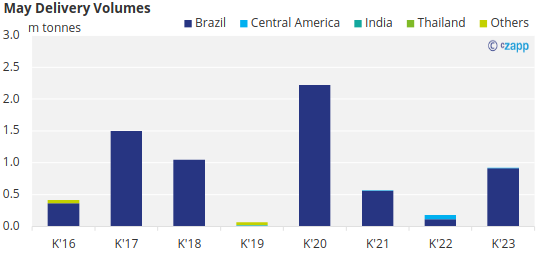

The start of the 2023/24 season was impacted by early season rains which limited access to the fields during the first few weeks of the season. As such it saw one of the slowest starts to the season in recent years despite intentions to start as early as possible.

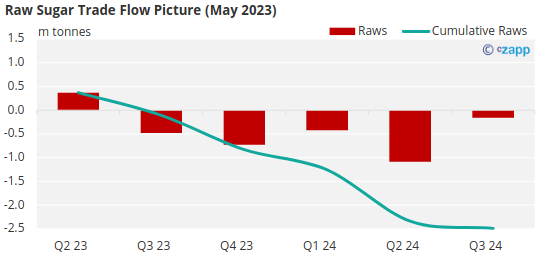

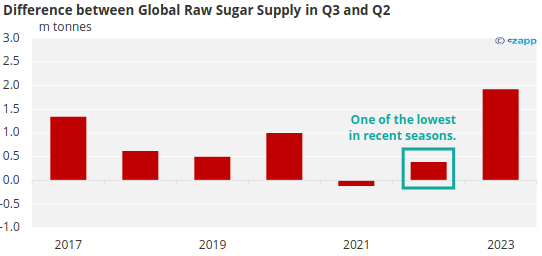

At the same time there was a greater dependence on CS Brazil sugar as part of the broader undersupply facing the raw sugar market at the that stage. A snapshot of our global supply and demand forecast from May 2023 showed the expectation of a deficit of sugar from Q3 2023 onwards.

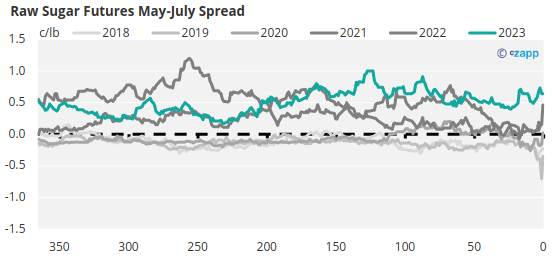

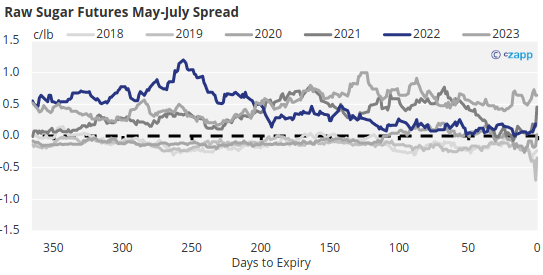

This helped keep the May-July spread trading at a comfortable premium over the final few months before the May 2023 contract expired as new crop CS Brazil sugar was slower to hit the world market.

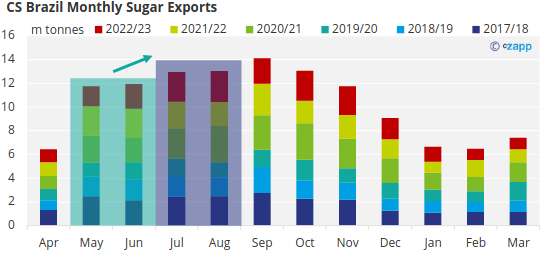

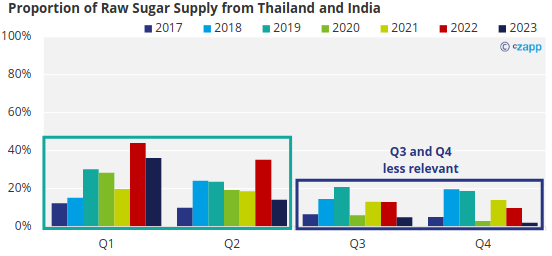

Attention on occasion should also be paid to India and Thailand, regularly the 2nd and 3rd largest exporters of raw sugar annually. Both export the majority of their sugar in the first half of the year, meaning that in exceptional years they can weigh heavily on the May end of the May-July spread.

