Insight Focus

- Promotion of ethanol use could offset rising gasoline prices.

- But faced with food security concerns, governments are rolling back mandates.

- This could lead to further fuel price increases and threaten climate goals, ePure warns.

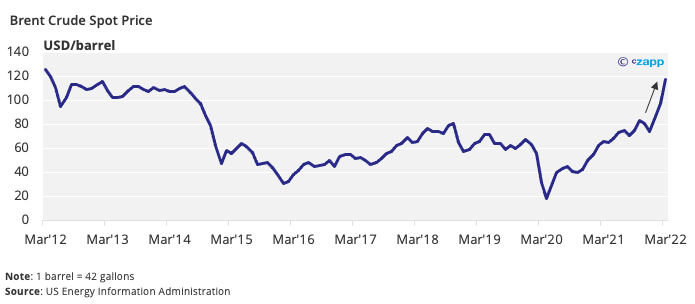

Fuel prices are on the rise and many countries are scrambling to reduce oil and gas reliance on Russia. This means fossil fuel prices will only rise further. Biofuels have long been touted as the cleaner alternative to traditional fuels but a focus on food shortages is now jeopardising progress.

Rising Fuel Prices Creates Race for Alternatives

Fuel prices are rising fast due to a perfect storm creating lower supply and higher demand. The European Union is preparing a sixth round of financial sanctions over Russia’s war in Ukraine, which could involve reducing or ending Russian crude and oil-product imports. This would mean it would have to seek up to 2.85m barrels a day of oil from othercountries, which would likely push prices even higher.

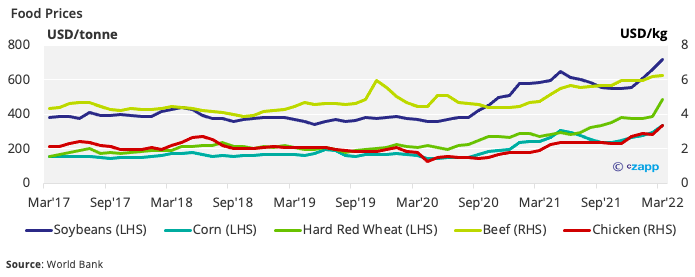

The world is also grappling with a rising cost of living amid rapidly increasing inflation rates. As food and energy prices rise, tensions are hitting boiling point, particularly in countries such as Sudan that were already suffering from lack of food security. Governments are now looking for solutions to alleviate pressure on the public.

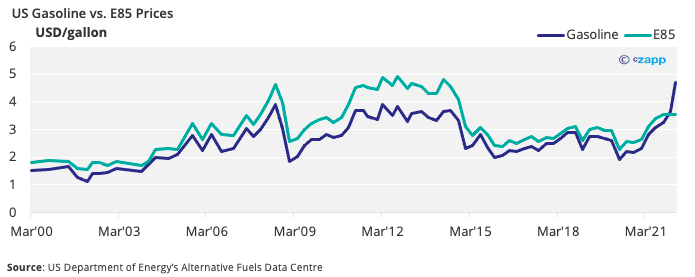

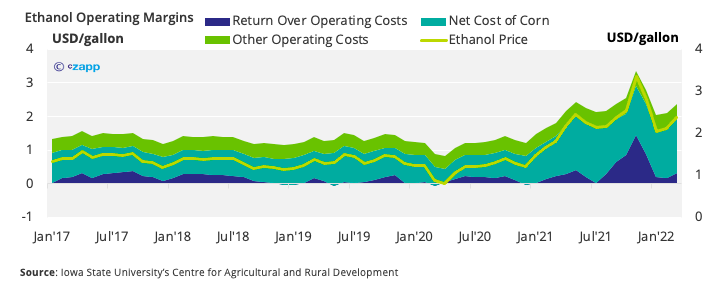

One way consumer pressure can be alleviated is by turning to alternative fuels, such as ethanol. Due to crude price rises, the average US retail price of E85 (a blend of 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline) fell below that of gasoline for the first time in March.

