Insight Focus

- Widespread potato shortages are causing chaos for multinationals.

- These shortages are a symptom of extended, inefficient supply chains.

- Producers may need to reshape supply chains to prevent future volatility.

Potatoes are an agricultural staple that are normally easily obtained. Recently, though, they’ve hit the headlines as shortages have prompted rationing in Asia. But rather than a potato shortage, the problem seems to the fragmented global supply chain that’s now under pressure. This is a problem familiar to the whole of the food industry.

Everyone’s Talking About Potato Shortages

Potato shortages are global news.

At the end of January, McDonald’s in Indonesia and Malaysia announced that it’d temporarily halt the sale of large fries. In Japan, the chain has been forced to ration fries over the past month and fellow fast-food chain, Mos Burger, suspended fry sales.

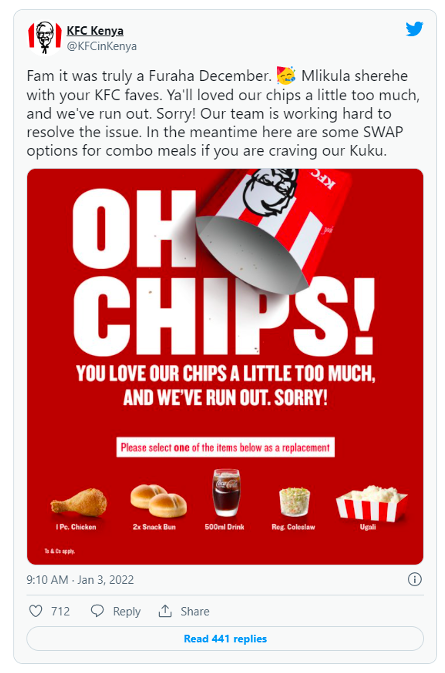

It’s not just Asia that’s feeling the impact, though. In Kenya, KFC ran out of fries in January and South Africa’s favourite crisp manufacturer, Simba, announced that it was experiencing disruption two months ago.

Across the past two years, a volatile container market has disrupted food supply chains, with millions of tonnes of produce left to spoil due to lack of workforce to harvest them or logistics providers to transport them. Potatoes were no exception, and the shockwaves are hitting in 2022.

At the end of 2021, global trade was seemingly stabilising as freight started to fall again. However, both Omicron and rising energy prices mean the cost of container freight has risen again in 2022.

Food shortages have been blamed on COVID-induced disruption, but the truth is that the blame may not lie solely on its shoulders. Although COVID has likely exacerbated difficulties, a perfect storm has formed to restrict potato supply on the world market.

The Root of the Issue

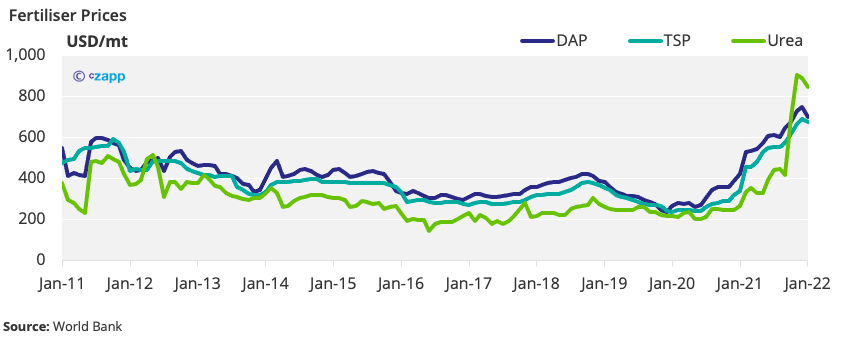

First of all, input costs are rising. Fertiliser prices are also pushing up the potato price. We wrote about the implications of a higher fertilizer price on European farming and what the industry can do to combat the costs.

Problems with the weather and pests have dealt a blow to the industry this year too. Right now, in Puerto Rico, there are gaps on the supermarket shelves where once there were potatoes, 80% of which usually would come from a small Canadian island called Prince Edward Island. Because of a potato wart ou break scare, these shipments have been temporarily stopped. The PEI potato issue is adding pressure to an already precarious potato situation in the US.

