- We think Thai sugar consumption could have peaked.

- There’s been a substantial negative impact from the COVID-19 pandemic, but this is not the whole story.

- As Thailand’s Excise Ministry pushes back the sugar tax increase scheduled for next month, we examine how consumption has changed.

Sugar Consumption Has Dropped

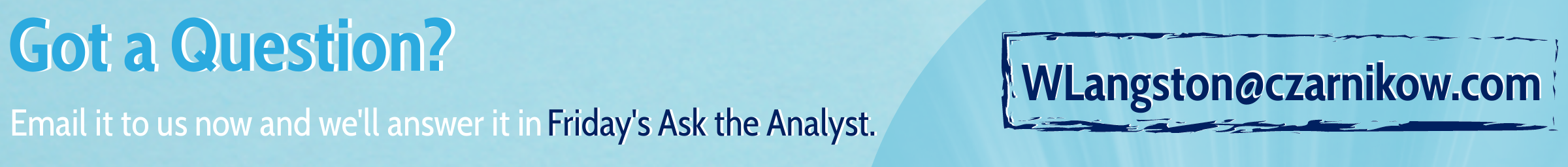

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on consumer habits, and, on the face of things, it seems to have impacted Thai sugar consumption. Thailand’s per capita sugar consumption dipped in 2020 after a period of relative stability since 2015.

With consumption levels now back on par with those seen in 2010 and 2011, the question is whether COVID-19 caused the drop, or whether it exacerbated an existing trend. Another question is whether consumption levels will return to previous highs.

From the chart above, it’s clear that per capita consumption did drop slightly between 2018 and 2019, which suggests that COVID-19 is not completely to blame and that perhaps the drop is part of a wider trend of sugar reduction in Thailand.

Thailand’s Tourism Decline

Of course, the first explanation that should come to mind when we look at the 2020 decline is the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated implications.

Thailand’s tourism sector accounts for one fifth of the country’s GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. Due to global travel restrictions imposed in 2020 resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand’s GDP dropped by 6.1%, dragged down by a contraction in accommodation, arts, recreation and entertainment and transportation.

It’s estimated that 21% of tourist spending is on food and drinks. With an estimated spend of 3 trillion Thai Baht (91.6 million USD) in 2019, this translates as 19.2 million USD on the food and drinks sector.

Figures show that visitor numbers tumbled to 6.7 million in 2020 from 39.8 million in 2019, meaning there’s no doubt the travel restrictions had an impact on sugar consumption.

Underlying Sugar Consumption Drivers

Sugar consumption is primarily driven by population growth, urbanization and increases in wealth and disposable income. As the population grows, countries are bound to register greater sugar consumption (although not necessarily greater per capita sugar consumption). Urbanization and increases in disposable income generally drive demand for high-energy convenience food – and larger quantities of it.

The Thai Situation

In Thailand, sugar consumption is already mature at above 30kg per person per year.

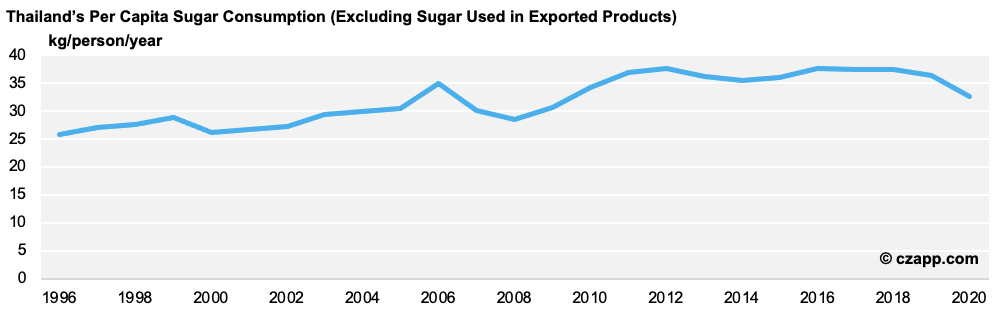

Looking at sugar in products (as opposed to tabletop), beverages are the largest sector in Thailand, but a substantial amount also comes from fruit and dairy products.

