- India may become a net importer of sugar.

- We don’t think Indian cane production will be able to keep up with increasing ethanol demand.

- Any increases in cane acreage will likely go towards ethanol rather than sugar in the coming years.

Global Sugar Production is Barely Growing

Global sugar production has barely grown in the last decade. Meanwhile, consumption has been growing at around 1% per year. The world therefore needs 14m tonnes more sugar than it did 10 years ago. Across this series, we assess the feasibility for cane and beet expansion in some of the world’s largest sugar-producing regions: India, Brazil, Thailand, and Europe.

Can India Help?

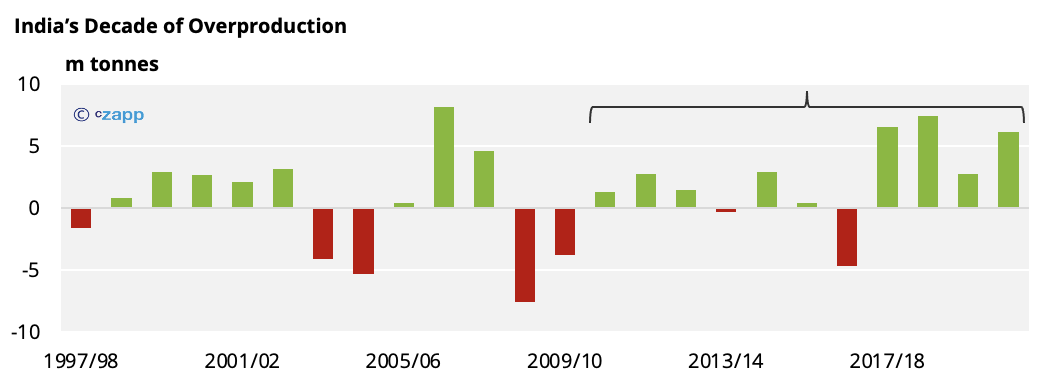

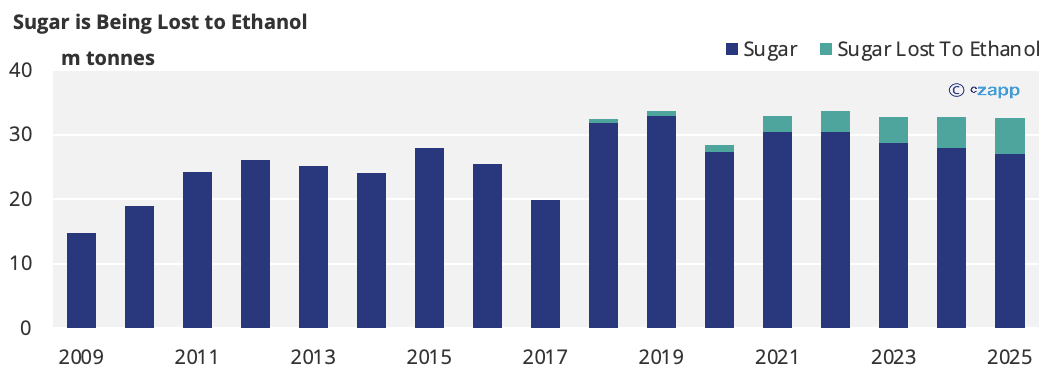

We don’t think India will be able to help in the coming years. Its sugar production should fall as more sucrose is diverted to ethanol production. This should slowly end its consistent overproduction of sugar caused by high cane prices, which are designed to support rural incomes.

