- Both Brexit and COVID-19 have been blamed for labour shortages across the UK.

- A shortage of farm workers is worsened by a lack of lorry drivers to transport produce.

- The food industry and supply chain are calling for several measures to alleviate the pressure.

The Supply Chain is Struggling

Low availability of materials and shipping vessels are pushing prices up, but all this is underpinned by a chronic lack of labour. The UK prepares to end the furlough worker subsidy scheme at the end of the month, which many think will alleviate the issues as more workers return.

But some experts warn that the end of the scheme will have little impact due to a mismatch in skills required for jobs and those out of work. While the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) Vice President, Tom Bradshaw, calls the notion “simplistic”, The Food and Drink Federation (FDF)’s Chief Executive, Ian Wright, says today’s labour shortages are caused by “a multitude of structural factors beyond those created by Covid-19 and the end of the Brexit transition period.”

The Type of Work

A new report by several industry organizations including the NFU, FDF and AIC estimates that the average vacancy rate across the UK’s food and drink businesses is 13% with about half a million positions currently available. Some labour providers are seeing a recruitment shortfall as high as 34%.

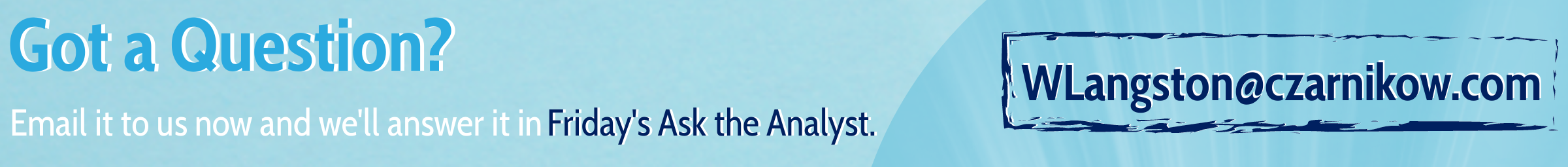

In UK agriculture, there are relatively few full-time regular positions available and the number of these positions available are decreasing. From 2000 until 2014, the last year for which the data is available due to a change in reporting methods, the share of regular full-time workers as a proportion of the total agricultural workforce dropped from 44.1% in 2000 to 37.6% in 2014.

Most UK workers prefer traditional employment to less formal options, with a survey showing that 76% would feel more secure in permanent employment. In the survey conducted by Glassdoor, both salary and benefits ranked as the top priorities, and a survey by Deloitte showed that 65% of Millennials prefer full-time employment due to the job security and fixed income it offers.

In October, the NFU said only 11% of seasonal workers in the 2020 season were UK residents. Prior to 2013, UK seasonal farm workers came primarily from Romania and Bulgaria under the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS), but this initiative was retired in 2013 when restrictions on EU work for those nationalities no longer applied.