A Tax on Sugar

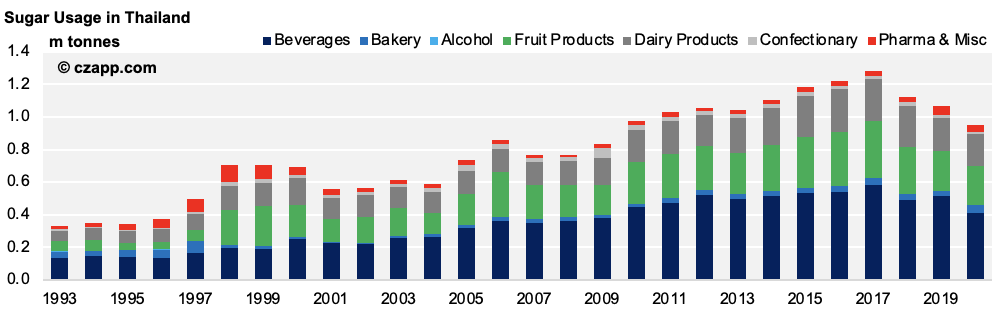

Thailand’s sugar tax – implemented in 2017 – was designed to curb sugar consumption whilst also generating funding for the public purse. The tax is composed of two components: an ad valorem rate and a tiered rate in THB/litre based on sugar content in g/litre. Subject to rate increases every two years, the next increase was set to take place on October 1 but has been pushed back by one year to account for the economic pressure felt by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The October 2022 change will increase the tiered rates for drinks containing more than 6g of sugar per 100ml, whether they contain added sugar or not.

The tax was combined with two other measures: an educational campaign called Fatless Belly Thais (FBT) and a soda ban in schools. The FBT program focused on the 3Es: eating, exercise and emotional control.

Like with all sugar taxes, question marks have remained over this one’s effectiveness. One study carried out over 2018 and 2019 showed that the sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) tax did lessen consumption patterns but only across certain demographics, including males, older people, the lower-income populations and the unemployed. However, the change was not witnessed across all socioeconomic groups studied, which calls into question whether it was the tax that affected consumption or something else.

There seems to be a substantial decline since 2017 in the consumption of beverages and fruit products. Notably, the tax imposed in 2017 doesn’t differentiate between added sugar and natural sugar, meaning the tax could at least partly account for the drops witnessed here.

Reformulations

Rather than a change of consumer habits, this dip in sugar consumption could be down to a lower available amount of sugar. Ahead of the sugar tax being imposed, many soft drinks manufacturers selling products to Thailand reformulated recipes and added new products to their portfolios. Tipico Foods, World Food International, Oishi Group, Ichitan Group and Sermsuk all announced reformulations and sugar reductions across some products. While they did not reformulate products, Nestlé and PepsiCo Asia launched new sugar-free ranges.

So, what’s caused the downward trend? One explanation of course is COVID-19, but this doesn’t account for the dip seen prior to 2020. Another explanation that ties in with the timeline is that the tax on sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) imposed in 2017 was extremely effective, having forced some – although not all – companies to reformulate products and release new low-sugar ranges. Awareness of the amount of sugar being consumed is likely to have increased following the introduction of the tax too.

These form part of the explanation, but the larger trend seems to be one of a ageing population where sugar consumption has little option but to drop.