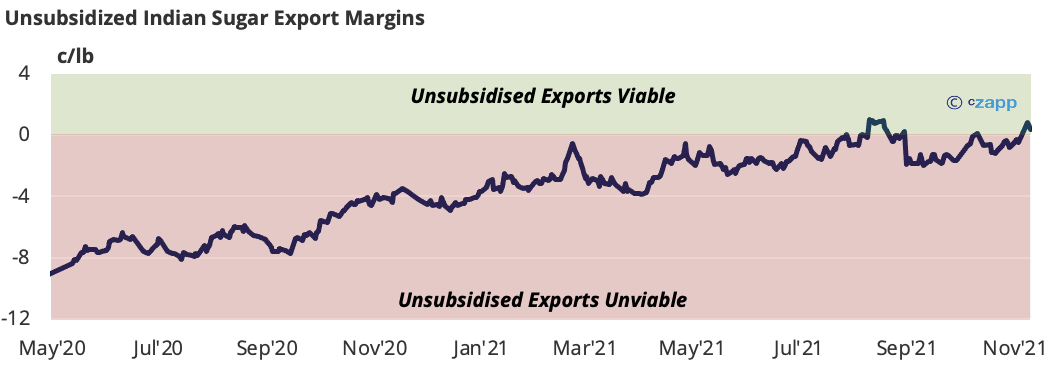

In the past, this was not a problem as the Government gave the mills subsidies to export their excess sugar. However, the Government now knows that it can’t use these subsidies from 2023 under WTO rules. Without a subsidy, raw sugar exports are only just workable at current prices (20 c/lb). If sugar prices fall lower, India’s market could be flooded with sugar that cannot be profitably exported.

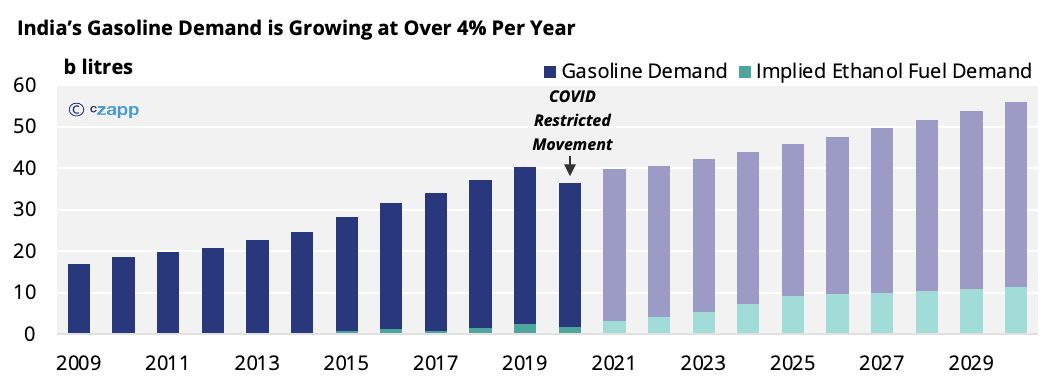

To address this issue, the Government is focusing on developing a local cane ethanol industry, like that in Brazil. In the coming years, more and more sucrose will be diverted to make ethanol rather than sugar as part of India’s E20 ethanol mandate. The Government has set cane ethanol prices at a high enough level to ensure millers will make as much ethanol as they can. Once the 20% ethanol blend is achieved, this would mean diverting around 6m tonnes of sugar each year to ethanol.

As gasoline demand is continuing to grow in India (by over 4% per year), demand for fuel-grade ethanol will also keep increasing (even once the blend reaches 20%). The loss of sugar production could therefore keep creeping up.

In this situation, India would no longer produce surplus sugar for export onto the world market. It would either need to import sugar or increase cane acreage and/or productivity to satisfy domestic demand.

It seems unlikely the Government would want to return to a situation where there’s consistently too much sugar. However, if India’s ethanol programme becomes as flexible as Brazil’s, it could mean India can provide additional sugar to the world market in seasons of tight supply, where sugar prices are well above 20 c/lb.

Can India Increase its Cane Output?

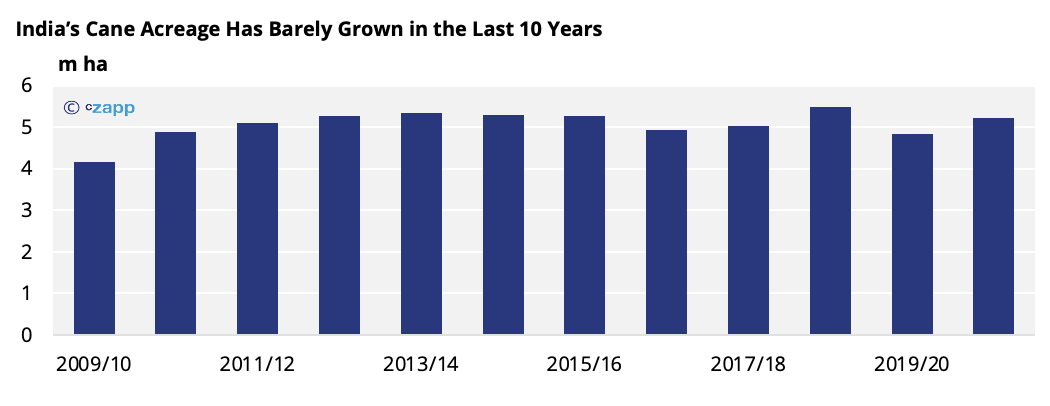

Indian cane acreage has barely grown in the last 10 years and usually covers 5 to 5.5m hectares of farmland.

