Insight Focus

- Onshoring initiatives were launched last year in response to supply chain bottlenecks.

- While this alleviates logistics issues, there are trade-offs to be made.

- Other options like diversification, nearshoring and overstocking may be better for manufacturers.

There was a lot of rhetoric about onshoring supply chains last year as globalisation came under scrutiny. COVID-19 made manufacturers and distributors take a closer look at their supply chains, but almost two years on, onshoring activity has been limited. Manufacturers are more aware that they need to consider not only primary costs but also risk, infrastructure and reliability, and there are other options to consider.

Supply Chain Issues Spark Onshoring Talk

Since 2020, global supply chains have been an inadvertent victim of COVID-19. Delays, price rises, and unavailability of freight have caused companies to re-examine how long their supply chains had become.

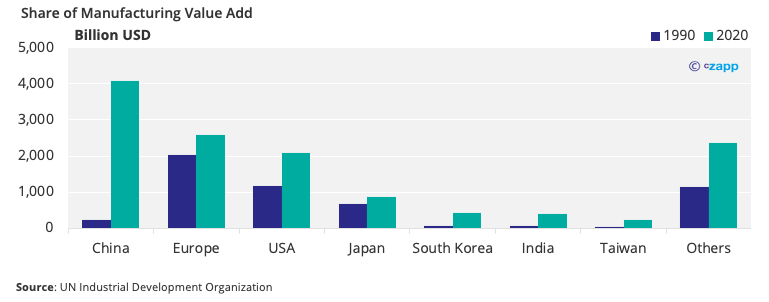

In the past 30 years, the lion’s share of global manufacturing activity has gradually moved away from the USA and Europe to China and South Asia.

This proved problematic when COVID closed supply chains down, leaving most of the world vulnerable due to its dependence on Chinese manufacturing capability. The situation prompted countries previously known for their manufacturing strengths, such as the USA, to prioritise domestic manufacturing for certain key industries.

US President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 14017, also known as America’s Supply Chains, in February 2021 to identify points of failure in the country’s supply of basic goods. A final report was submitted by the Secretary of Agriculture this February.

At the same time, the European Parliament’s Committee on International Trade commissioned a study on the potential for reshoring production back to the EU. According to the report, reshoring can be “promoted directly by sector-specific policies and indirectly by horizontal policies.” These horizontal policies include carbon taxes and preferential tariffs.

There are limited opportunities to onshore agricultural supply chains, given that certain crops only grow in certain climates. There’s also fragmentation in the supply of farming inputs, including machinery, seeds and fertilisers.

Secondary Costs Could Offset Disadvantages

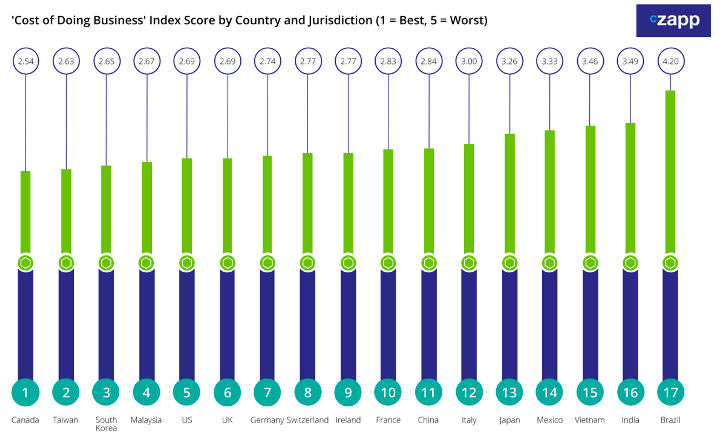

One of the main attractions of offshoring is in reducing costs. With factories overseas, manufacturers can outsource labour, infrastructure, and operational costs. In a recent KPMG ranking on the costs of doing business, the top five countries in terms of primary costs were Malaysia, China, Mexico, Vietnam and India.

Increasing direct production costs by onshoring will likely increase the final price of consumer and agricultural goods, and governments are unlikely to consider hiking the price of goods during a time when inflationary pressure is weighing on households.

But there are also secondary costs involved in manufacturing, including the quality of labour, ease of doing business, quality of infrastructure and the level of in-country risk. When these costs are taken into account, the KPMG ranking changes dramatically.

Until now, cost has been king in manufacturing activity but after the pandemic, companies have started to recognise that resilience in supply chains can be much more important to keep costs down in the long term. This can mean moving operations to countries with higher production costs in exchange for a lower level of risk.

