Insight Focus

- The EU wants to half retail and consumer food waste by 2030.

- Most food waste happens higher up the supply chain.

- Waste emissions put at 16-22% of EU total for food consumed.

The European Union’s Farm to Fork strategy was launched in May 2020 under the framework of the European Green Deal.

The strategy sets out several pledges and targets for the EU to reach by 2030 with the goal of creating a more sustainable, environmentally friendly food value chain.

While some proposals are more specific than others, the Farm to Fork strategy is an ambitious plan but it has invited some criticism. Over this eight-part series, we aim to provide you with a greater understanding of the policy’s implications and how it might affect your day-to-day business.

The EU Wants to Reduce Food Waste

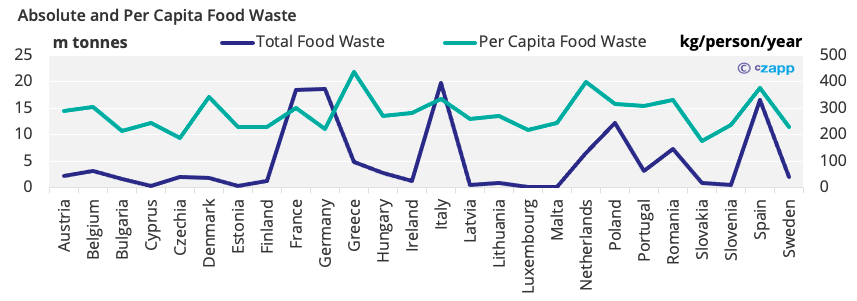

According to the European Commission (EC), the EU wastes around 20% of the total food it produces. This equates to around, 129mmt/year, 278 kg/person/year…or 993 Big Macs.

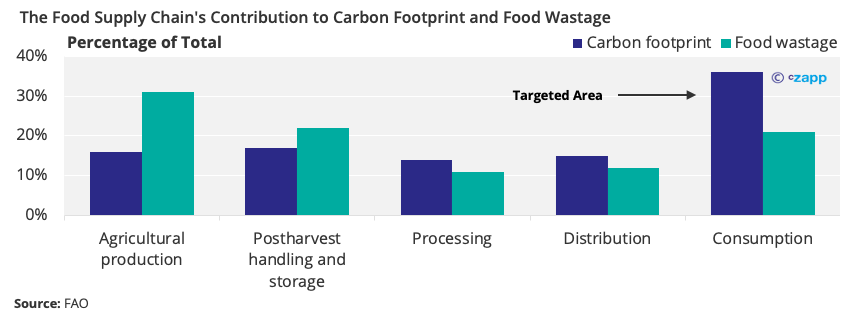

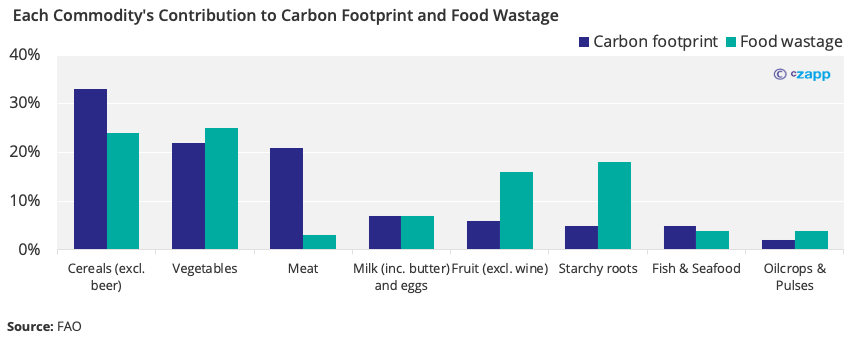

Therefore, through its Farm to Fork strategy, the EC hopes to reduce food waste at the post-production stages by at least half, given the high carbon footprint.

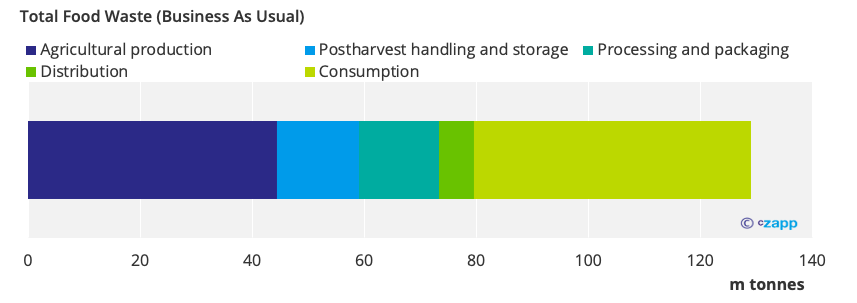

However, the FAO claims that over half of all food waste occurs during agricultural production, post-harvest handling and storage, with just 21% occurring at the consumption stage.