Stagnant Population Growth

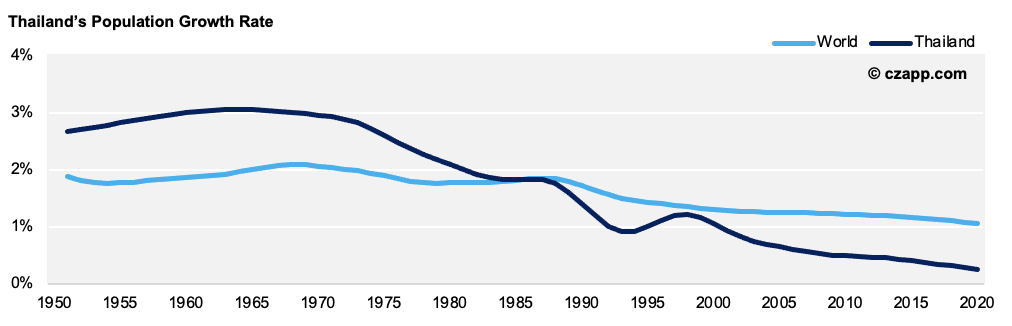

One consumption driver is of course an increasing population, but the data from Thailand shows a growth rate that’s well below the global average. This can be attributed to a highly successful birth control program called the Population Program, which was started in the 1970s – a time when women bore six children on average. The Government began a widespread educational campaign and heavily promoted the use of contraception.

This program was so successful that today, the total fertility rate (TFR) of a Thai woman is 1.51. This means Thai women are having 1.51 children on average, lower than the recommended 2.1-children “replacement rate” per couple.

The absence of a growing population impacts heavily on consumption trends. With an apparent plateau of about 37kg per person per year of sugar consumption in recent years, there’s little room for an increase in the country’s absolute consumption if the population continues to contract.

An Ageing Population

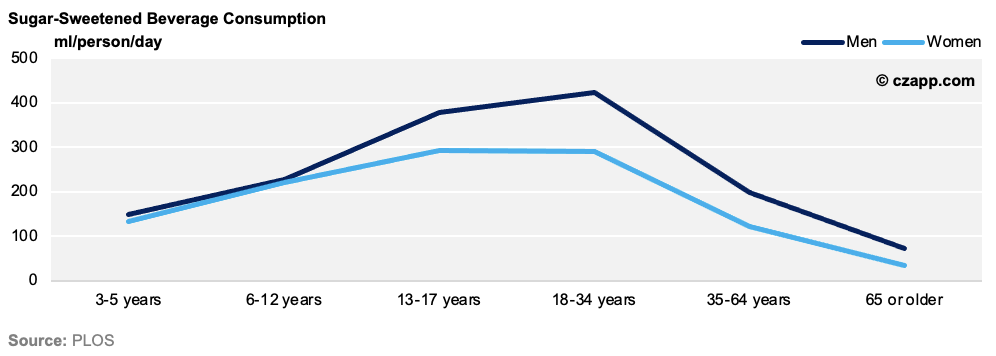

Suppression in childbirth rates also leads to an older population on average. This poses a problem for sugar consumption, which tends to decrease with age. In a global survey conducted by PLOS, both fruit juice and SSB consumption dropped globally with age, with the most substantial dip seen after the age of 40. When separated into regions, the trend held true across geographies.