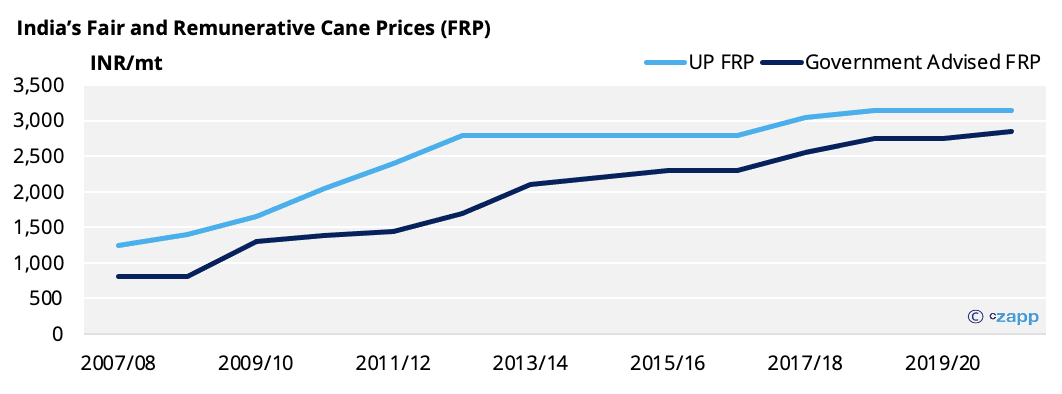

This is despite the increasing cane price paid to farmers, which is set by the Government each season. Farmers ultimately decide cane acreage, but the Government decides the cane price paid to farmers.

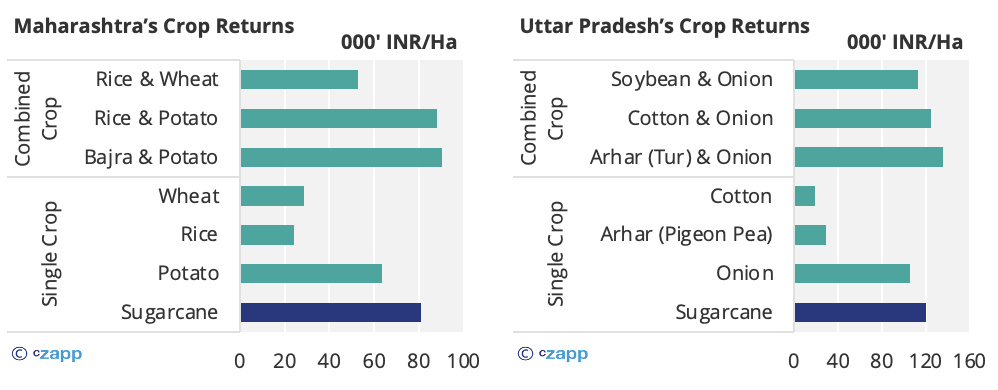

To increase cane acreage, a much higher cane price is required. Cane is already one of the most attractive crops to farmers. However, cane prices now need to encourage less efficient farmers, or those further away from a mill, to grow more cane.

However, a higher cane price would lead to increased domestic sugar prices, which the Government wants to avoid as it’s a key source of food for much of the population. We therefore think a significant increase in cane prices is unlikely.

