Opinion Focus

- Aflatoxin can affect poorly stored and processed peanuts.

- It is carcinogenic/mutagenic in humans and animals.

- In recent years Brazil has enhanced its aflatoxin controls for peanuts.

Aflatoxins are a group of toxins produced by fungi of the Aspergillus genus. They are carcinogenic/mutagenic to humans and animals. Their story began to be told in the 1960s, when a disease, until then little known, killed thousands of turkeys in the United Kingdom. Researchers discovered that the villain was aflatoxin.

Aspergillus fungi grow in soil and on various major foods such as sweetcorn, wheat, rice, peanuts and sesame seeds. In the case of the bird contamination in England, grain had been imported from Brazil, which was a red flag for European importers. Since then, control of aflatoxins has become stricter, and the substance has gained worldwide fame.

Despite significant progress in containing the problem, Brazil is still struggling to get rid of its bad reputation. Only in January last year did the EU remove Brazilian peanuts from the list of high regulatory control for importing foods from certain origins. And this was only possible thanks to the implementation of measures to mitigate the incidence of contamination.

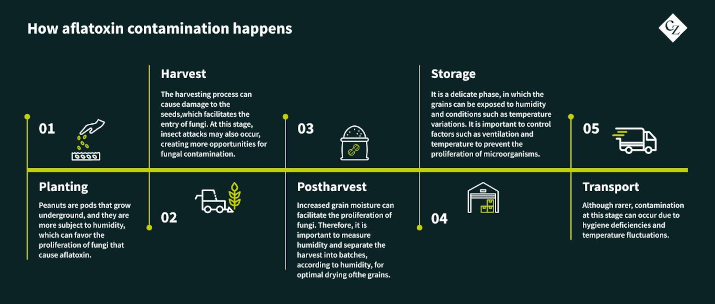

How Contamination Occurs

One of the main initiatives was to identify improvements in the conditions for harvesting, drying, and storing grain, which are the phases most susceptible to contamination. While research and control measures progressed, however, fears of contamination in humans did not dissipate to the same extent.

Some myths still persist. One of them is that heating the peanuts eliminates mycotoxins. The answer is no, as fungi resist high temperatures and do not decompose when cooking or roasting.

Another common question: do mycotoxins change the appearance, flavor, and odor of food? Although they can cause mold and mildew, aflatoxins do not necessarily cause such obvious effects, which represents yet another reason for strict control of the substance.

Mitigating the Problem

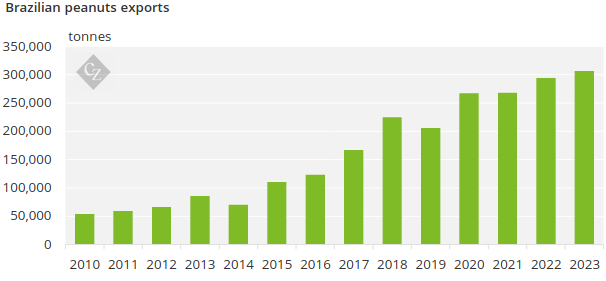

In Brazil, where peanut production and exports have soared in recent years, containing the problem involved changes in legislation, with the launch of quality certificates and more rigorous production and marketing protocols.

Source: Comex.

“Today, we have one of the strictest toxin limits in the world, largely to meet European standards,” says Dartanha José Soares, a researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), involved in research and measures to control aflatoxin.

To achieve this, it was necessary to modify the legislation and establish more effective control protocols, which provide for audits at all stages of the peanut production, transport, storage, and processing process.

One of the most important milestones was the creation of a Ministry of Agriculture protocol that defines the maximum aflatoxin limit of 4 µg/kg for peanuts exported to Europe. The standard also provides for audits at all stages of grain production and processing. “In practice, the production chain has worked with a maximum limit of 2 µg/kg. Thus, there is room for a margin of error without violating the requirements of the European Union”, explains Soares.

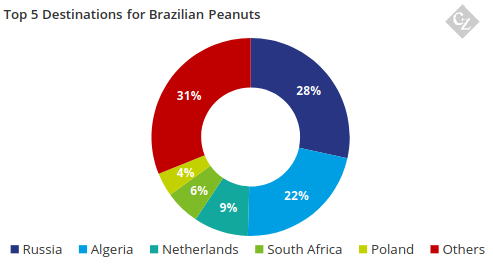

Source: Comex.

The concern with meeting European demands has a very objective reason. European countries, especially the Netherlands, represent one of the largest markets for Brazilian peanut exports.

Large companies that process peanuts have invested in technologies, such as sensors that measure temperature and humidity, to keep the environment in which the nuts are processed under control.

Peanut separation by machinery. Source: Embrapa/publicity photo.

Good practice measures in the planting and management phase, in the field, have also contributed favorably to the control of aflatoxin. It is also important to remember that certificates, such as the quality seal launched by the Brazilian Association of the Chocolate, Peanut and Sweets Industry (Abicab), are viewed favorably by the market.

The European market, in turn, works with internationally recognized certificates, such as the British Retail Consortium Global Standards, Food Safety System Certification and Safe Quality Food Certification. Although from a legal point of view these certifications are not mandatory, they are increasingly valued by importers.

Regarding the levels of aflatoxin accepted by countries that are not part of the European Union, there is a variation. In India, for example, the maximum limit is 30 µg/kg, while in Australia it is 15 µg/kg and in China, 20 µg/kg. South Korea and Japan, in turn, set a limit of 10 µg/kg.