Insight Focus

- The Sustainable Foods London event took place on November 6 and 7.

- Panellists discussed a range of topics, from food waste to policy to carbon measuring.

- These are the key messages we took from the conference.

Czapp attended Sustainable Foods London, which took place on November 6 and 7. The event brought together industry leaders, policy makers, innovators and investors to share best practices and discuss the sustainable opportunities and challenges facing the food and beverage sector. Here are the main lessons we learned.

1. Food Systems Need a Fundamental Redesign

“We are really good at producing calories but we’re sometimes less good at getting them to the mouths they need to feed,” said Henry Dimbleby Founder of food chain Leon and Non-Executive Director at DEFRA in his speech.

He stressed that we now produce enough calories for 8 billion people as we did for 2.8 billion people with just slightly more land.

Source: National Food Strategy

In terms of addressing sustainability, WRAP CEO Harriet Lamb said that some of the easier milestones have already been reached. “We need to be able to make those transformative leaps,” she said.

A rethink of existing food systems may need to put the farmer first, said Soil Association CEO Helen Browning. She added that, in the UK at least, it can be more financially beneficial for farmers not to produce food, which she called “worrying”. Ian Noble, Vice President R&D at Mondelēz International cautioned that “we don’t have a business if we don’t have farmers.”

Nina Prichard, Head of Sustainability & Ethical Sourcing UK at McDonald’s agreed that the financial burden of decarbonization shouldn’t all be on the shoulders of farmers. “We need to de-risk the financial burden,” she said. She emphasised the importance of the whole supply chain understanding the key metrics of farming businesses.

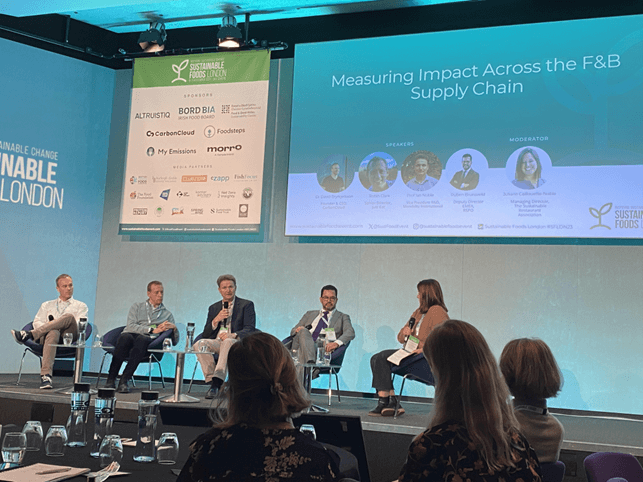

2. Measuring Emissions is Challenging

So, how do we redesign food systems? The answer was unanimous: it is going to be incredibly difficult. One of the most tangible ways that many companies are trying to do so is by measuring and benchmarking supply chain emissions.

The problem, said Adele Jones, Executive Director of the Sustainable Food Trust, is that different consultancies use different metrics, so companies have no way to compare. She suggested that a global farm metric could be used that allows all partied to agree on the most appropriate measurement.

Right now, the biggest challenge for companies is measuring scope 3 emissions – those that are a little less tangible than others.

This is where the focus lies for David Bryngelsson’s company CarbonCloud. For him, companies that are not proactive about measuring Scope 3 emissions risk losing market share. “Once governments start enforcing carbon trading, the industry will have to internalise those costs,” he warns.

MyEmissions and CarbonCloud have both begun to roll out front of label packaging that displays carbon intensity of food products on menus much like calorie labelling. There are drawbacks, says Bryngelsson, noting that there is no such thing as a carbon-free basket because the products just don’t exist.

But like anything, it’s not just about getting it perfect on the first try, said Saif Hameed of emissions data management software Altruistiq. “Nobody has accurate numbers. What matters is that we’re transparent about that process,” he said.

3. Food Waste Could Tip the Scales

Another way to rethink food systems is to address food waste. “If food waste were a country, it’d be the world third largest emitter behind China and US,” said Lamb. She suggested making changes that don’t necessarily promote bulk buying. One example would be making the price of loose fruit and vegetables comparable with products that can be bought in bags.

In London alone, food loss and waste before reaching the consumer is equal to around 1 million tonnes – about two-thirds of which is edible, said Wayne Hubbard of ReLondon. According to him, while a focus on recycling is beneficial, there needs to be more scrutiny on the upstream supply chain to help avoid waste in the first place.

Safia Qureshi, Founder & CEO of CLUBZERØ also believes that we need to get out of the mindset of recycling and move the focus upstream. She said that for food and beverage packaging in particular, there are significant challenges to recycling due to contamination and food grade requirements, so issues could be addressed by food processors and manufacturers instead. “We think the private sector will be the one to save us,” she said.

4. Investors Still Need a Strong Business Case

Understanding and improving emissions is already becoming business critical. Often, the exit for food and beverage entrepreneurs is to sell their companies to a large corporate. But, according to Ivan Farneti, Managing Partner of Five Seasons Ventures, these big companies have made ambitious emissions pledges and a company with a poor emissions record will find the system works against them.

Sophie Luck of JamJar Investments agreed that capital will only be provided to the best companies. “Investors have the power to build a portfolio they can be proud of — they can say no to companies with no positive impact,” she said.

It is no longer just about economic impact, but ESG credentials contribute to the overall assessment, said Daina Spedding of BGF. “The higher the score, the higher priority the investment is,” she warned. “Unless you prioritise sustainability, you won’t remain competitive.”

Ultimately, sustainability alone is not enough – companies need to balance it with a strong business plan, Farneti stressed. “If your company is going to go bankrupt in two years, it’s not sustainable,” he said. “If the business doesn’t stand on its feet, it’ll have no impact.”

5. Success Requires Integration, Collaboration

“We’ve sat on panels who argue that customers will pay more for this. They won’t,” said Robin Clark, Senior Director of food delivery company Just Eat. He said that, although 50% of customers say they want to be more sustainable, many equate that simply to recycling more

This means companies need to engage more with consumers to find out what is important and communicate priorities, said Prichard. “We do a lot of consumer research and that tells us climate is important,” she said. This prompted McDonalds’ switch to paper utensils and the upcycling of the fast-food restaurant’s cooking oil into biodiesel.

But young people want to know more about how their food is produced, she added, but translating that into consumer language is quite a challenge. “There are different levels of knowledge around sustainability but with our brand, scale and impact, we can make a change.”

It’s not just about communicating with the consumer, but also with the wider organisation, according to Simon Devaney, PepsiCo’s UK Sustainability Director. “The first step is convincing our own organisation to make the changes and these conversations are more sophisticated.” He stressed that sustainability departments shouldn’t be isolated in silos but rather integrated into every facet of the business.

And Noble added that everyone – as long as they intend to continue living on the planet – needs to act. For him, current limitations shouldn’t stop organisations from setting ambitious goals. “We’re talking about doing something we’ve never done before at a pace we’ve never done it,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we don’t do it.”