Emissions Considerations Complicate Onshoring Plans

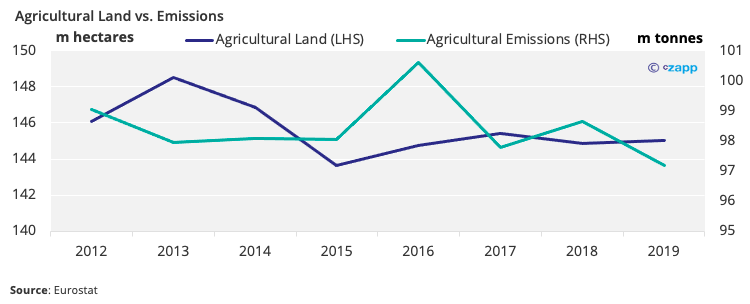

Until now, an appealing aspect of offshoring has been lowering emissions due to less industrial production. However, the EU has developed a rigorous Farm to Fork policy that outlines a desire to reduce the impact of primary agricultural production on the climate.

In Europe, there has been some success in reducing agricultural emissions over the years. Between 2012 and 2019, agricultural emissions went from 99m tonnes to about 97m tonnes of CO2 equivalent. But the size of the agricultural land in the EU has also decreased from 146m hectares to 145m hectares during the same period.

Across the EU, industrial gas consumption has declined by 20% since 2000, and now, the largest use of gas is the residential sector and power generation. This is primarily because the EU has transitioned from being a manufacturing economy to a services-based economy.

The EU has pledged to cut carbon emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (from a 1990 baseline) and to become climate neutral by 2050. Onshoring more manufacturing capability will likely increase emissions and set these goals back, though.

The EU is also in the process of implementing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) for heavily emitting industries. This would mean products manufactured abroad using a process that emits high amounts of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide would be subject to an additional import tax to offset the emissions.

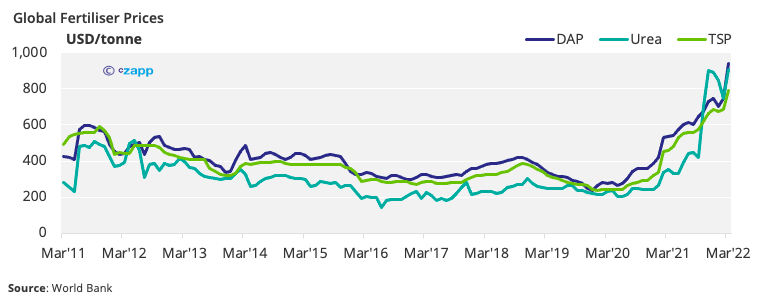

The current proposal does not apply to foodstuffs and agricultural goods, but it does apply to fertiliser due to its energy intensive manufacturing process. These additional costs for food producers would likely be passed on throughout the food chain, making food manufacturing in the EU more expensive, especially given the current rise in fertiliser prices.

Onshoring food production would also require widescale changes of land use – something that’s widely recognised as creating the most emissions in the agricultural process.

What Alternatives Are There?

If the last few years has taught us anything, it’s that supply chains need careful examination. But if onshoring is not the answer, what is? Well, there are a few alternatives.

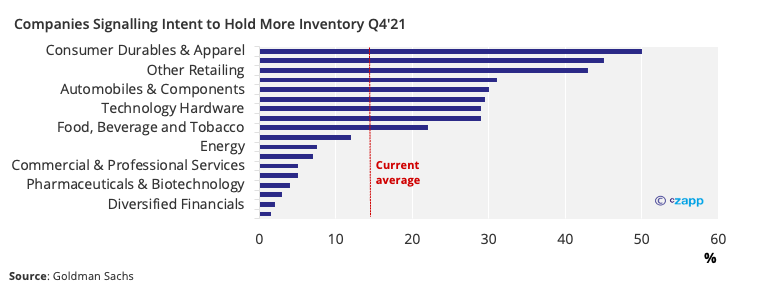

One is overstocking. Rather than onshoring, companies are now holding more stock at domestic facilities. This could spell the end of “just in time” and cost more for warehousing but alleviates the bottlenecks caused by freight disruptions. This strategy works better for durable goods, though, and not necessarily perishables.

But many food and staples retailers have signalled their intent to hold more stocks, according to Goldman Sachs research.

