- The world’s currently home to about 7.9 billion people, but this number’s growing constantly.

- The United Nations thinks there’ll be 9.7 billion people on the planet by 2050.

- With a need to increase yields without expanding footprints, food producers are constantly thinking up new ways to feed the growing population.

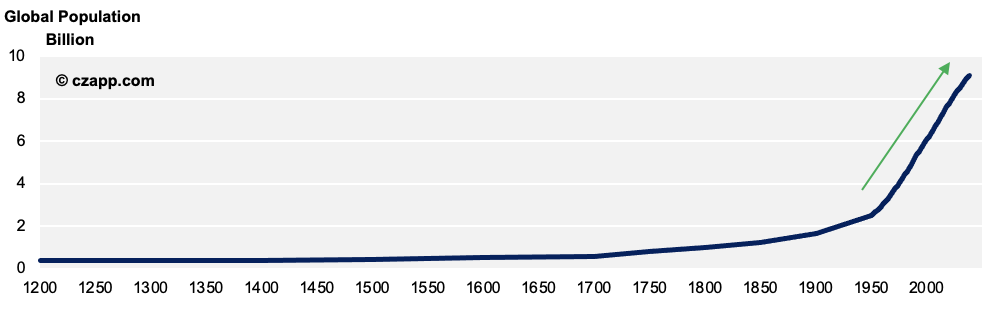

The Global Population is Growing, and Fast

The world’s currently home to about 7.9 billion people, and this number is constantly growing. In fact, it’s growing by around 225,000 people per day, and the United Nations thinks there’ll be 9.7 billion people on the planet by 2050.

As you can see, it was 1804 when the global population reached 1 billion, and it took a further 123 years to hit 2 billion. Population growth wildly accelerated when it reached 3 billion in 1960.

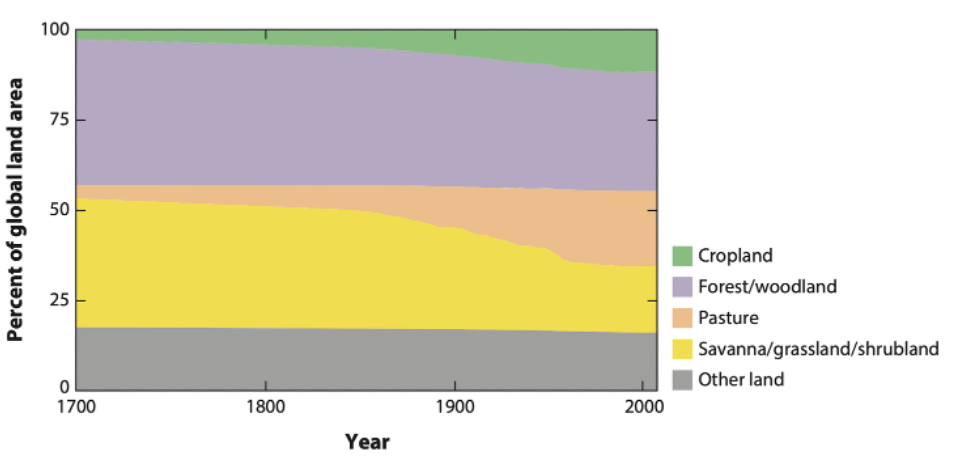

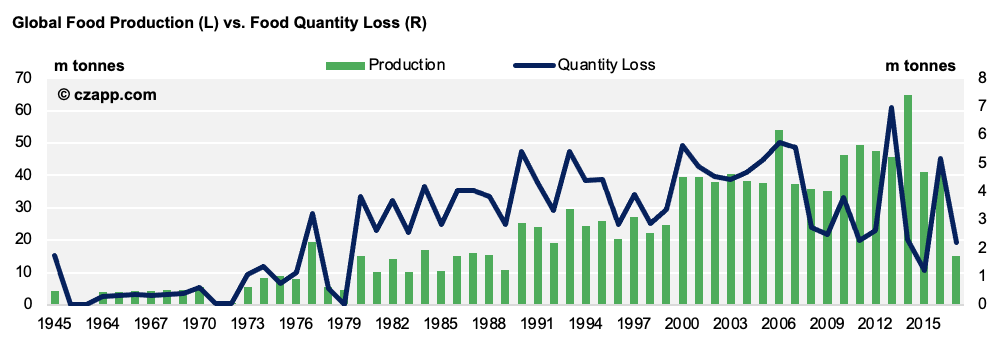

Such relentless population growth presents unique challenges for the global food industry. Since as early as 1700, the presence of cropland and pastureland has increased at the expense of savanna, grassland, shrubland, forest and woodland.

