Insight Focus

- Simplifying the wheat market helps to understand it.

- Each market is different, but they are often less complex than they seem.

- Understanding wheat futures allows more efficient global agri-trade.

Anyone involved in an agrifood business, or the supply chain as a whole, will hear about wheat markets. There are ups and downs, as well as the big headline stories relating to weather extremes, global politics or conflicts.

The basic workings of the markets are not always as well understood as people may believe. While many businesses know that wheat prices impact their costs and profitability, they lack a real grasp of how to manage that risk. There is often a lack of relatively basic knowledge to manage the financial implications, which can be significant, as wheat markets drive prices up and down.

Understanding the basics of the wheat markets can considerably improve the ability to protect business profitability when prices rollercoaster up and down.

Defining the Wheat Market

We have all heard about futures or derivatives markets. Do not be alarmed, they are fundamentally quite straight forward.

There are a number of quoted wheat futures markets covering all corners of the world. Each have their own specifications and individuality.

The various futures markets around the world allow participants throughout the supply chain, from producers to retailers, to manage their price risk and protect their businesses.

Agricultural futures markets were the first to exist, with the express intention of enabling a seller to sell or a buyer to buy:

- a defined quality commodity

- at a defined price

- at a defined point of time in the future.

How does this work in practice?

1. Seller – The Farmer

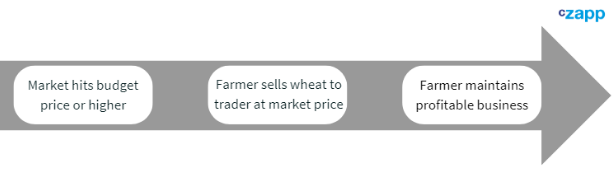

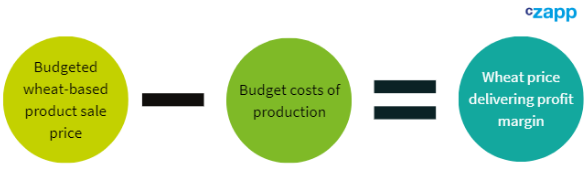

Farmers grow wheat year on year. They have a generally good grasp of various costs of production, which allows them to draw up a budget that will hopefully provide an appropriate profit margin.

With this budget in mind, the farmer will know that they need to empty a wheat store, whether for logistical reasons or to cover budgeted costs, at a given point of time in the year ahead.

The farmer will usually have a relationship with a wheat trader who can price the farmer’s wheat on any given working day of the year.

Through discussion with the wheat trader, or with knowledge of how a particular futures market relates to the price of his wheat, the farmer can sell wheat as needed to the trader.

The farmer-to-trader wheat contract will stipulate, as a minimum:

- Commodity, e.g. wheat – feed/milling, hard/soft.

- Specification, e.g. moisture, kg/hl, admixture.

- Contract period, e.g. one calendar month for collection ex farm.

- Price of wheat per tonne (or other weight denomination).

2. Buyer – The user/processor

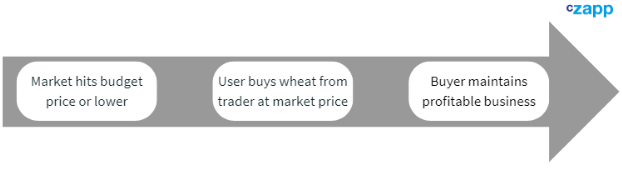

In a similar way, a user or processor will know his operating costs and will be able to work out his ability to sell the wheat-based product at a budgeted price.

The buyer is thus, in a comparable way to the farmer, able to buy wheat at a budget-friendly level to maintain a profitable business.

The buyer’s contract with the wheat trader will similarly state:

- Commodity, e.g. wheat – feed/milling, hard/soft.

- Specification, e.g. moisture, kg/hl, admixture.

- Contract period, e.g. a calendar month for delivery to user.

- Price of wheat per tonne (or other weight denomination).

3. Trader

It is useful to think of the wheat trader as the ‘facilitator’ in the supply chain.

The trader needs to be able to:

- Buy from the seller when the seller wants to sell.

- Sell to the buyer when the buyer wants to buy.

To enable this, the trader must manage his own price risk in relation to wheat market prices. The trader will use the relevant futures market to ‘hedge’ his position and manage price risk.