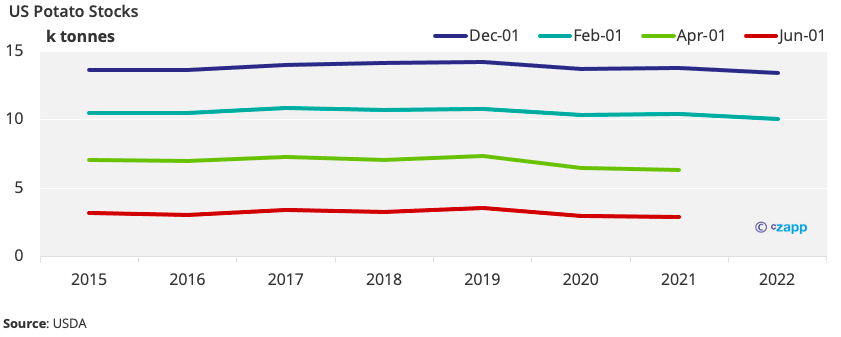

In the past year, US potato stocks have declined to their lowest since 2015. As of February, 11.1k tonnes of stocks are held, down 385k tonnes year-on-year.

Chipping Away at the Supply Chain

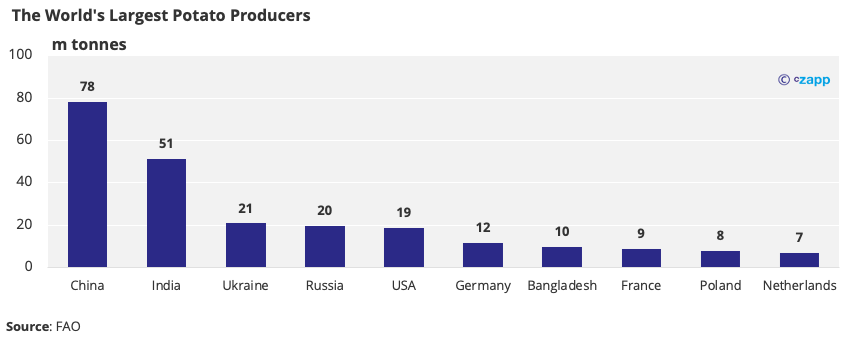

The potato growing industry is dominated by a few large players, with the top 10 producers growing 65% of the world’s potatoes. This means that if a crop is reduced by pests or poor weather, there are ramifications for the whole supply chain.

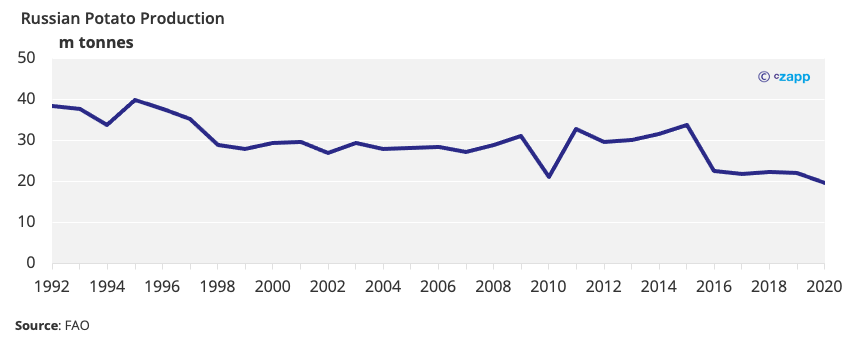

Right now, this is what is happening in Russia. Russian production has been steadily dropping since the 1990s. In 2021, poor weather meant the harvest was not as large as expected, placing additional strain on supply.

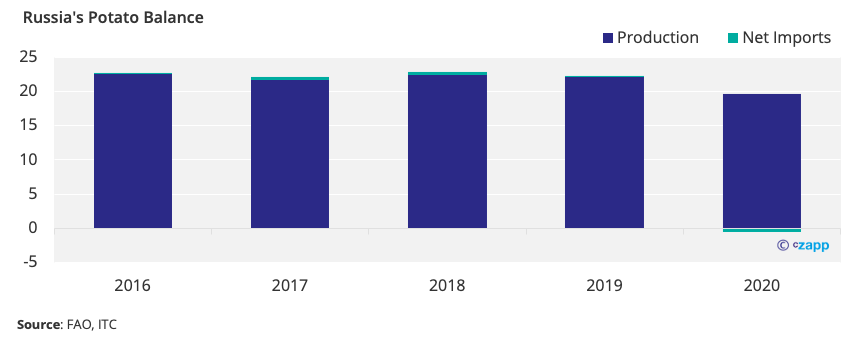

As production has decreased, imports have dropped. But in 2020, Russia became a net exporter, meaning apparent consumption dropped to 19m tonnes in 2019 from about 22m tonnes in 2016.