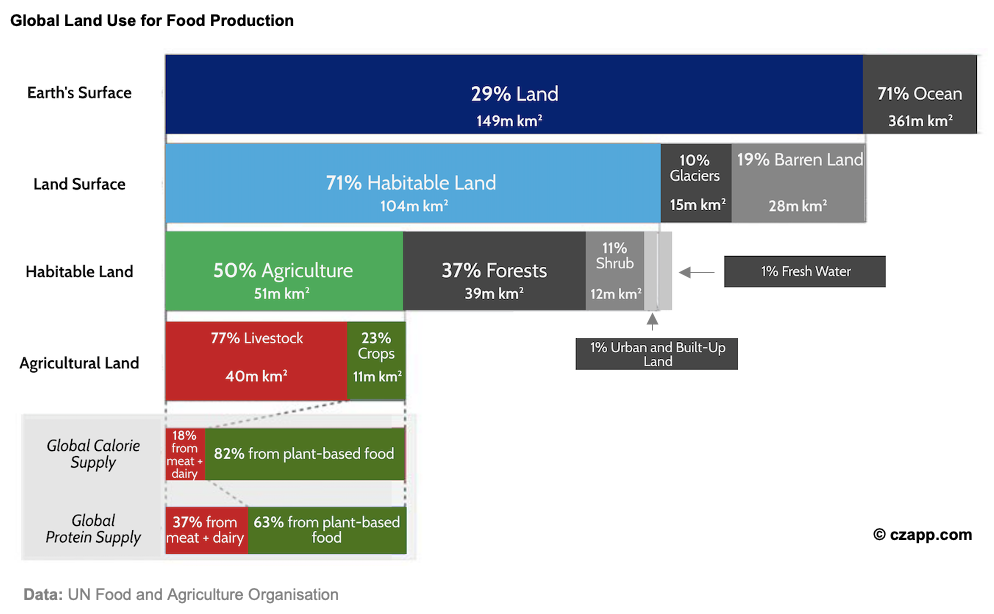

Today, of the 104 million km² of inhabitable land on earth, 50% is used for agriculture. Of this, 77% is used for livestock and dairy, while the remaining 23% is used as cropland, the latter of which provides 82% of global calorie supply.

How is the Food Industry Responding?

From space saving, to developing new technologies, to waste reduction, here’s a run-down of the most interesting new agriculture developments.

1. Urban Farms

The notion of urban farming is not new. There are accounts of urban aqueducts being used in farming in Persia and water reuse in Machu Pichu, Peru, millennia ago. Allotments grew popular in major cities throughout the 20th century but now, as land becomes more precious, farmers have had to get more creative.

