Insight Focus

- Under Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, importers would need to purchase certificates that cover emissions made to manufacture products anywhere in the world.

- Importers will need to report “embedded carbon” in transition period to 2025.

- This has galvanised more countries to think about setting up their own carbon markets.

More Countries Follow EU Lead

Countries such as India, Indonesia, Turkey and Brazil have begun developing their own carbon markets in response to the European Union’s new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which came into force last month.

The CBAM covers means energy- and carbon-intensive materials, such as cement, iron and steel and fertilisers, must pay for the carbon emissions generated in their production, no matter where that took place.

From 2025. importers will have to buy CBAM certificates to cover emissions — which will be priced according to the most recent EU allowance auction price — and surrender them to the EU each year. Until then, importers are only required to report the “embedded carbon” in their products, an exercise that will help the European Commission build a dataset of all the major production facilities around the world for future use.

However, the CBAM legislation also allows for imports to earn exemption from CBAM charges if the country in which they are produced also puts a price on carbon emissions. This has led several countries to take a look at the mechanism. This week, the UK chancellor said the country will press ahead with its own system in 2026.

Carbon Allowances Don’t Incentivise Cuts

The European Union’s introduction of a CBAM has triggered a significant uptick in the development of carbon markets around the world, as more countries seek to put a price on carbon emissions that may help their industries sidestep Europe’s new carbon tariff.

The EU’s intention for CBAM is firstly to level the playing field between EU industry and its international competitors, and secondly to encourage more carbon pricing around the world.

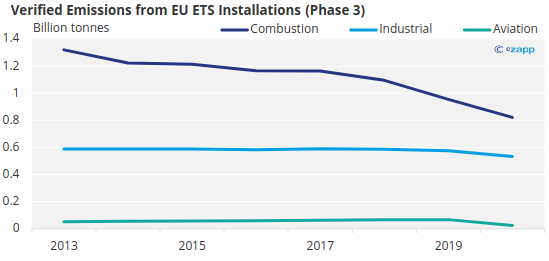

Most compliance carbon markets currently hand out emissions allowances free of charge to those sectors that are deemed to be at risk from international competition. This has meant that, according to data from the EU, industry is not cutting its carbon footprint as quickly as the energy sector.

Note: Aviation emissions in 2020 were impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Source: European Environment Agency

In order to drive more decarbonisation, the EU wants industry to fully absorb the cost of its emissions, but without impacting its international competitiveness, which is why the CBAM was born.

Other Measures Add Pressure

To be clear though, it’s not just the CBAM that’s driving this development. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is also building a global carbon credit market that will help more than 190 countries achieve their published climate goals.

This market, known as Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, allows countries to sell surplus emission certificates to other countries that are falling behind their targets, and is expected to spark an explosion of interest in projects that reduce, avoid or remove carbon.

In order to kill two birds with one stone, many emerging economies are working feverishly to set up domestic carbon markets that will enable them to both water down the impact of Europe’s CBAM, but also to participate in the UN’s Article 6.4 market.

There are significant differences between the compliance markets in places such as Europe, California and the UK, and the new markets springing up. The existing compliance markets enable trade in carbon allowances, which represent the legal permission to emit greenhouse gases. The supply is limited and shrinks each year in line with mandatory reduction targets.

The new markets are for carbon credits, which represent the reduction, avoidance or removal of carbon dioxide, rather than a specific, mandatory target. Companies will be required to buy credit matching their emissions in order to comply, but the supply of these credits will not be limited.

Presently, various popular types of carbon credit trade at between USD 1/tonne to USD 20/tonne; the market price in these emerging markets will depend largely on the type of credits allowed for compliance.

But early indications suggest that most, if not all, of these markets will generate a significantly lower price on emissions than the EU’s current price of EUR 78/tonne (USD 83/tonne), and that most imports to Europe will therefore still attract a border charge.

That’s because the EU legislation specifies that “imported products are subject to a regulatory system that applies carbon costs equivalent to those borne under the EU ETS, resulting in a carbon price that is equivalent for imports and domestic products.”