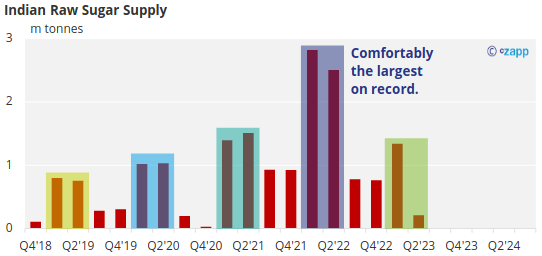

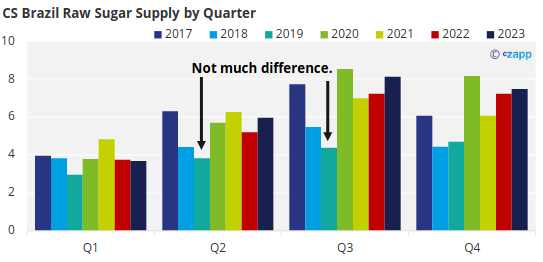

The 2021/22 Indian crop saw record production, and record sugar exports. Indian mills were able to supply the market with almost double the volume of sugar in Q2 of that year compared 2021, itself a strong export season.

This meant that along with Thailand, combined supply in Q2 2022 jumped from around 20% of total raw sugar supply over the previous five seasons, to closer to 40%.

It also meant that there was a smaller than normal differential between total world supply in Q3 and in Q2.

This helped the 2022 May-July fall away toward neutrality over the last 250 days toward its expiry as more and more news flow about how good the Indian crop looked came out and relative demand for new season CS Brazil sugar waned.

Exceptions to the Rule

Whilst the May-July spread more often than not trades at a premium due to the start of the CS Brazil season, there are instances where this isn’t the case.

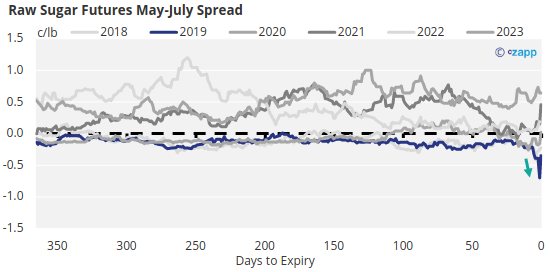

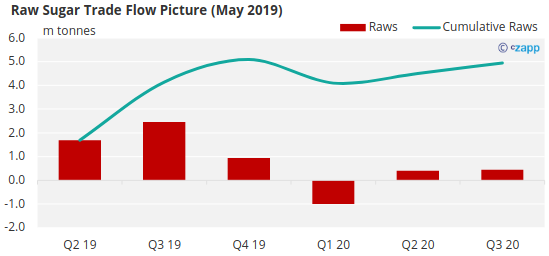

The 2019 May-July spread traded at a discount throughout its final year before weakening further in the last 30 days before expiry.

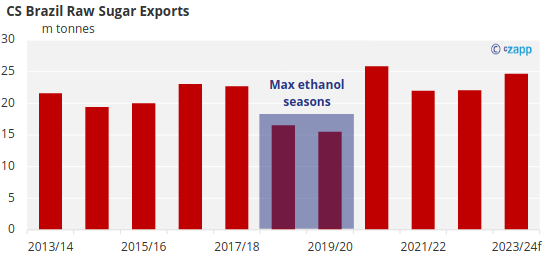

Weak sugar prices at the time meant mills in CS Brazil minimized their sugar production to maximize ethanol production for the 2019/20 season.

This meant fewer exports and less of a difference in supply in CS Brazil in Q2 vs Q3. A smaller difference in supply between the May and July contracts meant less reason for the May-July spread to trade at a premium.

More broadly, weaker sugar prices were a symptom of a massive oversupply of sugar. In May 2019 there was a forecast raw sugar trade surplus of 5m tonnes by the end of 2019.

This was also a function of weak demand, major buyers China and Indonesia were not being allocated import licenses quickly, whilst the sugar white premium was also particularly weak meaning there wasn’t much incentive for re-export refiners to buy raw sugar either.

As a result, it was likely that a major trade house aiming to receive sugar from the May 2019 contract expiry realized that they might be receiving a lot of sugar without an obvious place to sell it on to. The trade house would have needed to sell out of their long positions to avoid this happening.

Since liquidity in a contract gets much worse the closer it is to expiry it is likely that this selling pressure had an outsized downwards affect on the May contract, weakening the May-July spread sharply.

If you have any questions, please get in touch with us at Jack@czapp.com.