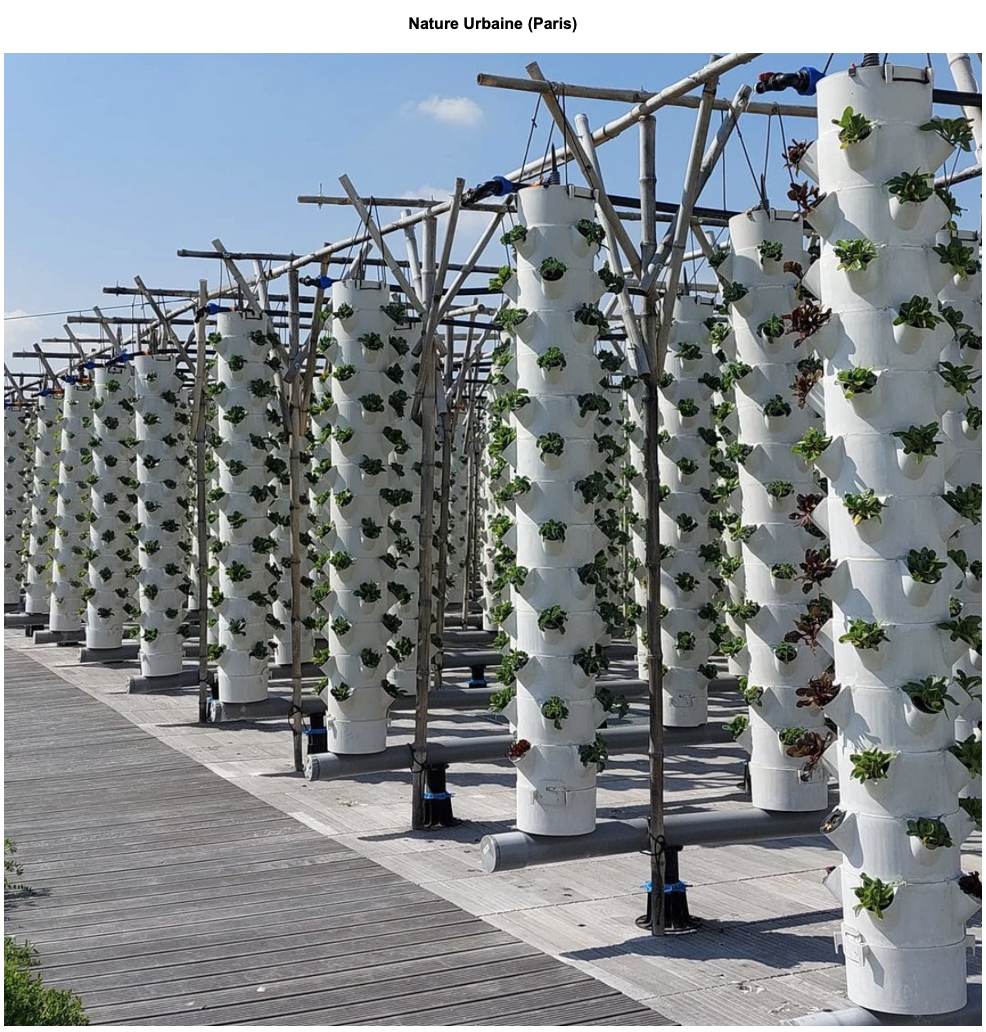

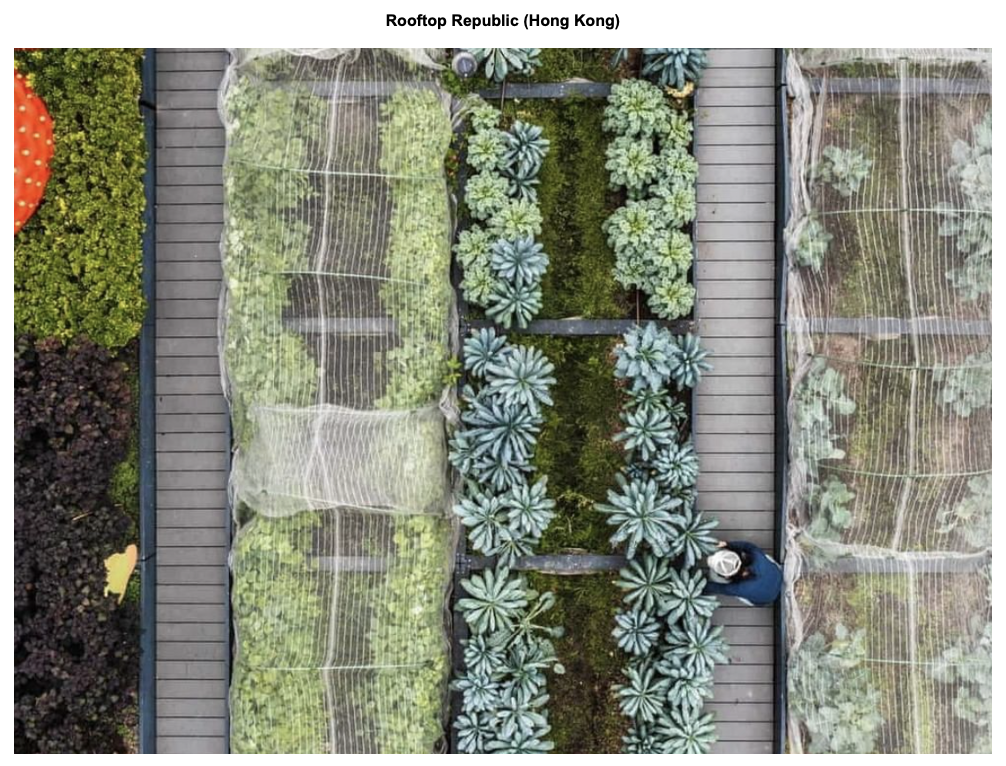

Rooftops, often dead spaces in large urban cores, are now being repurposed in places such as London, Paris and Hong Kong to house green, agricultural areas.