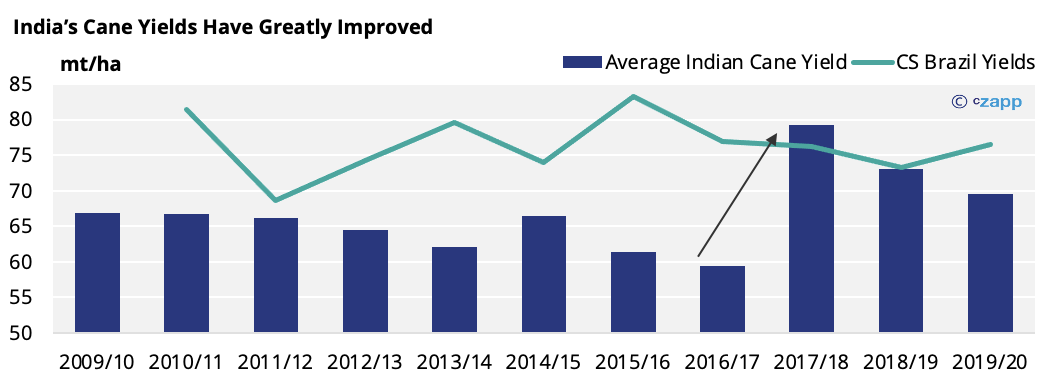

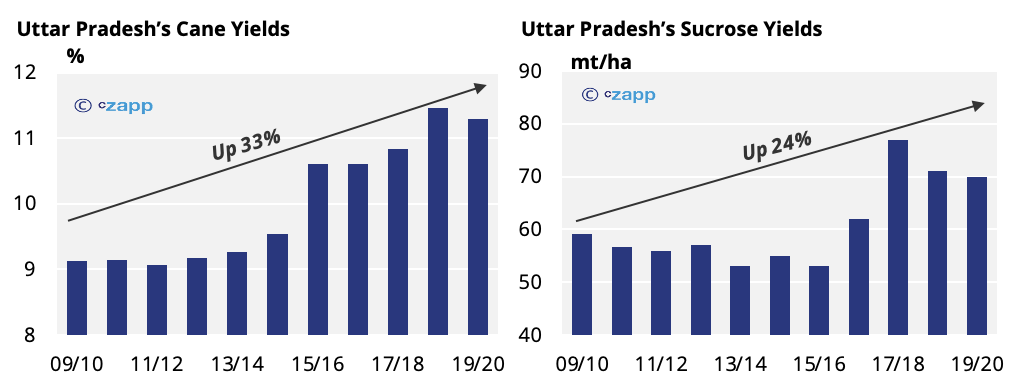

This leaves cane yields, where India has made real progress in the last few seasons. The volume of cane harvested per hectare is now very comparable to that in CS Brazil.

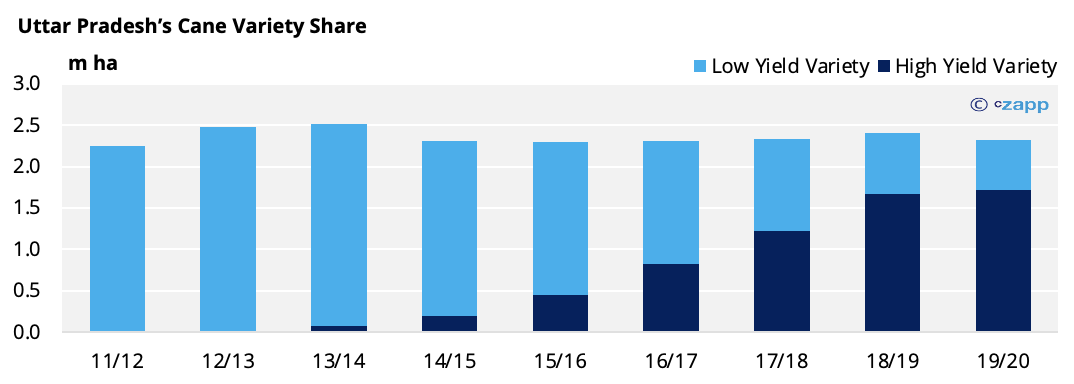

The progress is particularly clear in Uttar Pradesh, which makes up almost half of India’s cane acreage. These increases are largely down to a new sugarcane variety (called Co-0238), bred by ICAR, which has unusually improved both cane and sugar yields.

The experience in Uttar Pradesh highlights the length of time needed to launch, test, and approve a new variety; it’s not a short-term fix. After the higher yielding variety was launched in 2009, it was eight years until more than half the cane area in Uttar Pradesh was cropped with the new, higher yielding variety. There’s also significant investment required when it comes to breeding new variants.