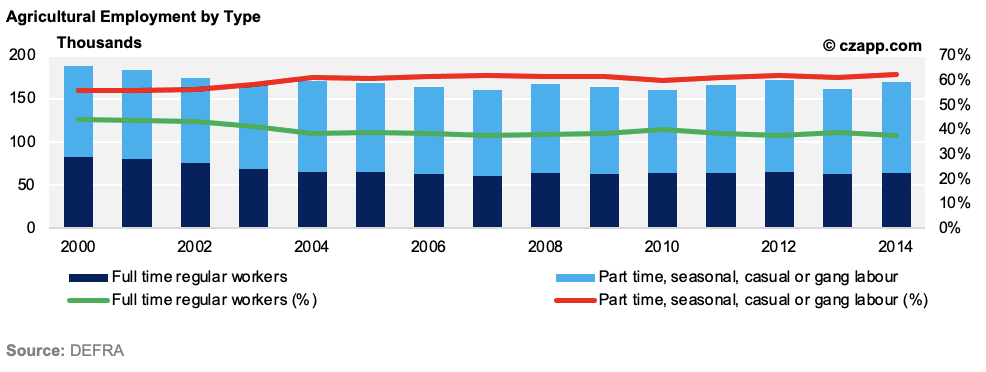

However, after Brexit, the restrictions on UK work again applied to EU nationalities so the UK government launched a new Seasonal Worker Pilot (SWP) program. The extended pilot program is managed by the Home Office under the T5 (Temporary Worker) Seasonal worker route. The total number of T5 visa applications significantly declined in 2020 to just over 20,000 from more than 50,000 in 2019. Authorities recently expanded the number of visas available under the SWP program from 10,000 in 2020 to 30,000 in 2021 to help ease pressure on farmers. But according to the NFU, the industry will still be short more than 70,000 seasonal workers.

Surveys conducted between 2014 and 2016 highlighted concerns over recruitment. One in four dairy farmers experienced difficulties recruiting the right staff and 75% said they were recruiting from overseas, specifically from Eastern Europe. Half of those international workers were skilled or semi-skilled, which is particularly important given that only 9% of skilled or qualified adults are likely to consider working on a UK dairy farm, according to the Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers.

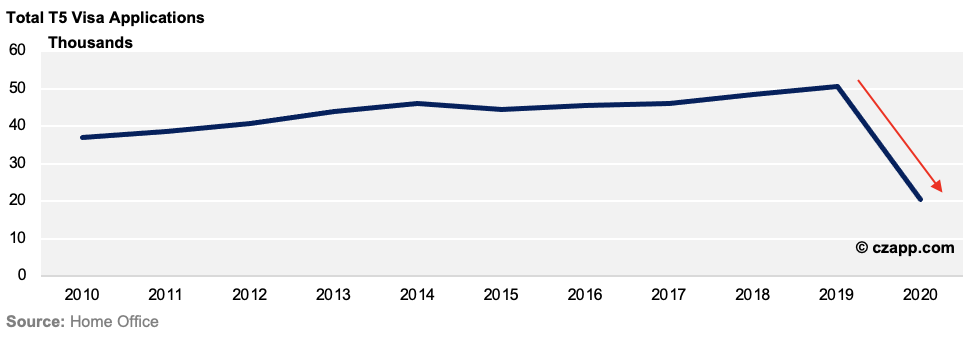

In the chart below, the data was not available for 2020.

Restrictions on Movement

Recent movement-restriction events, such as Brexit and COVID-19, have compounded this issue across many agricultural sectors. Reports suggest that the 2021 summer harvest has been particularly tough on farmers as they struggle to find labour and the cost of inputs rise. Farmers have been forced to leave produce to rot on the vine for lack of staff and have even given food away for free.

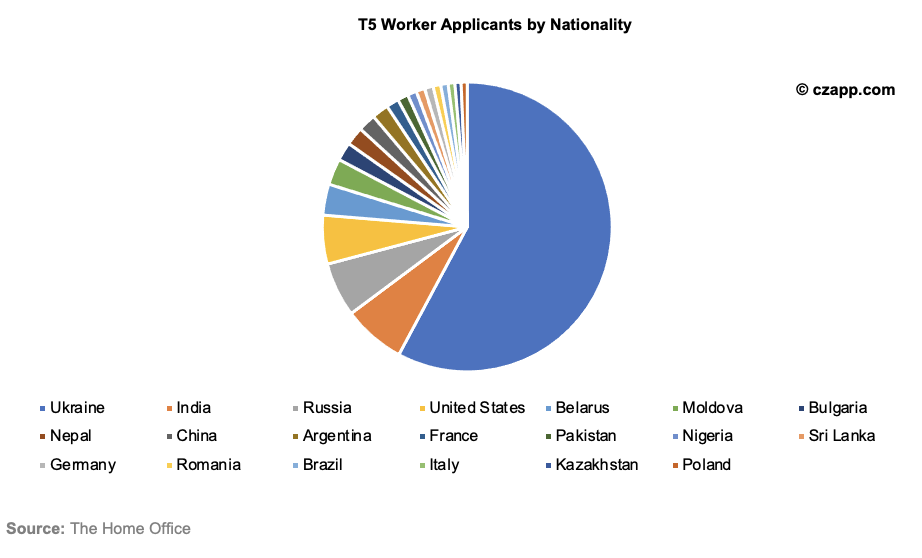

While most fruit pickers tend to come from Bulgaria or Romania, about 57% of migrant workers in dairy farming are from Poland and Latvia. In a breakdown of T5 visa applications from the first half of 2021, very few are from these origins but there’s a large component from Ukraine. Notably, in 2019, the UK government began a drive to recruit agricultural seasonal workers from Ukraine, Moldova, and Russia.

