Opinion Focus

- Alcohol is made from sugar and grain waste from the port of Santos.

- Other ports, such as Busan, South Korea, have recycling programs in place.

- The objective is to meet sustainability goals and avoid sending waste to landfills.

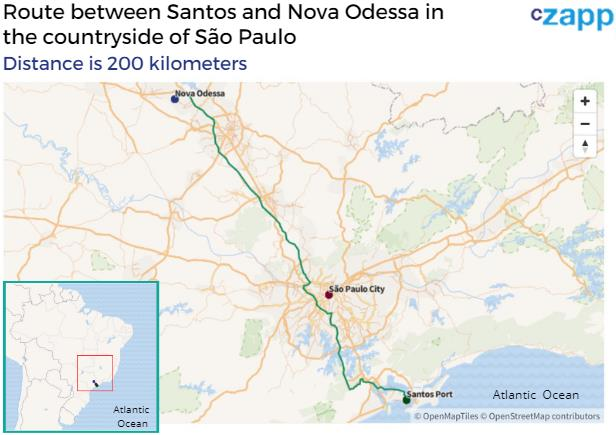

At least twice a week, suction equipment runs through the warehouses of Copersucar, one of the largest global sugar traders, in the port of Santos. They are on a special cleaning operation to collect sugar residues and send them for recycling. The waste is taken by truck to Nova Odessa, in the interior of São Paulo state, where it is transformed into eco-alcohol.

One of the main goals is to avoid the disposal of waste in landfills. The program, created in 2021, has been expanding. Today, around 100 tonnes of sugar and grain waste are sent monthly to the recycling facility.

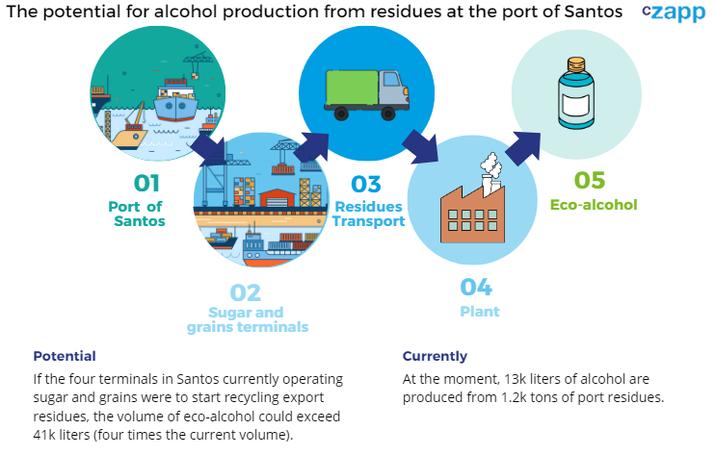

Upon arrival at the factory, the waste goes through a process of dilution in water, hydrolysis, fermentation, and distillation. 46% or 70% alcohol is then obtained.

This year, production should reach 13,000 liters, compared to 10,000 last year. Today, most of it is donated to Copersucar employees as hand sanitiser and the rest is sold.

The potential can be four times greater. For the time being, the Copersucar terminal is the only one with this initiative. If all the terminals that handle sugar and grains in the port of Santos adopted this practice, the volume of alcohol produced would be around 40,000 liters, enough to make almost 62,000 liters bottles of gel alcohol for hand sanitiser available in a year or 5,200 bottles per month.

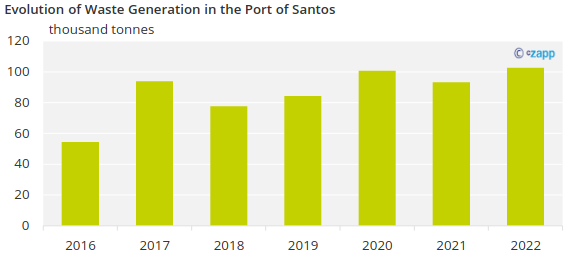

In any case, there is no lack of raw material to use in the manufacture of the product. Last year alone, the port of Santos generated 102.6 thousand tonnes of waste, 10.3% more than in 2021, following the growth of port activity itself. In 2022, 162.4 million tonnes of cargo were handled, a volume 10.5% higher than in 2021. The equation is simple. The more ships and cargo handling, the greater the amount of waste.

Source: port of Santos.

This is also a global issue. Over 80% of all goods traded in the world are transported by sea, according to the World Bank. Ships are responsible for about 20% of the garbage dumped in the oceans. The ships generate up to 300,000 tonnes of waste per year that end up at sea, according to estimates by the European Commission.

It’s no small thing. Therefore, recycling initiatives, in line with sustainability principles, have been implemented in some of the most important ports in the world.

As maritime transport increases, more ports should adopt waste recycling programs. Maritime trade is expected to grow 2.1% in the next four years, according to UNCTAD (United States Conference on Trade and Development). At the same time, the sector must continue to invest in green initiatives to meet compliance goals and the ESG agenda. Some ports are leading the way.

The Port of Saint John, the largest on Canada’s Atlantic coast, has launched an initiative to recycle marine ropes. In partnership with NGOs, the material is transformed into mats and baskets. Since 2021, more than 3,000 kilograms of ropes have been reused – the material was normally disposed of in landfills or at sea.

Port of Busan, South Korea. Source: iStock

The Busan port complex, in South Korea, in turn, created a PET packaging recycling program. In less than two years, 14 thousand PET bottles were collected. The material is decomposed and transformed into bags and blankets, donated to NGOs or needy communities. More than 10,000 bags have already been produced, according to the Busan port authority.

The port of Busan, which handled 22 million TEUs of containers last year, launched an ambitious expansion plan foreseeing investments of around USD 32 billion until 2050. Most of the resources should be used for the creation of new berths and automated container terminals, but there will also be room for investments in recycling and ESG goals.

One of the ideas is to implement an innovative alternative energy generation system, by transforming the electromechanical energy generated by trucks passing through the port into electricity. The cost of these projects, however, is often a hindrance.

In the Netherlands, the port of Amsterdam evaluated a process to turn plastic into diesel. Manufacturing would take place in a plant specially created for this purpose. Investment for the project, however, was estimated at tens of millions of dollars, and it did not go ahead. In terms of recycling in ports, the future in the short and medium term is in low-cost programs that can be implemented quickly.