Opinion Focus

- New law prohibits food imports from areas with deforestation.

- New audits and traceability processes can add to food production costs.

- Brazil, the main supplier of agricultural products to Europe, is preparing for new regulations.

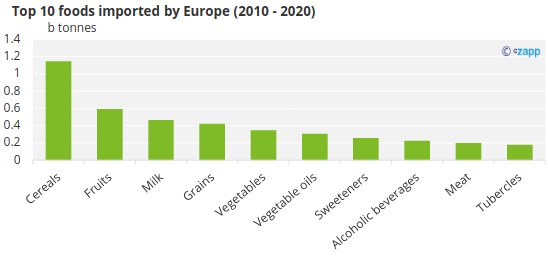

The prospect is tempting. From December 2024, some foods sold in European supermarkets, such as coffee and chocolate, will need to come from areas without deforestation. So says a new law, approved in April by the European Parliament, which prohibits the import of agricultural products from areas where native forests have been cut down. The rule, expected to come into effect in a year and a half, regulates the import of coffee, cocoa, soybean, beef, rubber, palm oil and wood.

Source: FAO

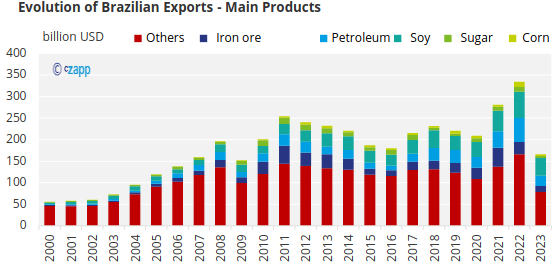

In Brazil (largest supplier of food to the European Union) the new legislation has been at the centre of a debate about new demands from international trade and commodity exports, which are essential for the Brazilian trade balance. In 2022, commodities (especially soybean, crude oil and iron) accounted for 68% of Brazilian foreign sales, generating around USD 227.2 billion. Soybeans alone accounted for USD 46.6 billion in exports (when soybean meal and oil are included, the total reaches USD 60.9 billion), 20.8% more than in 2021.

Source: Comex

In this scenario, any change in European Union rules requires extra care and attention. The problem is that some details of the new law aren’t clear. It is still not clear, for example, how sophisticated the tracking of production chains and sustainability practices should be.

“There may be additional costs with more sophisticated audits”, says lawyer Rodrigo Lima, partner-director of Agroicone, specialists in international negotiations, environment, and sustainability in agriculture. “In any case, it is a trade standard that could be adopted by the United States and China, so food producing countries will need to adapt”.

Read the interview below.

Rodrigo Lima, a lawyer specializing in international trade. Publicity photo.

How is Brazil positioning itself in relation to the new European law?

First, it is important to understand Europe’s position. The European Union is a major importer of food and, if deforestation associated with agricultural production is not controlled, it will not be possible to meet decarbonization targets. We should use this new law as an opportunity to better prepare ourselves for a new emerging demand. Countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States are also moving in the same direction. In the future, China may also do the same. In short, what Europe is asking for is that environmental laws be respected.

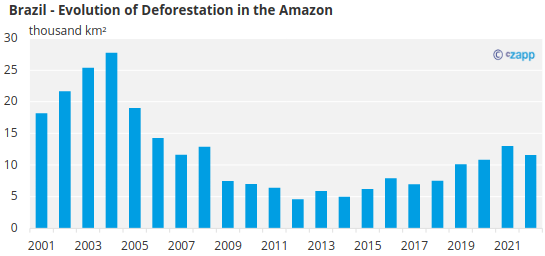

Source: Prodes

How will the new guideline work in practice?

The European Union will define countries and areas with a higher or lower risk of deforestation. It will be up to the importer to decide who they will buy from, which has to do with the degree of risk they will have to face. Another important point is that there will be fines for importers who buy food from areas with deforestation. It should be clarified that this is an extraterritorial rule. So, the European Union is regulating something in other territories, which may be questionable from an international law point of view. It is a beautiful legal discussion.

The law makes no distinction about legal and illegal deforestation, right?