Countries Meet Hurdles in Push to Strengthen Production

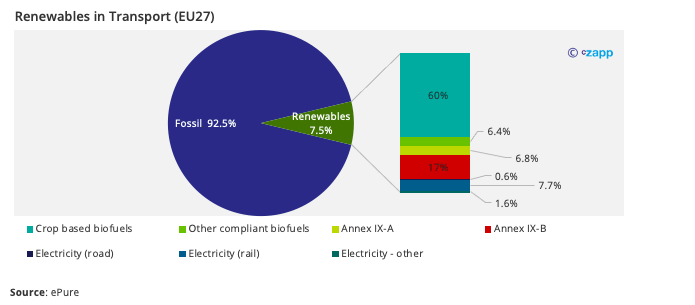

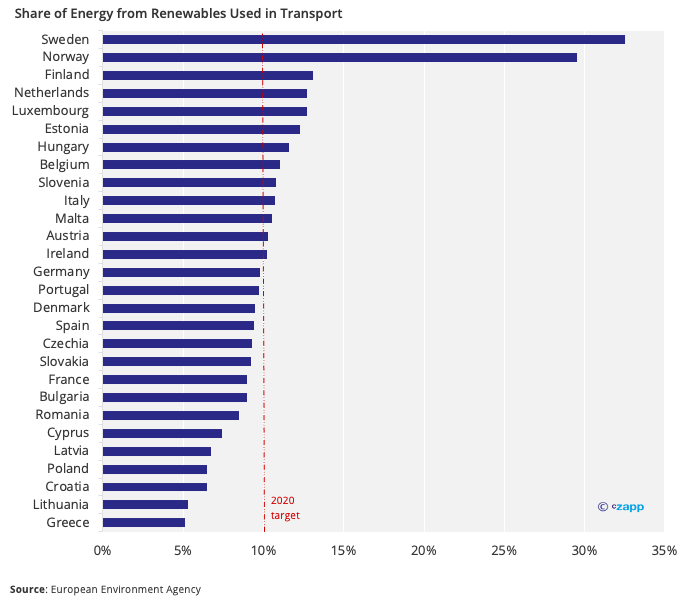

But the question is: Are crude oil prices high enough to warrant widescale ethanol use? Although there’s been a push to boost ethanol uptake in the past few years, penetration remains weak. In 2020, 92.5% of transport energy came from fossil fuels. Crop-based fuels accounted for 60% of the remaining 7.5%, according to Eurostat.

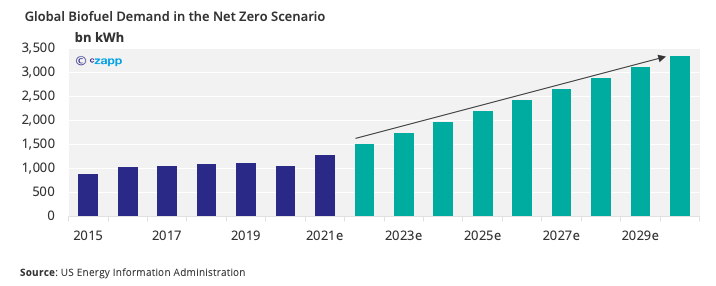

The US Energy Information Agency estimates that global transport biofuel production was the equivalent of 2.8m barrels per day of crude in 2019. While this may seem like a lot, global production of motor gasoline reached close to 10m barrels per day. This suggests that the world needs three and a half times more ethanol capacity if it is to replace gasoline.

Cars need to be enabled to run on ethanol. Currently, only 60-70 million vehicles in the global fleet are flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs) and these are mainly concentrated in Brazil, the US and Canada.

But cars can also be retrofitted relatively easily and cheaply. Devices can be purchased for around USD 500, which are fitted to the car to enable it to run on E85.

But complete replacement of gasoline is also a long way off. E85 blends, while high in ethanol content, still require gasoline in some form. A complete redesign of the vehicles would be needed to make E100 fuel usable.

And while the US’ E85 prices dropped below those of gasoline last month, it remains expensive to bring online production capacity. Depending on location, production capacity and existing infrastructure, a new plant can cost anywhere from tens to several hundreds of millions of dollars to set up. It can also take several years to receive relevant approvals, permits and pass the design stage – meaning new capacity cannot be quickly brought online.

