Insight Focus

- Corn, soybean and sugar crops could result in logistical problems in Centre-South Brazil.

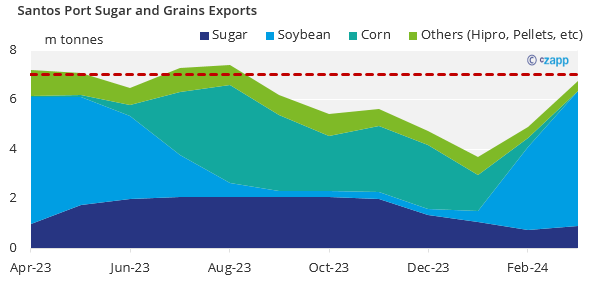

- Export flow for sugar could be limited at 2.6m tonnes per month.

- Rise in truck freights is also expected.

Centre South (CS) Brazil sugar will be the world’s largest supplier of raw sugar in 2023. Any issues with moving sugar to or out of Brazilian ports could have an impact on futures market prices.

As we mentioned in our crop revision for 2023/24, it will not matter if CS Brazil will produce more than 36m tonnes if this sugar cannot be exported.

Port terminals that operate sugar also elevate grains. And due to flow of grains and sugar exports, there is an overlap of both products that can impact not only the loading operation but also the discharge on the terminals.

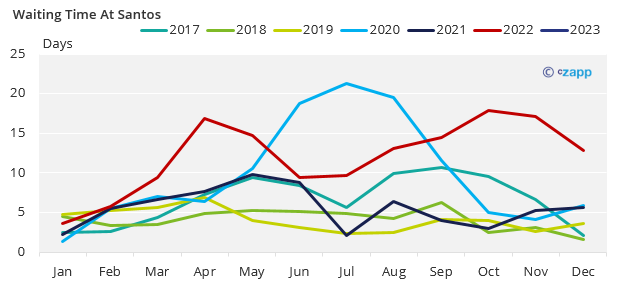

We estimate that monthly sugar exports out of CS Brazil will be limited at around 2.6m tonnes. Any volume nominated above this will roll into next month, possibly creating vessel queues and increasing waiting time to berth – like last year.

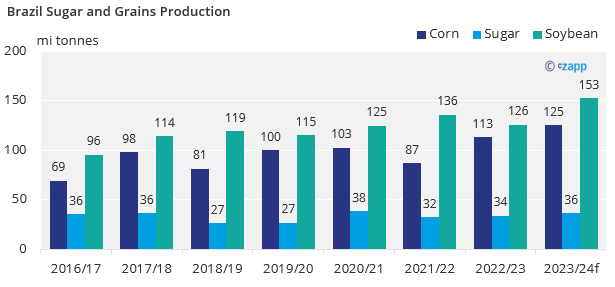

Record Crops

This year, a record crop is expected for corn and soybean, and the second largest for sugar. Corn is expected to grow 10%, soybean 21% and sugar 8%.

Source: Conab, Czapp

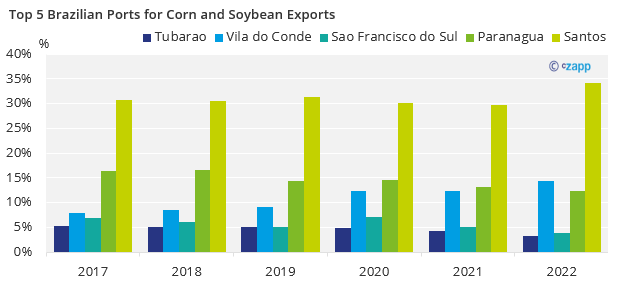

From Where it Flows Out of Brazil

The main corn producer of Brazil is Mato Grosso (MT) state, with 31% of production share followed by Parana (PR) at 13%. However, despite the distance of MT to Santos (located in the state of SP), around 2000 km, over 30% of corn is exported through this port.

The same goes to soybean, with MT producing 33% of total soybean followed by Goiás (GO) at 14%, and over 30% exported via Santos.

Reaching the Port Could Also be an Issue

The bulk of soybean exports occurs between March and June (70%) while the bulk of corn exports between July and November (75%). This coincides with the CS Brazil sugar crop.

The terminals at Santos receive sugar and grains by trains and trucks. The competition then impacts road freight and the allocation of wagons between sugar and grains.

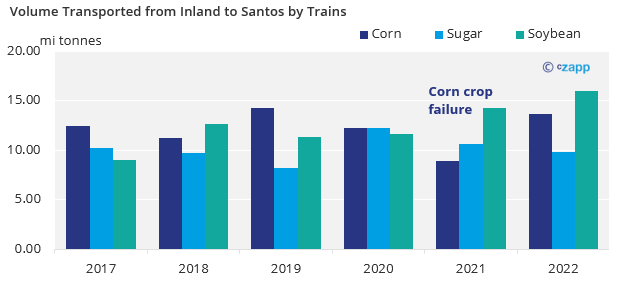

In recent years we have seen an increase of grains being transported by trains to Santos, with sugar share dropping from 30% down to 25% last year.

Less wagons allocated to sugar could delay the flow inland to the port terminals, forcing an alternative being seek like trucks. However, freight prices could rise to a point that it could impact sugar and ethanol parity for frontier states.