The solution allows growers to reduce environmental footprints by selling locally grown products and has a secondary environmental impact. Rooftop farms aid in cooling rooftops, which would otherwise absorb and radiate heat. This reduces energy usage and, ultimately, carbon emissions.

The world’s largest urban farm is Nature Urbaine in Paris’ 15th arrondissement, spanning 14,000 square meters. The farm has the capacity for harvest of 1,000kg of fruit and vegetables every day.

And, in bustling Hong Kong, farms have started appearing atop skyscrapers to inject some colour into the grey concrete skyline.

Urban farms also span London, all the way from Hounslow in the west to Mudchute Park in the east.

2. Vertical Farms

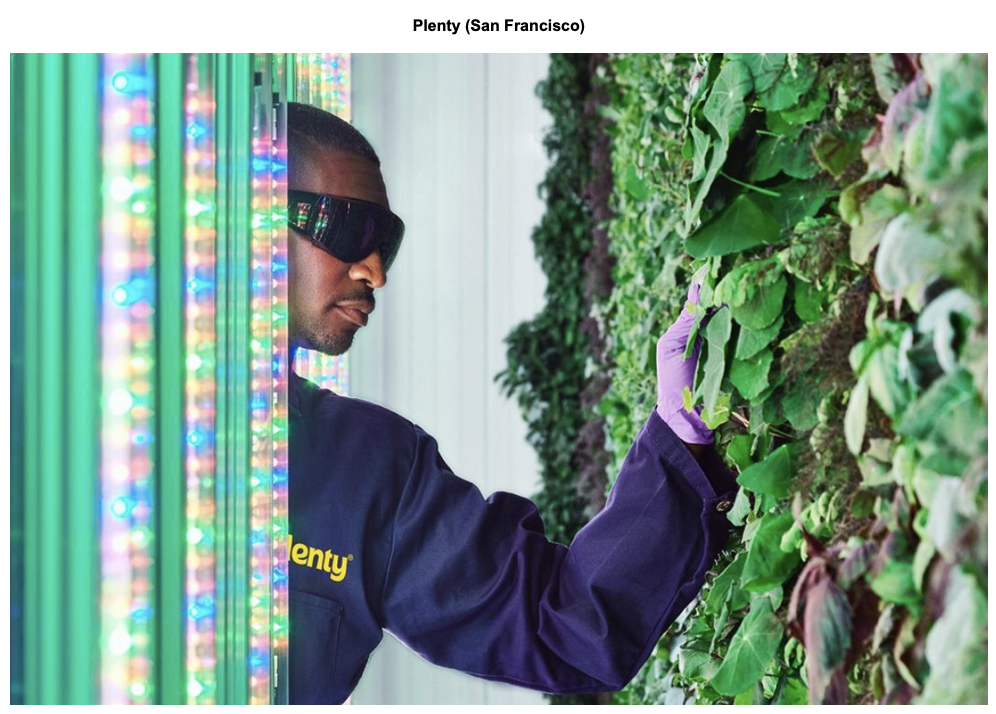

Another space saving technique is the use of vertical farms, which is a little more modern than urban farms.

The concept was developed in 1999 by a Public and Environmental Health professor at Colombia University. The idea is to use the dead space on top of an agricultural plot to stack fruit and vegetables, much like a high-rise block of flats.