Finding the Right Kind of Labour… For the Right Price

So, why is it so hard to recruit and retain British workers for farms? One issue is location. Farms are generally not found in locations with high levels of unemployment and, often, the British population is unwilling to move to the rural setting demanded by working on a farm. The demanding hours of farm work, combined with a lack of public transport options, means it’s difficult to find willing candidates for farm labour. The issue is compounded by the fact that job vacancies are at their highest levels in a decade as of Q2’21.

Another reason for the difficulty in recruitment is the demands of the job. According to a 2013 government report by the Migration Advisory Committee, farmers surveyed reported that British workers “either cannot or will not work at the intensity required to earn the agricultural minimum wage”.

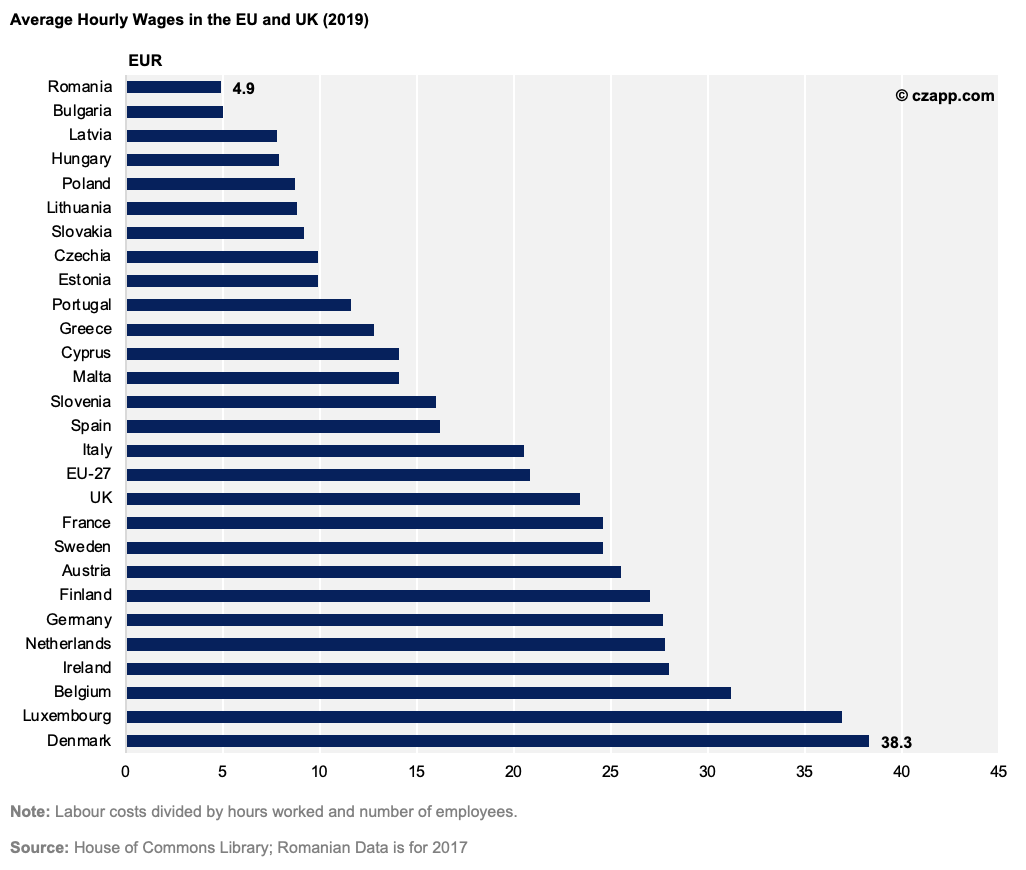

There’s also far stronger motivation for some non-British workers to take jobs on UK farms. According to Migration Watch UK, an average Romanian worker could earn £1,400 per month, or 3.5 times the average monthly salary in their home country. In the UK, the median weekly earnings for full-time employees in all sectors is around £585.50 per week, equating to about £2,537 each month before tax. This means that, for British workers, other professions may be more attractive than agriculture and can provide less demanding workdays.

Farmer Margins Squeezed

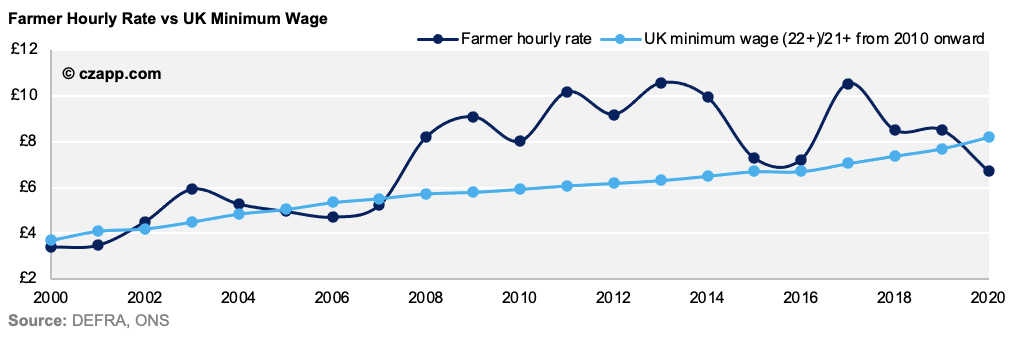

To address the issues, some organizations, including the Gangmasters’ Licencing Authority (GLA), have called for a more competitive and attractive labour market for talent retention. This translates to an increase in salaries, but this may prove more difficult in practice as UK farmers are already hard-pressed by tight margins.

Farm business income comes through four sources: agriculture, diversification, agri-environment, and the Single Payment Scheme (SPS). While the SPS is generally referred to as a subsidy, Defra says this is inaccurate as the payment is designed to compensate for the money a farmer would’ve made from land that’s designated to improving and protecting the environment.