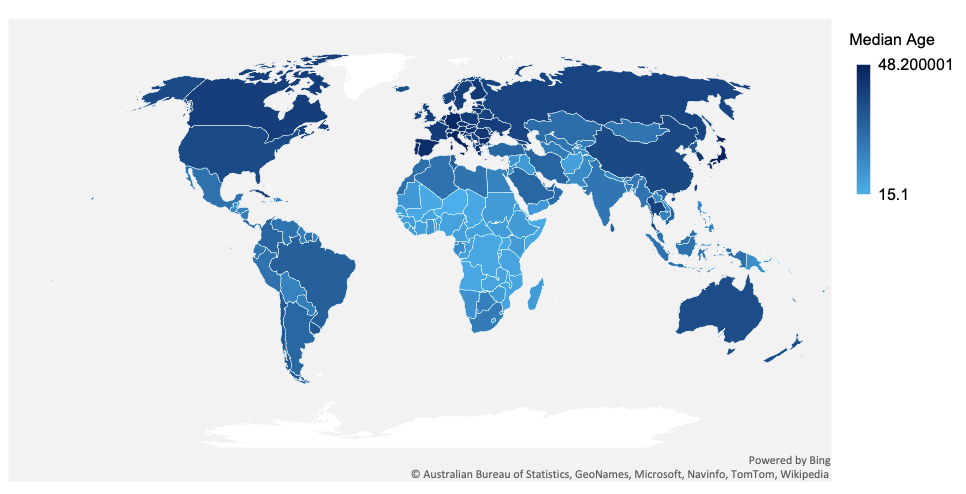

Thailand’s average age is 40.1 years, far higher than the global average of 29.6 years. It’s on the higher end of the scale, close to Japan, which has the highest median age in the world at 46.3 years. As Thailand’s population ages, this poses an obstacle for sugar consumption and, in combination with a dwindling population, could help explain the dip seen as early as 2017.

Bucking the Urban Trend

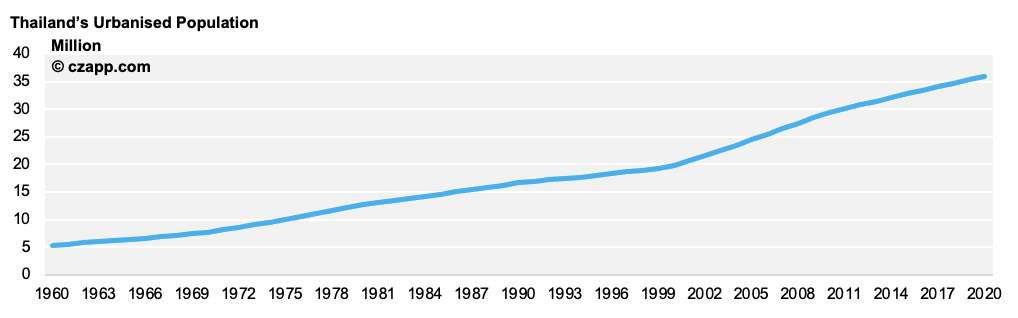

As populations urbanize, sugar consumption increases. The urban setting promotes the consumption of fast, convenient food, compared to the rural setting where generally much more planning has to go into meals and snacks.

Thailand has been urbanizing since the 1950s, followed by a rapid spurt after 2000. Just under 60% of the country’s population is now urban, compared to just over 15% in 1950.

Normally, it follows that industrial sugar use increases with urbanization, and this has been the general trend since 1996, with industrial sugar accounting for about 50% of the sugar in the Thai diet in 2017, up from 25% in 1996.

In this context, Thailand’s gentle decline in per capita sugar consumption looks troubling.

A Continuing Trend

Although it’s been established that COVID-19 and its restrictions played a significant role in the drop in sugar consumption in 2020, the real question is whether it’ll recover to higher levels when the effects of the pandemic subside. While an increase in demand from 2020 levels should be expected, especially from tourist-related consumption, it’s likely that Thai sugar consumption will continue to contract.

Birth control policies from the 1960s and 1970s were highly effective and their impacts are not easily reversed, meaning the country faces an ageing, declining population.

With sugar consumption already at levels far above recommendations and government legislation that aims to target the commodity, an increase in per capita consumption is unlikely. Given these factors, combined with a sluggish global economic recovery, it seems Thai sugar consumption has reached its plateau.

At the moment the slowdown in sugar consumption growth has been too recent to be reflected in any improvements in health statistics such as the Thai obesity rate. We will continue to monitor these for new emerging trends.

It’s also interesting to note that Thai sugar consumption might be falling; we previously wrote that Mexico’s sugar consumption is definitely falling. We think this shows how important the world’s newfound awareness about sugar intake is. Falling per capita sugar consumption isn’t now just a developed world phenomenon. Yes, it happens in countries like the UK and Australia, but it now seems that sugar consumption could fall in any country with a mature sugar market or a high proportion of processed food intake. This has quite profound implications for sugar manufacturers in many countries. We will continue to explore many of these countries in the future, with Brazil coming next.

Other Opinions You May Be Interested In…

- Can China’s Three-Child Policy Save Sugar Consumption?

- The Mexican Sugar Decline: Taxes, COVID or Something Else?

Explainers You May Be Interested In…

Interactive Data You Might Be Interested In…