Ethanol Mandates Face Scrutiny

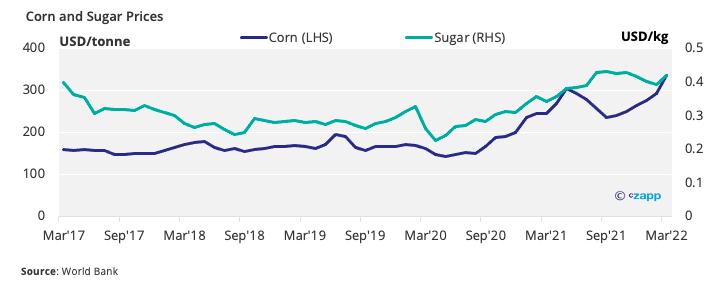

With high grains prices and high crude prices, there’s also conflict between ethanol mandates and food security. In a communication released in March on safeguarding food security, the European Commission (EC) made it clear that food was a priority over biofuels.

The EC said it supported members in reducing biofuels blending in situations that could free up land for food and feed commodities. In fact, the EC explicitly stated that “in this crisis, we must avoid that use of food and feed crops as feedstock for biofuel increases.” It instead called on members to focus on investments in sustainable biomass sources such as agricultural and aquacultural waste and residues.

Finland has already announced that it’ll reduce its biofuel mandate and Sweden has proposed a freeze of its 2023 mandate at 2022 levels. Croatia also withdrew penalties for blenders that miss targets and Norway also reduced its mandate for road fuels this March to 17% from 25%. Biofuel use in transportation in the Nordics is among the highest levels globally.

European ethanol association, ePure, criticised the EC’s move, warning it could “seriously undermine Green Deal ambitions, jeopardise the internal market and food security, and hamper efforts to ensure Europe’s energy independence.”

And in Malaysia, the Malaysian Biodiesel Association (MBA) had a similar message for the government amid calls from the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) to slow the use of edible palm oil as biofuel in an effort to guarantee supply. In Malaysia, it is compulsory for biodiesel to contain at least 20% palm oil.

India, on the other hand, is focusing increasingly on ethanol production as a way to redirect its 35m tonne per year sucrose production and reduce its surplus. An increasing amount will be diverted to ethanol production, finally reaching 6m tonnes by 2025 as it targets a 20% ethanol blending mandate by 2025.

Brazil – a leader in ethanol due to its vast sugarcane cultivation – launched RenovaBio in 2019, which is expected to raise ethanol demand by 25% to 50% by 2030.

Meanwhile, the US is wrestling over the decision to address fuel prices or food prices. In March, Reuters reported that President Joe Biden was also mulling an ethanol blending waiver to ease food inflation. However, the government is now allowing for expanded E15 blending over the summer to tackle rising fuel costs. Rising corn prices could negate any financial savings from this initiative though.

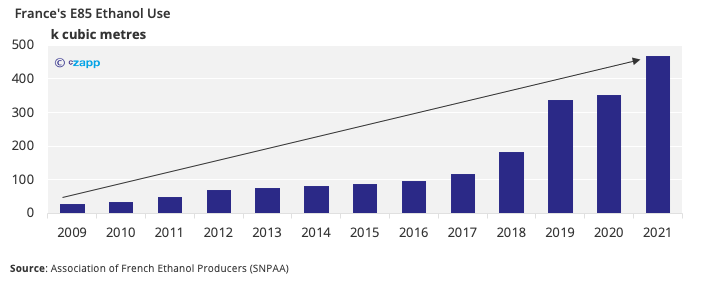

In France, E85 use is relatively widespread and is growing. As of February 2022, 2,786 of France’s service stations sell E85, up over 150% since 2019. Now, about 30% of gas stations in the country stock E85.

But ethanol in France is subject to a lower tax than traditional gasoline, which effectively acts as a subsidy. The average price for E85 at French petrol stations on the 25th March was 1.02 USD/litre compared with 2.12 USD/litre for unleaded gasoline.

Rolling Back of Mandates Jeopardises Clean Energy Goals

The main reason many countries have promoted ethanol until now has been to meet environmental commitments, given that ethanol is a cleaner fuel than gasoline.

In Europe, the Fit for 55 policy aims to generate 13% less greenhouse gas emissions from transport by 2030, which means increased renewables’ share in transport fuels to 28%. Canada and the US also have similar plans to reduce greenhouse gas intensity from transport fuels – with ethanol playing a key role in attaining this goal.