The below chart takes total farming income and divides it between the number of farmers, partners, directors, and spouses on UK farms. The per capita profit is then divided over a farmer’s 65-hour average working week to generate an hourly working rate. This rate is extremely volatile and can often come very close to or even fall below the national UK minimum wage, as was the case in 2020.

Farmer margins are already precarious, and profits are topped up by the SPS payment. According to DEFRA, the average Basic Payment across all farm types was £27,800 for the 2019/20 year. In the same year, at least 12% of each farm type failed to make a profit and this figure is much larger for some types, such as lowland grazing livestock.

And according to Tom Bradshaw from the NFU, farmers have tried to drive recruitment with increased salaries, to no avail. “Farm businesses have done all they can to recruit staff domestically, but even increasingly competitive wages have had little impact because the labour pool is so limited – instead only adding to growing production costs,” he says.

Labour Issues Extending to Supply Chain

For the agriculture industry, the labour problem extends far beyond the farm itself. A chronic shortage of HGV drivers means that, not only are farmers struggling to get food to the points of sale, but they’re struggling to secure feedstocks and critical inputs.

Ed Barker, Head of Policy and External Affairs at the Agricultural Industries Confederation (AIC) told Czarnikow that members are witnessing difficulties in some products being delivered as accompanied haulage from the EU to Britain because of driver availability and production challenges. This includes some crop protection products and fertilisers that have been affected by high energy prices and production challenges in the USA and China.

“These problems are unlikely to improve as we go into the winter,” Barker added.