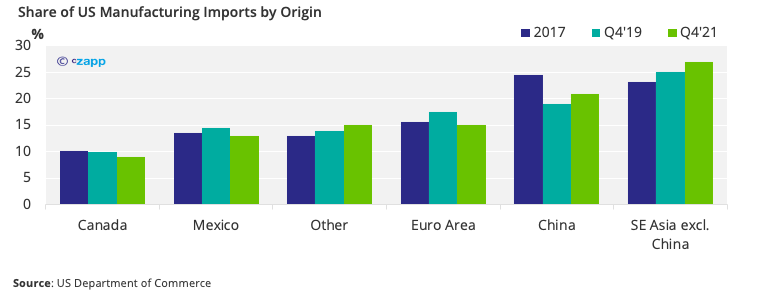

Another response by manufacturers has been the diversification of supplier networks. Since 2017, US manufacturing imports have moved away from China and across the rest of Asia – likely in response to the tariff war and China-US tensions, which escalated during Donald Trump’s presidency and are still high.

However, there’s concentration in the agricultural food chain, which has been highlighted most recently with the Russia-Ukraine war. For example, 30% of the world’s grains come from Russia and Ukraine, and Russia also produces about 8% of global fertilisers.

Agricultural production requires vast swathes of arable land – a characteristic that is limited to certain countries. Predictably, this means China, India, the USA and Brazil are some of the world’s largest producers of primary agricultural products.

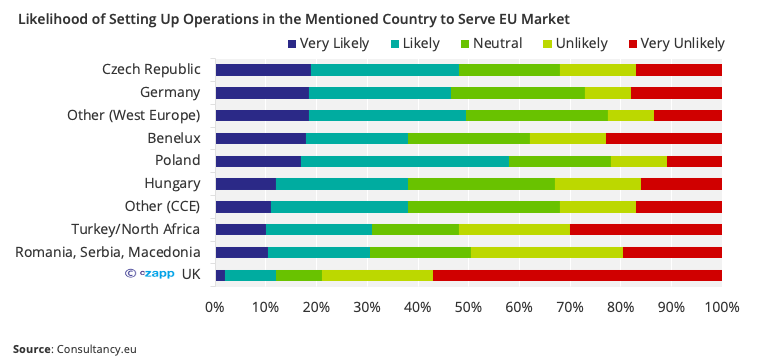

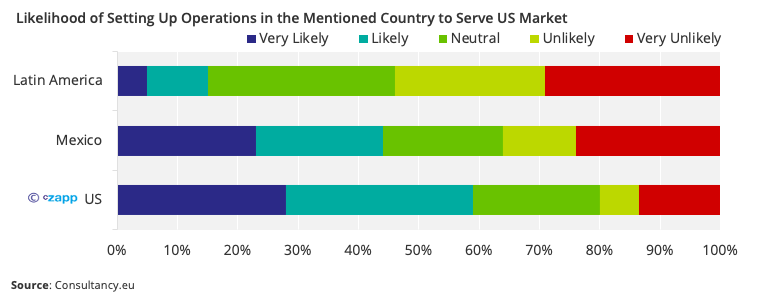

The best of both worlds seems to come from nearshoring. Companies can move production and manufacturing lines closer while keeping costs low.

For Western European companies, this often means moving production to Central and Eastern Europe and Turkey.

For the US and Canada, manufacturing operations can be nearshored to Mexico, Central and South America.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite talk of onshoring supply chains in recent years, there has been little progress. There’s almost always a trade-off for countries and companies investigating whether to do so, and often they revolve around sustainability and cost.

But that doesn’t mean countries need to compromise on food security. This may instead come more in the form of strategic alliances, diversification of supply, nearshoring, and overstocking – although the latter option is more difficult for fresh produce.

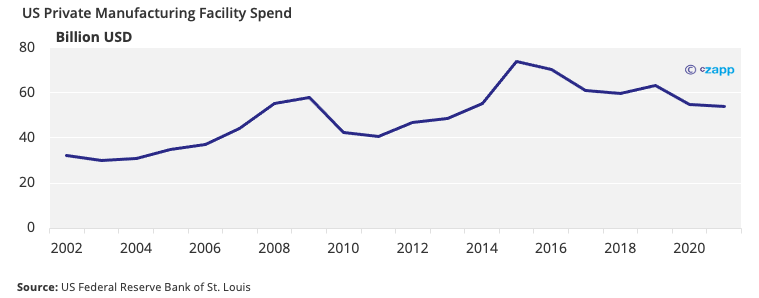

As a result, US private spending on manufacturing facilities has plateaued, although a report from Goldman Sachs points out that “job advertisements suggest that the share of manufacturing activity US companies plan to do domestically rather than abroad has at least stopped falling.”

But one thing that’s for sure is that the era of low-cost offshoring is over. While primary costs may be lower in certain countries, companies are now realising that there’s a trade-off in terms of risk, reliability and infrastructure – and that often comes with a hidden price tag.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Russian Food Self-Sufficiency: Reality or a Potemkin Village?