Are the EU’s Efforts Misplaced?

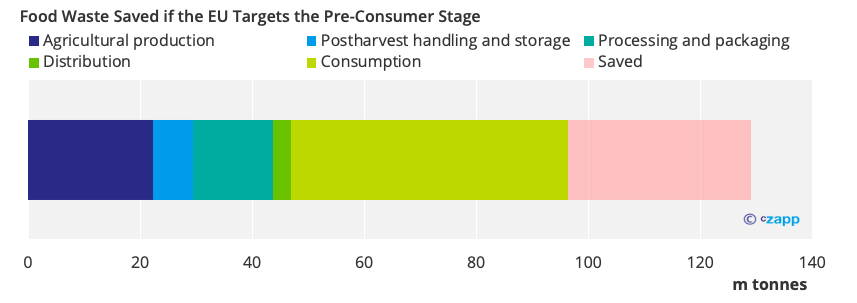

The EU’s efforts to tackle post-production food waste could help save about 25m tonnes each year, if successful, but as the largest proportion of waste occurs before it even gets to the shelves, it seems the EU is missing the opportunity to address the key cause of food waste.

In a business-as-usual scenario, about 49m tonnes of food waste is generated at the consumer stage each year. But this means that about 80m tonnes is generated before this stage.

So, the European Commission focused on pre-consumer food waste, a further 41m tonnes could be saved.

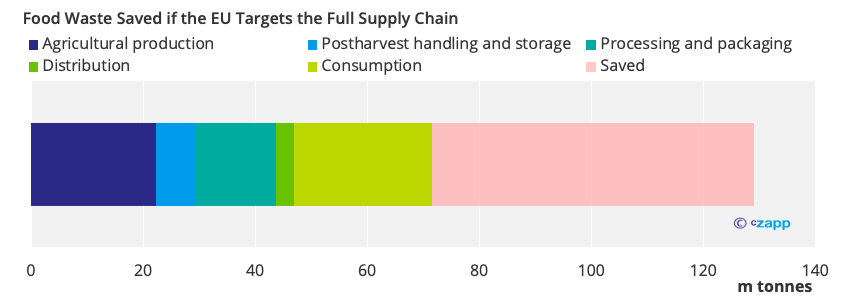

And when targeting both consumer and pre-consumer losses, about 57m tonnes could be saved.

This seems to be the next step for the authorities. The European Commission has stated that it’ll look to quantify food losses and waste at the production levels and implement measures to mitigate them. However, no firm pledge has yet been made on how it will do so.

What Other Areas Could Be Targeted?

Even if waste cannot be avoided entirely, perhaps it can be used to create useful components, such as chemicals and energy? This is where biorefineries come in.

The Commission says it “will take action to speed-up market adoption” biorefineries, solar panels and other energy efficiency solutions in the agriculture and food sectors. Again, there’s no solid pledge on the ramping up of the EU’s biorefinery network in the Farm to Fork strategy.

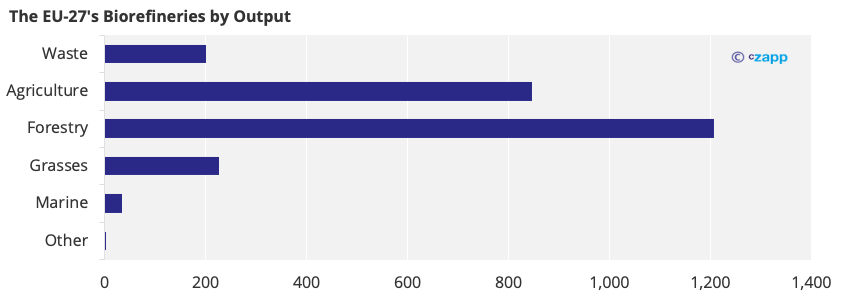

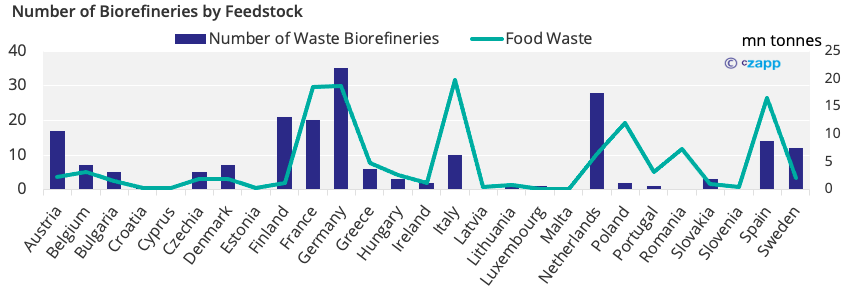

The EU currently has 2,362 biorefineries, with most of the capacity concentrated in Germany and France, but just over 200 of these biorefineries use waste as a feedstock. Of these 201 biorefineries, 83.6% are operating commercially, while nine are in the research and development stage, and a further 24 are in the pilot or demo stages.