The lack of cold storage options isn’t helping the situation, according to the UK Cold Chain Federation, which says the unexpected high demand caught the industry off guard. “After many years of a relatively static property market, a growth in demand is fuelling investment. Short-term factors like COVID-19 and Brexit have shown that there’s not enough cold storage space in the UK market to cope with spikes in demand.”

Brexit-Related Complications

Woes over HGV drivers are compounded by UK-EU “trade friction”, according to AIC’s Barker. “Many British businesses trading certain seeds, crops and animal feeds are experiencing ongoing challenges as a result of the UK-EU trade agreement,” he says. “This has further added costs to businesses who supply both domestic and international customers.”

When surveyed by the AIC this year, 94% of member businesses have experienced delays or friction on exports to the EU since January 1, with 65% even reporting difficulties on exporting from Britain to Northern Ireland.

The UK government recently announced that it would further delay implementation of post-Brexit border controls on agricultural imports from the EU to mitigate the pandemic-related disruption.

The additional requirements include pre-notification of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) goods, which have now been delayed until 1st January 2022 instead of 1st October 2021. Export health certificates and safety and security declarations will now not be required until 1st July 2022.

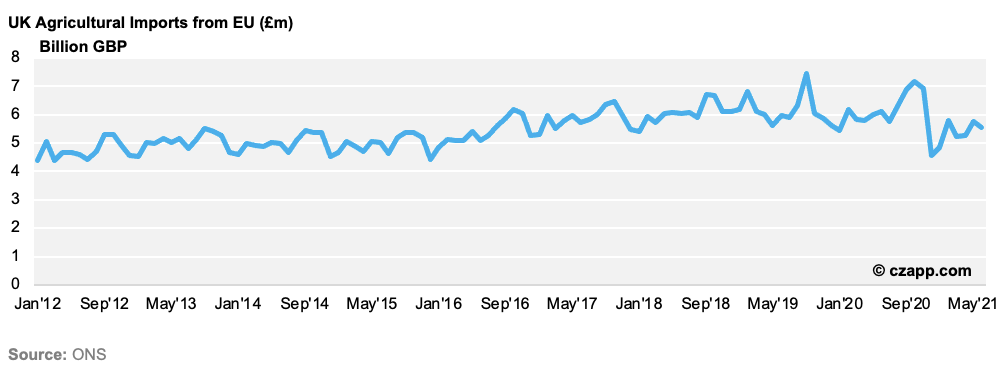

While the AIC says it welcomes this announced delay, Barker warns that “the process cannot continue indefinitely.” UK agricultural imports from the EU already dropped sharply in 2020 and have so far failed to recover in 2021.

Talent Pipeline

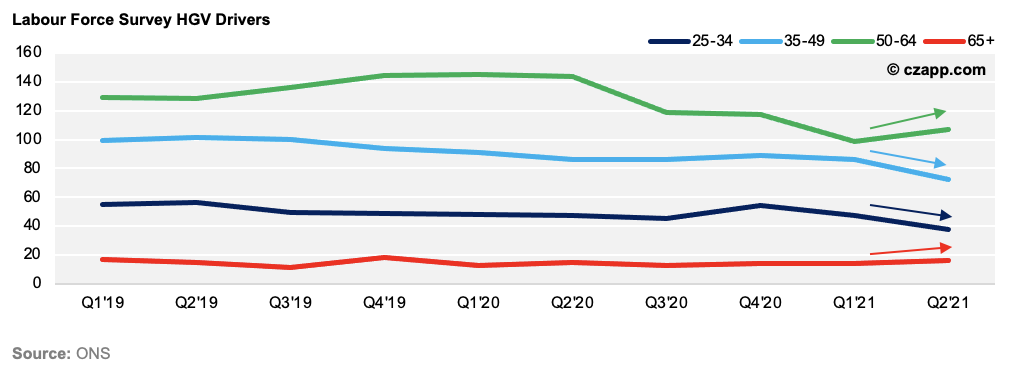

As the industry focuses on urgently training more drivers, there’s a need to also look at the coming talent pipeline. The largest age group of HGV drivers is consistently between 50 and 64 years old, while the number of 25- to 34-year-olds in the industry has been dwindling since the beginning of 2019.

