Insight Focus

- Russia is the world’s fourth-largest fertiliser producer.

- Sanctions should create shortages and further price rises.

- Farmers tell Czapp what they’re doing to mitigate the impact.

The effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine are being felt by the global agricultural market. Russia’s strength as a fertiliser exporter, coupled with sanctions, means farmers need to get inventive about how they nourish their crops. Czapp spoke to farmers in the UK, Thailand, and Belize to find out how they’re addressing these issues.

Sanctions Limit Russian Product Purchases

Russia is a major fertiliser producer, accounting for almost 9% of global supply in 2019 when it churned out 10.9m tonnes of nitrogen fertiliser.

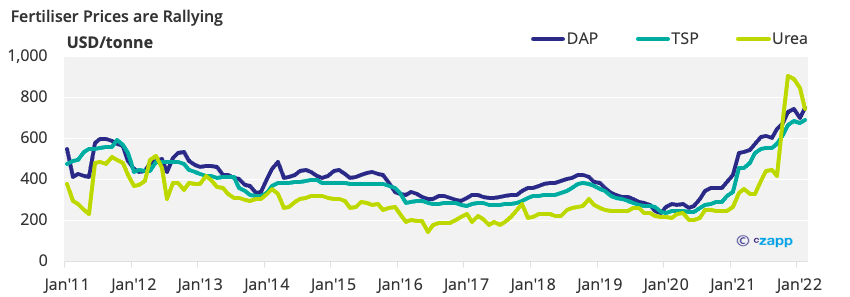

The recent energy rally has driven up fertiliser prices, with urea reaching an average of 744.20 USD/tonne in February 2022, the highest it’s been since 2008.

Many countries have imposed sanctions on Russia too following its invasion of Ukraine. These include financial sanctions and hampering purchases of Russia’s key exports. In the face of more limited supply, fertiliser prices are at risk of increasing even further this year.

Farmers Feel the Pressure

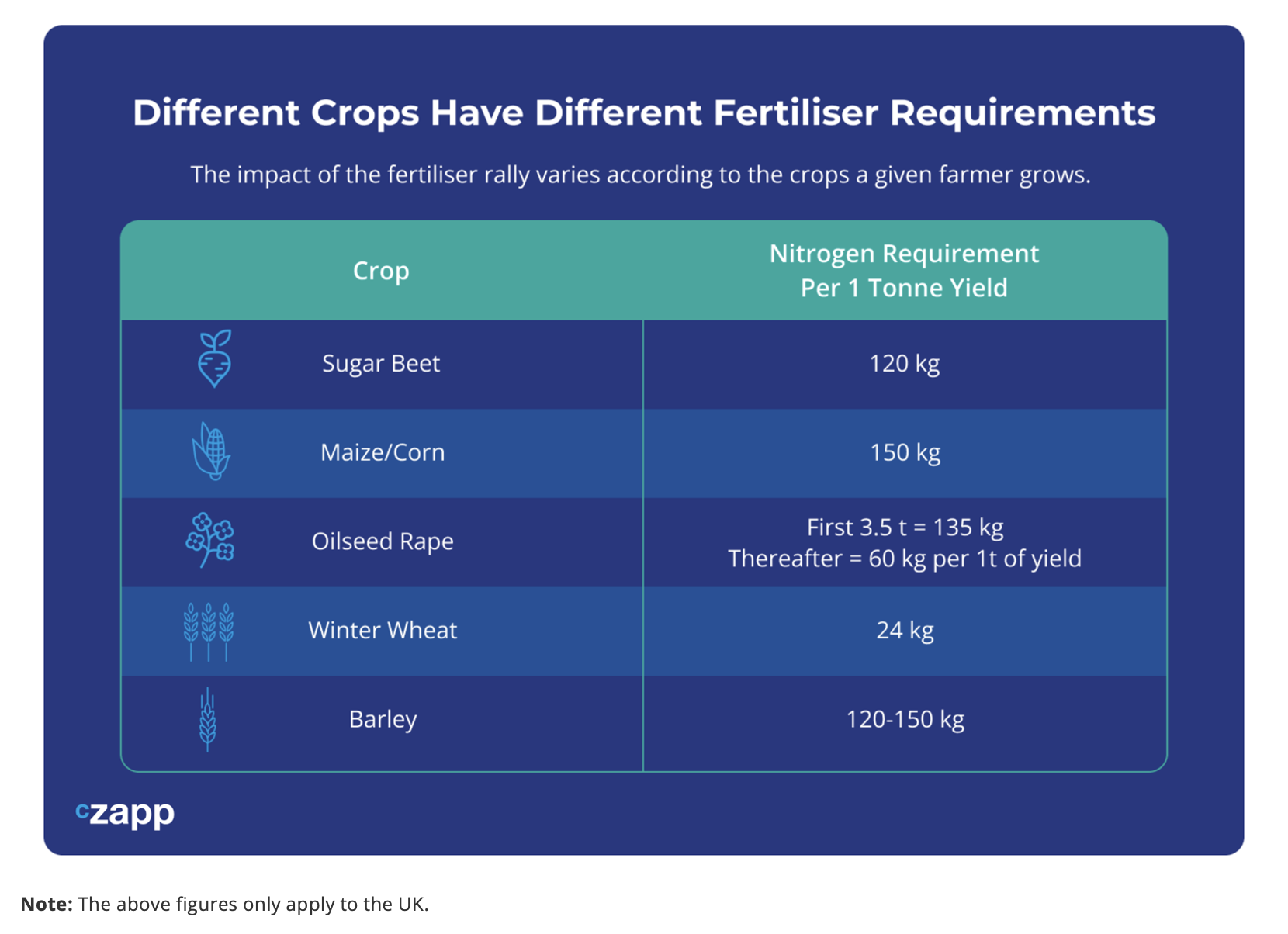

Different crops have different fertiliser requirements, so the impact of the fertiliser rally varies according to what a given farmer grows.