Most of the EU-27’s biorefineries use agricultural and forestry inputs. This could be ideal for the agricultural industry, provided the inputs used are materials that would otherwise go to waste rather than primary materials that could have another use.

Another consideration, though, is each country’s biorefinery capacity compared with the waste it generates. While France and Germany are both well placed to dispose of food waste through their existing biorefinery network, other high waste generating countries have limited capacity.

Italy, for example, generates more food waste than Germany and France, yet has about half the capacity of France and one-third of Germany’s. Spain and Poland are also relatively high waste generators with limited biorefinery capacity.

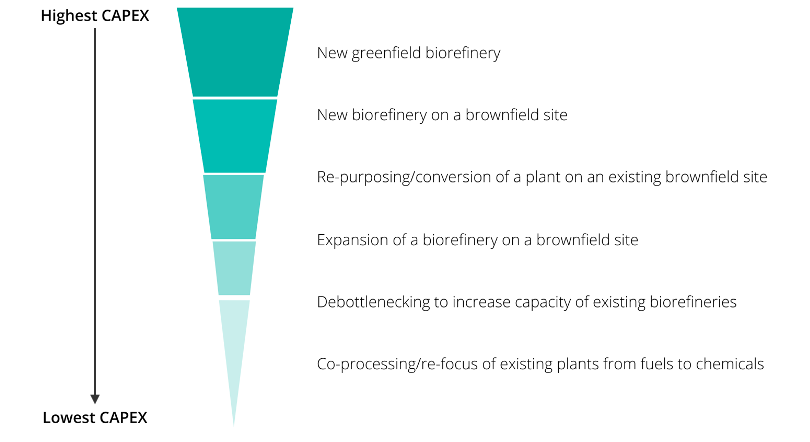

Although there’s been interest in building 300 more biorefineries by 2030, a 2021 independent expert report prepared for the European Commission admits that a goal of 42 biorefineries in this period is much more realistic. Even for just 42 new biorefineries, the estimated capital investment required is in the range of EUR 3.4 billion to 13.7 billion. Some investments would be more expensive than others depending on a number of factors, including whether they’re brownfield or greenfield developments.

Additionally, due mainly to the high capex requirements, high labour costs and high production costs, many of the products produced in biorefineries aren’t yet cost competitive with the original products produced in a traditional crude refinery, but this is slowly changing.

Now, propylene glycol, methanol and certain resins are becoming cost competitive in biorefineries. There’s also a good prospect for micro-fibrillated cellulose to become cost competitive in the near future. It’s worth noting that performance is often identical to the original chemicals.

Another benefit is that this production method reduces greenhouse gas emissions, sometimes substantially. The production of lactic acid and PLA in a biorefinery using fermentation of sugars has the potential to reduce greenhouse gases by up to 70% compared with steam cracking of naphtha.

What Can Consumers Do Until There’s a Better Solution?

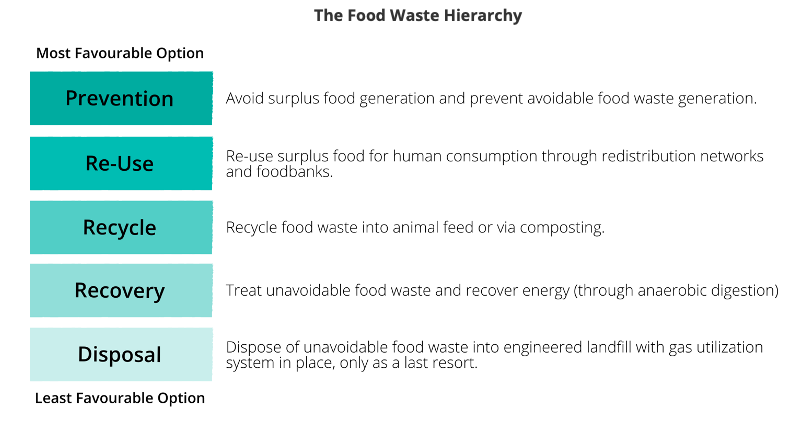

Sometimes, food waste cannot be prevented, which is why priority levels have been devised in the food supply chain to ensure potentially wasted food first goes to the most appropriate source.

In the food waste hierarchy, the best use of food is for human consumption, or in other words, when food waste can be prevented. Next comes food recovery, including redistribution of leftover foods to food aid organizations. This is followed by using food waste for animal feed, anaerobic digestion and, finally, landfill.

Concluding Thoughts

Although food waste can be tackled in a variety of ways, it’s essential that everyone across the supply chain participates, including final consumers. The actions that can be taken, especially further up the supply chain, could present a golden opportunity for the EU to meet its decarbonization goals.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

The EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy (At a Glance)