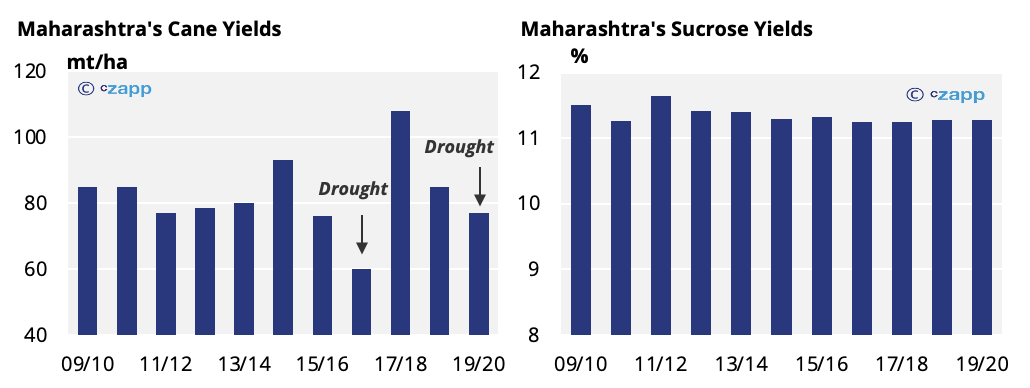

In Maharashtra, the other major sugarcane state, cane yields are generally better than those in Uttar Pradesh, but the new variety in Uttar Pradesh makes sucrose yields comparable.

The Vasantdada Sugar Institute in Pune is helping Maharashtra develop its own cane varieties. Primary trials in 2020 were very successful, with yields increasing by 25 mt/ha and improvements also seen in sugar content.

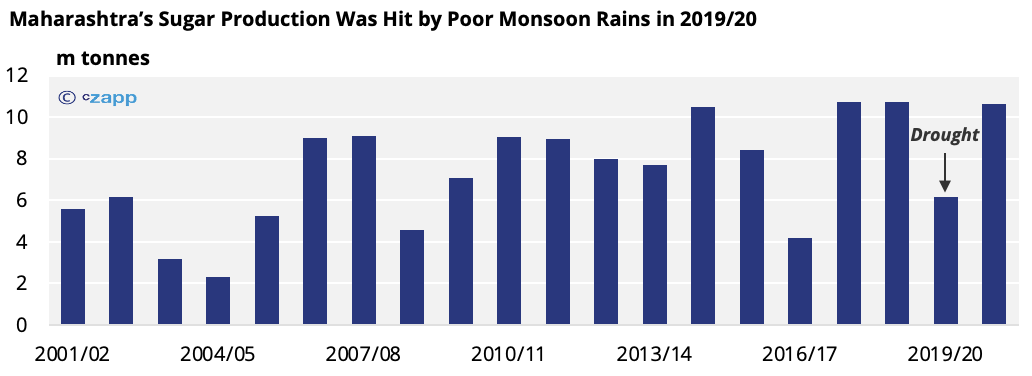

Based off the area planted in 2020/21 (1.14m ha), these yield increases could lead to an extra 28m tonnes of cane, which equates to more than 3m tonnes of sugar. Other varieties that are more resistant to drought are also in development – a very important consideration in Maharashtra given both the 2016/17 and 2019/20 seasons were badly affected by a lack of water.

Again, it could take several years before these varieties become widespread, but this could help India meet its sucrose demand (for both sugar and ethanol) in the longer term.

There are quicker and cheaper ways of increasing yields, which India could try, such as improved cane irrigation, increased mechanization, and other agritech.

India’s existing flood irrigation systems are very inefficient and lose about 65% of the water before it reaches farmland. Consequently, India’s struggling with its water resources; 17% of the global population lives in India but it’s home to just 4% of freshwater. Cane requires a large amount of water compared to other crops. In Maharashtra, cane covers 4% of farmland but uses more than two-thirds of the state’s irrigation water. The crop is still very reliant on monsoon rains each year, though, as demonstrated by the poor crop in 2019/20.

Heightening the use of technology and mechanization will undoubtedly make operations more efficient and improve yields. However, as so much cane is grown on small farms, the mechanization of harvesting may not make much economic sense.

What About Milling Capacity?