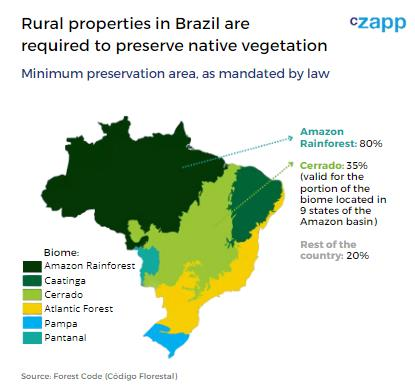

The law deals with food production in areas with deforestation practiced until December 31, 2020, whether or not allowed by the legislation of the producing country. In Brazil, we have a law that discusses the percentage of vegetation suppression in each biome, the Forestry Code. In the Amazon, for example, it is necessary to preserve 80% of the rural property area. But Europe’s new food import law says there can be no deforestation, regardless of whether it’s legal or illegal.

In this sense, can this law be interpreted as an obstacle to the expansion of new agricultural areas?

Yes. Countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia are arguing that the new European standard restricts access to international markets. This is an issue that could generate lengthy discussions at the WTO (World Trade Organization). But it must be remembered that these debates last for years.

What criteria will the European Union use to define risk areas?

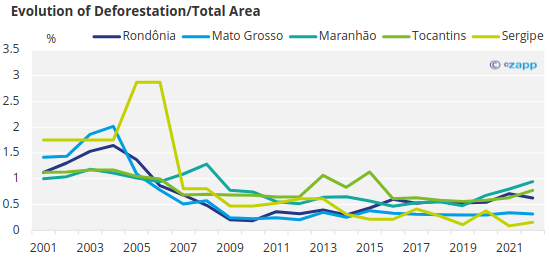

It will be the recent history of deforestation. The Amazon, for example, should be an area of high risk, which could cause a problem for a state like Mato Grosso, which is a major grain producer. We still don’t know if the European Union will distinguish biomes within the same State. I say this because Mato Grosso has as much Amazonian Forest as Cerrado. But that doesn’t mean buying from that place will be prohibited. It means that there will be a greater risk and supervision by the European Union will be stricter.

Source: Prodes

Does the producer in risk areas need to prove more forcefully that they are not involved in deforestation?

Yes. Most likely, the producer will need to go through a certification and audit process, something that generates a cost. The entire chain will need to be certified. The norm includes the importation of beef, in which it will be necessary to certify even grain producers. And here comes the difficulty. In relation to higher value-added products such as coffee, where certification is a differential for which consumers are willing to pay, this is not a problem. But this is not the case with commodities such as soybean. And there is logistical complexity as well.

What kind of complexity?

The law says that each agricultural production polygon must comply with environmental rules and must be traceable. And tracking the production and export of commodities is not easy. A ship loaded with soybean brings together the production of hundreds or thousands of farms in various regions of the country. Not to mention the trucks that stop at the silos of various trading companies to be loaded. All that soy is mixed in silos, trucks, trains, and ports. Logistics are like this all over the world.

Soybean shipment at the port of Santos. Publicity photo.

How is this resolved?

The importer will require several measures to manage the risk. The European Union would need to be very careful with the issue that these requirements will generate costs, so products could become expensive in Europe. In meetings with companies, I have asked about the degree of complexity to manage risks. What I’ve heard is the requirements will be met. But there will be costs.

In this scenario, can small and medium producers be excluded from exports?

Yes. Small farmers may be left out of exports to Europe for lack of resources to invest in traceability and more sophisticated certifications. This also applies to small and medium-sized livestock farmers. For this reason, many wonder whether the new European law is actually a form of protectionism. It is a point that is being raised. If the idea is to help control deforestation in the world, excluding producers may not contribute to this.

And there are several causes for deforestation, aren’t there?

Sure. Deforestation doesn’t just happen because of livestock. The data show that vegetation is cut down on public lands also because of mining and illegal cutting and sale of wood. There is criminal activity. Will the new European law put an end to deforestation in the world by relating it only to food production? The European consumer needs to be challenged on this issue. This view that the villain is agribusiness limits our scope to control the problem.

Can the Forestry Code help reduce Brazil’s environmental risk in relation to European law?

You can, but we need to evolve on this point. The Forestry Code is a law that requires preservation of native forest, according to a series of requirements. There is an instrument, the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), within the scope of the Forestry Code, with data on environmental conservation of rural properties. Each State has its CAR platform and many still need to advance further. But this system certainly has the potential to be a great tool for mitigating environmental risk.

Can Brazil intensify trade with other regions of the world because of difficulties in selling to the European Union?

We will never give up Europe as a trading partner. Exporting to Europe is a great business card and the European continent is important for our agribusiness exports. But if there are a lot of obstacles and costs, producers can start selling more to those who facilitate sales. It’s a market issue. Anyway, there are still points of the law to be clarified and Brazil will adapt to the new standards.