The total number of HGV drivers has dropped by about 22% since Q1’19 to 233,000 drivers. Amid high demand, this lower availability and apparent reluctance of the younger generation to enter the business is causing concerns for those industries reliant on transportation.

Recently, the UK Department for Transport, Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency, and Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency announced changes to tests that they hope will speed up the process to obtain an HGV license. However, licenses can already be obtained relatively quickly, in as little as eight to 10 weeks. It seems there’s reticence to enter the industry in addition to bottlenecks in the testing process.

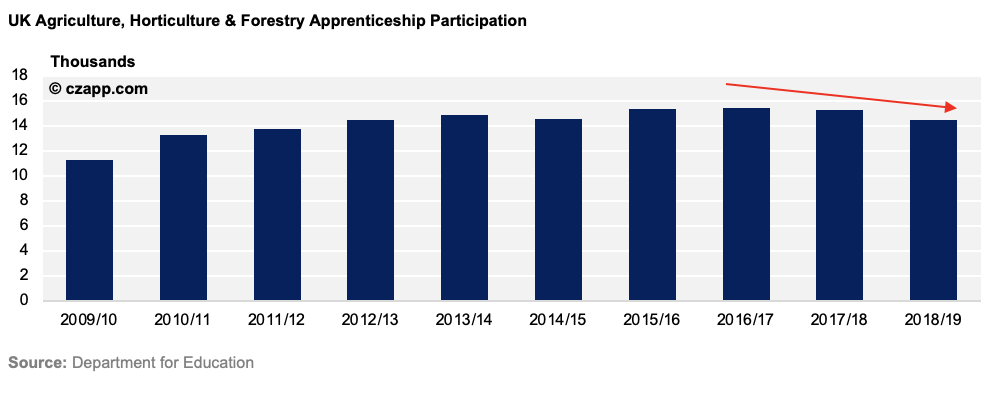

Not only is there a shortage of drivers, but future talent for the agriculture industry also appears to be dwindling. In the 2017/18 academic year, participation in the UK’s agriculture, horticulture and forestry apprenticeship programs began to slide and dropped again in the 2018/19 academic year. Full year figures for 2019/20 are not yet available but will likely show a further drop as admissions in education institutions fell during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

So, What’s the Solution?

With the potential to recruit British talent to farms in large numbers unlikely, many industry bodies have called for the freedom of movement issues to be addressed. With a greater talent pool to recruit from, it’s far more likely that farmers will be able to secure the labour they need, but visas are a huge barrier.

Richard Harrow, Chief Executive of the British Frozen Food Federation, says that labour shortages across the supply chain are creating the “perfect storm” of increasing costs for members.

“Whilst the long-term solution is to train more UK nationals, we will only avoid further disruption to food supplies and inflationary cost increases by taking … temporary visa measures.”

The measures he refers to are the introduction of a 12-month COVID Recovery visa scheme, as well as a revision and expansion of the SWP Scheme that would allow an increase in the number of foreign seasonal workers able to work in the UK.

Tom Bradshaw from the NFU echoes the call for additional visas for seasonal workers. “A short term COVID Recovery Visa, alongside a permanent Seasonal Workers Scheme, would be an effective and, frankly, vital route to help the pressing needs of the industry today. It would also give us time to invest in the skills and recruitment of our domestic workforce,” he says.

The UK’s Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) is currently carrying out an urgent review on the impact of ending free movement on the adult care sector, and the same action could be taken for the agriculture sector, which strongly depends on migrant labour for several complex reasons.

If action is not taken, there could be severe consequences for the UK’s supply of food and drink, with some supermarkets already warning of potential shortages over the busy Christmas period. The FDF’s Wright says that without fast action, the labour challenges will continue. “If they do, we can expect unwelcome consequences, such as reduced choice and availability for consumers, increased prices, and reduced growth across the domestic food chain,” he warns.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…