The main inorganic fertilisers provide the nutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Nitrogen is considered the most important and can be derived from the soil, air, and manure. 30kg of nitrogen is typically available from the soil, though this is highly dependent on its quality and the carryover from the previous crop. The remainder comes from fertilisers and manure.

There are limits to the amount of manure that can be applied, though. In the UK, there are several regulations surrounding application of manure to wheat crops, meaning it’s generally not used. As a result, fertilisers are required in almost every circumstance.

In Thailand, farmers must apply fertilisers to sugarcane twice per crop, only conducting three applications if it’s particularly wet. An additional application in poor rains generates very little benefit in terms of yields.

How Can Farmers Protect Their Margins?

There’s no one size fits all solution to the problem.

In Thailand, fertiliser application is dictated by budget. Farmers that apply three applications will only really do so if they’re offered pre-payment from the mills. Farmers also tend to switch to a lower grade fertiliser, or reduce the amount applied, to combat price fluctuations. These moves often reduce yields.

“The farmers understand that the more fertiliser they can apply, the more agricultural yield they can achieve,” a farmer in Thailand told Czapp.

In the UK, farmers are now being advised to trim fertiliser application to wheat and oilseed rape by about 50kg per tonne of yield, reduce fertiliser for sugar beet crops by about 30kg per tonne and to leave barley unchanged. However, farmers feel this will undoubtedly weaken yields, particularly in the case of wheat and oilseed rape.

Likewise, in Belize, farmers are reducing the amount of fertiliser applied by 25%, adding compost to the mix instead. This shouldn’t impact yields, but in Guatemala, the chosen method of substituting fertiliser for a cheaper version (vinasse) will likely reduce yields by 10-15%.

It’s also worth noting that fertiliser requirements can drastically vary, even for the same crop and when strictly following guidelines. “There is a margin of error of 50kg,” one UK farmer told Czapp. “At the extreme, this could lead to a yield variation of as much as 4 tonnes/hectare in the case of wheat.”

Wheat Prices Alleviate Some Tension

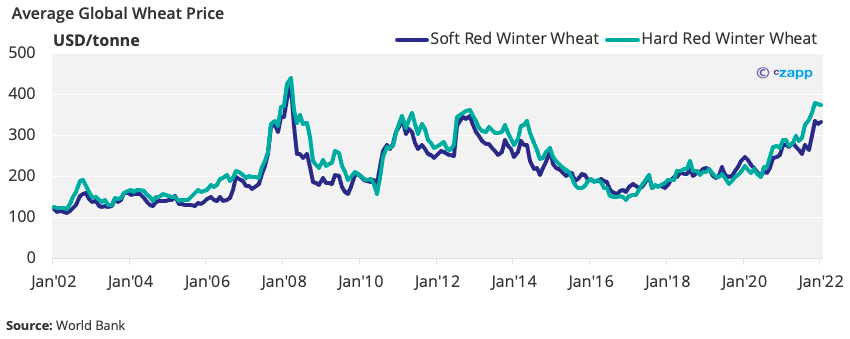

Wider commodity prices are rising, and wheat is alleviating a little pressure, with prices now at their highest level since 2008.

So, with global agricultural commodity prices rallying alongside energy, farmers’ margins are not quite as squeezed as they’d have been had food prices remained stable.

A switch from fertiliser intensive crops is also being seen. Crops such as beans and peas require little to no fertiliser, and some farmers prefer to plant these rather than those that require high levels of nitrogen fertiliser. Both are also relatively hardy and can generally survive in sub-zero temperatures, although they may suffer some damage.

However, this option may not be available to all farmers. Some follow strict crop rotations, while others have infrastructural limitations to switching crops. This is the case for farmers in cooperatives or in cases where the processing mills or factories own the land. Costs of production can also vary depending on a number of factors, so in some cases, switching to beans or peas is not economically viable.

Concluding Thoughts

- Farmers are combatting fertiliser price rises by altering the amount they apply to each crop.

- However, there’s a consensus that this will negatively impact yields.

- The light at the end of the tunnel is that rise rising agricultural commodity prices mean farmers can sell end products for a larger profit.

- Still, some farmers are switching to crops that have little to no fertiliser requirements, such as beans and peas.

- This has the potential to take cultivation area away from other food staples.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Black Sea Sugar Freight Suffers Little War Disruption

Is ‘Fortress Russia’ Self-Sufficient in Sugar?

Explainers That May Be of Interest…