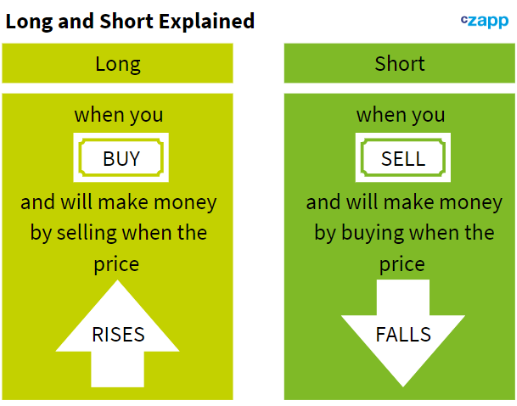

A trader can have a ‘position’ that is:

- Long – he has bought more than he has sold.

- Short – he has sold more than he has bought.

- Square – he has equal purchases to sales, thus no real price risk.

Hedging Made Simple

The trader inevitably has business costs and a need for margin. These are most easily defined in terms of unit of weight, e.g. per tonne.

There are also additional transport costs to move individual wheat parcels from the farmer (from whom the trader buys) to the user (to whom the trader sells).

The trader, having established his business, margin and transport costs, can then easily assess prices and the difference between the purchase price ‘ex farm’ and the sale price ‘delivered’ to the user.

There is subsequently a calculation to be made, relative to the appropriate futures market.

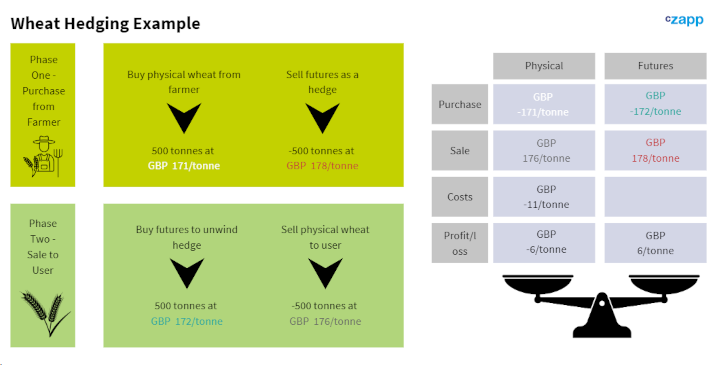

Example of Trader Hedging on the Futures Market

For our example, we will assume:

- The transaction takes place in the UK.

- The trader trades in feed wheat similar to the London Feed Wheat Futures Market.

- The collection/delivery period will be May 2024.

- Trader costs and margin are GBP 3/tonne.

- Transport costs are GBP 8/tonne.

- Therefore, total costs ‘ex farm’ to ‘delivered’ are GBP 11/tonne.

Wheat traders buy and sell every day. Each user destination will have its own value, which will be reflected in its relative price against the London wheat futures. We will assume that the prevailing tradeable price delivered to the user is London wheat futures +GBP 4/tonne.

Phase 1 – purchase from farmer

- Trader purchases 500 tonnes of feed wheat from farmer for collection in May 2024.

- London wheat futures price for May 2024 is GBP 178/tonne.

- Price delivered to user is futures + GBP 4/tonne = GBP 182/tonne delivered for May 2024

- Delivered price of GBP 182/tonne less GBP 11/tonne of costs = GBP 171/tonne purchase price to the farmer.

Phase 2 – sale to user

- Trader sells 500 tonnes of feed wheat to user for May 2024.

- London wheat futures price for May 2024 is GBP 172/tonne, now lower than on the day of purchase.

- Price delivered to user is futures + GBP 4/tonne = GBP 176/tonne delivered for May 2024.

The trader’s hedge has worked well, with the physical wheat loss of –GBP 6/tonne being negated by the futures wheat profit of GBP 6/tonne.

Summary

Physical and futures wheat markets work well side by side to allow global trade. They allow buyers to buy and sellers to sell at times of their choosing.

Traders, acting as ‘facilitators’, allow for this by managing their positions and hedging their physical wheat risk on the wheat futures markets.

Recent years have shown how market price volatility can be unmanageably difficult for businesses, but the agri-food industries have the enormous benefit of transparent wheat futures markets.

The challenge for those managing agri-food businesses is understanding what is relevant to them and how to turn it to their advantage.

It is often not as complex as it might at first appear.