According to ePure, food security goals can be achieved without compromising on clean energy goals. “Supporting the reduction of biofuels blending sends the wrong signal, at a moment when European agriculture is being called upon to produce more while continuing to make progress on sustainability,” it says.

If the world wants to meet its climate goals, solutions such as biofuels are essential.

The Food vs. Fuel Argument

It can be argued that there’s a conflict between food supply and ethanol supply. Amid global food price rises and concerns over supply of agricultural staples from Russia and Ukraine, it’s not surprising that the priority of many countries has been to safeguard food supply at all costs.

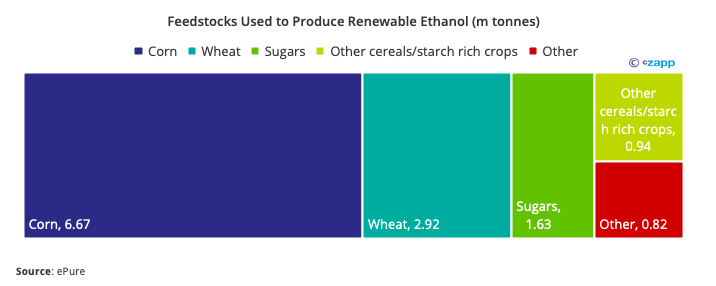

On the surface, it seems ethanol could pose a serious threat to food security, given that the most common feedstocks are corn, wheat and cane.

However, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission had prioritised the phasing out of biofuels from edible crops. It confirmed in its 2022 short-term outlook that, despite the war in Ukraine, “the EU is largely self-sufficient for food, with a massive agri-food trade surplus.”

Moreover, only around 7% of global crops are currently used for biofuels production and this mainly takes place in those countries that have a surplus of feedstock. The alternative to producing ethanol would be selling the primary agricultural products on the global market, weighing down the price of these commodities.

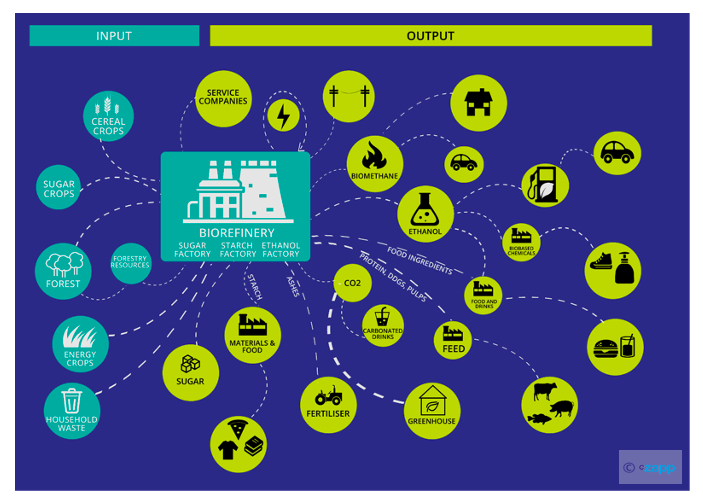

ePure also argues that the ethanol and food supply chains work in sync, creating uses for otherwise low-value outputs such as gluten, vinasses and captured CO2 to be used in cold storage.

“EU biorefineries play a major strategic role in securing food and high-protein feed supply and helping consumers to access affordable transport modes, thus reducing EU energy dependency as well as GHG emissions in the transport sector,” says the organisation.

Concluding Thoughts

To reduce dependence on Russia and combat the rising cost of fuel, alternative options are needed. But increasing concerns over food security are causing many countries to place less importance on biofuels mandates to ensure critical food security.

However, there’s a delicate balance to be maintained between ethanol mandates and ensuring food security. In many cases, there’s no need to compromise on environmental goals to ensure food supply. In fact, the rolling back of mandates could exacerbate the cost-of-living crisis by driving fuel prices up further.

According to ePure, “there is no problem of food supply in Europe, but rather of food affordability.” The organisation adds that the EU should avoid encouraging actions that create additional market instability.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Why the Chinese Pig Herd Matters Globally

Food Security Trumps Standards as Supply Pressure Mounts

Explainers That May Be of Interest …