The fragmentation of the potato supply chain is exacerbated by the growing process. Seed potatoes are needed to grow potatoes. The problem is that the largest producers of seed potatoes aren’t necessarily the largest potato producers. Sourcing the seed potatoes therefore adds an extra layer of complexity to the supply chain.

A Glimmer of Hope for the Potato Market

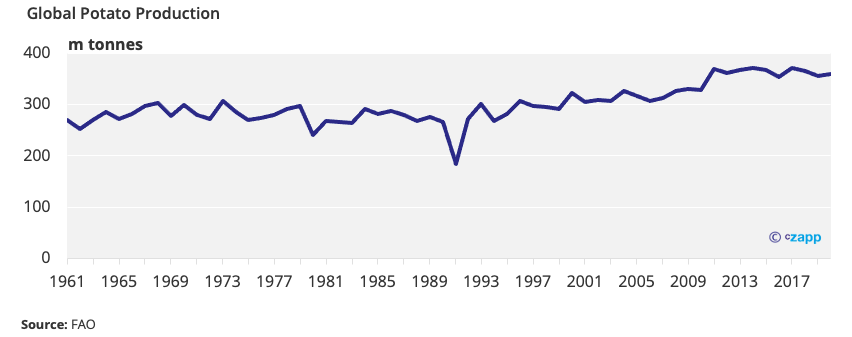

Globally, there’s no potato supply shortage. According to the data, potato production is relatively stable, even rising slightly over the last few years.

The problem is that the potato industry is fragmented. While production in certain regions remained stable, or even increased, the drop caused by pest and blight in other regions was brought to the forefront when global trade was interrupted, and they were unable to plug the gaps.

There are enough potatoes, but because of the complexity and fragmentation of the supply chains globally, there’s not necessarily enough in the right places at the right time. So, what can be done?

Well, some of the issues aren’t due to the supply chain, but to corporate policies. For example, in the case of the KFC fry shortage in South Africa, the same problems were not felt by Burger King South Africa. Why? Because Burger King was able to shift procurement to local producers, but KFC could not, due to “global quality standards.” Now, KFC Kenya has pledged to its customers that it’ll secure domestic potato supply.

Another way supply chain bottlenecks can be alleviated is by increasing production capacity. Last summer, a research team at the Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, under the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), developed a new genome that can significantly increase yields, in turn reducing inputs and costs.

It’s also helpful that in some locations, especially the Americas and Europe, COVID restrictions are coming to an end. In the UK, those testing positive will no longer have to self-isolate, which could solve some of the personnel issues experienced in the past few years. However, other countries have not yet reached this position, and bottlenecks won’t likely ease until there’s a global loosening of restrictions. China, for example, is still pursuing a “zero COVID” policy, which will to involve strict restrictions for those testing positive.

A Supply Chain Reshape

Rising input costs are bound to exacerbate the potato situation given the elongated supply chain. Higher freight and fertiliser costs will push potato prices higher, although this may compel producers to bring more capacity online. Given that potatoes take between 10 weeks and 20 weeks to grow from planting, it’s unlikely that immediate gaps in supply will be plugged.

But the real issue with the potato saga is not a lack of supply, rather a lack of supply in the correct places. The supply chain’s reliance on logistics and extended supply lines means these issues will likely continue until global trade normalises again and production stabilises in Russia.

All this signals that change may be necessary. If they learn lessons from the potato saga, countries and companies may need to look to shorten and simplify supply chains, reducing dependence on imports and sourcing local produce. There have already been calls for Russia to invest significantly in domestic seed development to enable Russia to self-supply seed potatoes again.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Lessons in Food Security from Asia’s Most Densely Populated Nation

Should CS Brazil Fear China’s Drive for Sugar Self-Sufficiency?

Market View: What the Ukraine Crisis Means for Sugar

Explainers That May Be of Interest…