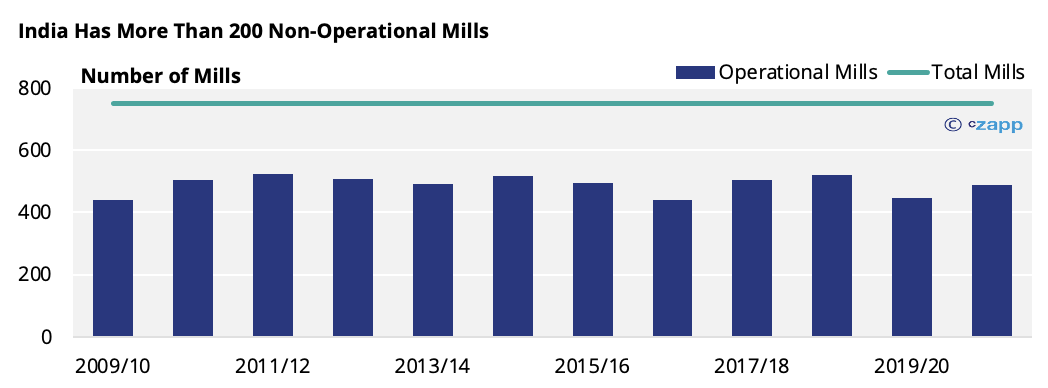

In India, there are 461 mills that have been operational in recent seasons, but there are a further 290 mills classed as non-operational. In theory, this means there’s spare milling capacity that could be utilized to make more sugar if more cane is grown. However, we believe many of these mills have been shut for years, which means there will likely be significant re-commissioning costs.

With sugar prices around 20 c/lb, we don’t think there would be enough of a price incentive to invest in recommissioning these mills. Similarly, new milling projects require a high initial investment and would take a few years to become operational. This means only an extended period of high prices, well above Indian export parity, will see new mills being built. New mills also require governmental approval, which could further delay or stop the process.

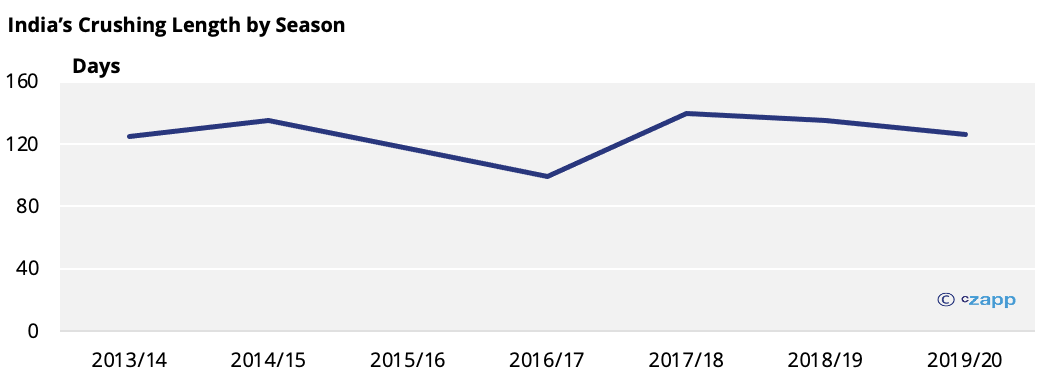

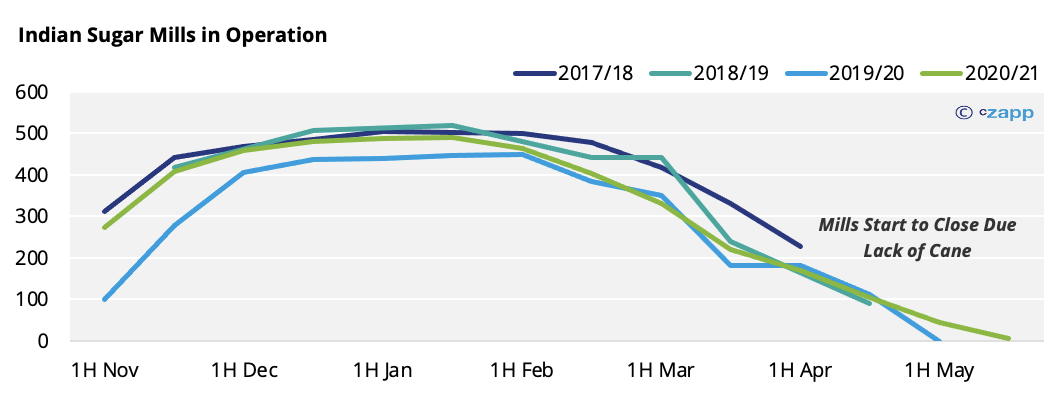

The easiest way to increase crushing capacity would be for mills to extend their campaigns. India’s crushing season usually lasts fewer than 140 days with cane availability being one of the limiting factors.

It should therefore be possible to process more cane if it’s planted near to the mills that typically suffer from a lack of cane. The pace of crushing currently slows during the final few months of the season (March to May) as some mills start to close. However, we don’t think the crushing season can be extended much beyond May, as heavy monsoon rains and flooding would make operations too difficult.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

The World Needs More Sugar…Who Can Help?

Explainers That May Be of Interest…