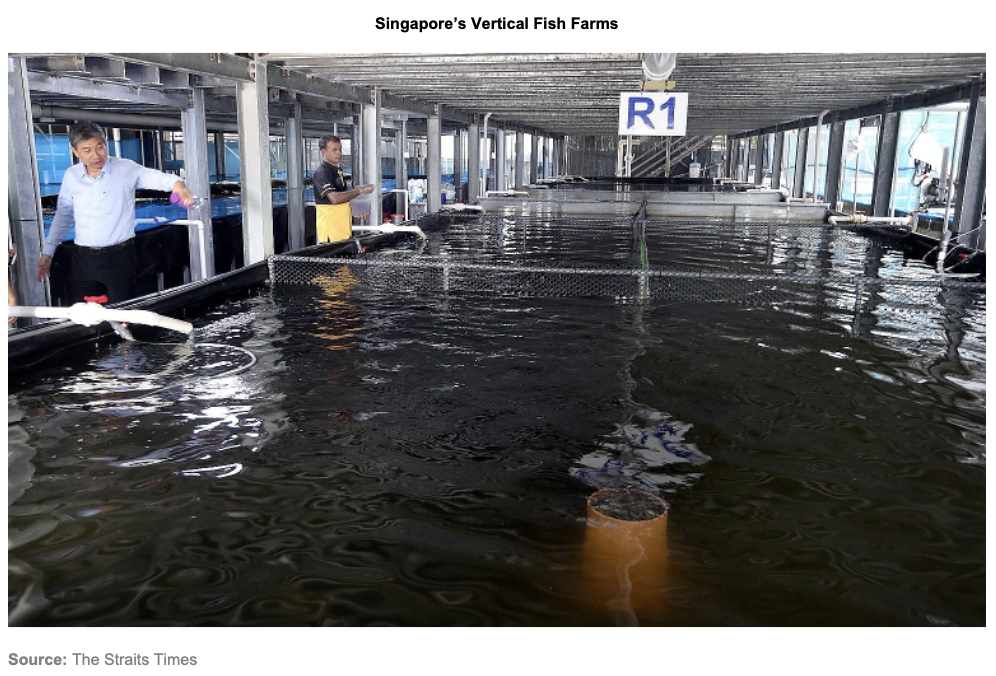

As of 2020, there are about 30 hectares of operating vertical farms in the world. In Singapore, Apollo Aquaculture Group has also established eight floors of vertical fish farms!

Not only do they save space, but the farms, which often incorporate specialized LED lights, have proven to increase yield significantly. One San Francisco start-up called Plenty claims its 2-acre farm can out-produce a 720-acre flat farm, while also using fewer natural resources such as water.

So, why aren’t we farming everything vertically? Well, the cost of starting up a vertical farm is much more expensive than traditional farming, given the initial outlay on technology and infrastructure. The energy demands of the LEDs are also significant, meaning vertical farms may not quite be viable on a wide scale right now. However, as they work to incorporate more green energy resources, this might change very soon. Watch this space!

3. Laboratory Grown Meat

Since the Impossible Burger and Beyond Burger burst onto the culinary scene, the world’s been shocked into the realization that we don’t always need to compromise on quality and flavour to eat plant-based meat alternatives.

After a steady increase in popularity, Beyond Meat went public in 2019, making $240 million during the IPO and now Impossible Foods is rumoured to be going public soon with a $10 billion valuation.

Since then, efforts have gone beyond plant-based alternatives that taste remarkably like meat to developing a different way to cultivate meat.

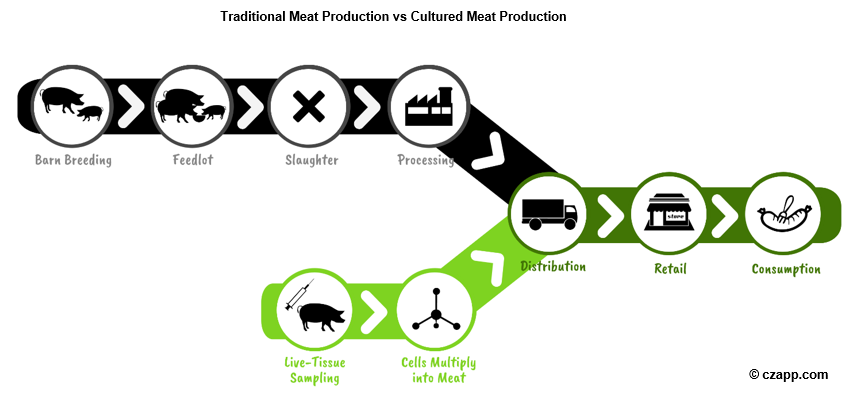

Using cells, scientists have been perfecting the process of growing meat in labs, meaning no slaughter and no huge agricultural footprint.

About $350 million was invested in the cultured meat space in 2020 and dozens of new companies were founded. And people seem to have no qualms about eating meat grown in a bioreactor – with a recent study indicating that 80% of people from the UK and US would be open to consuming it.

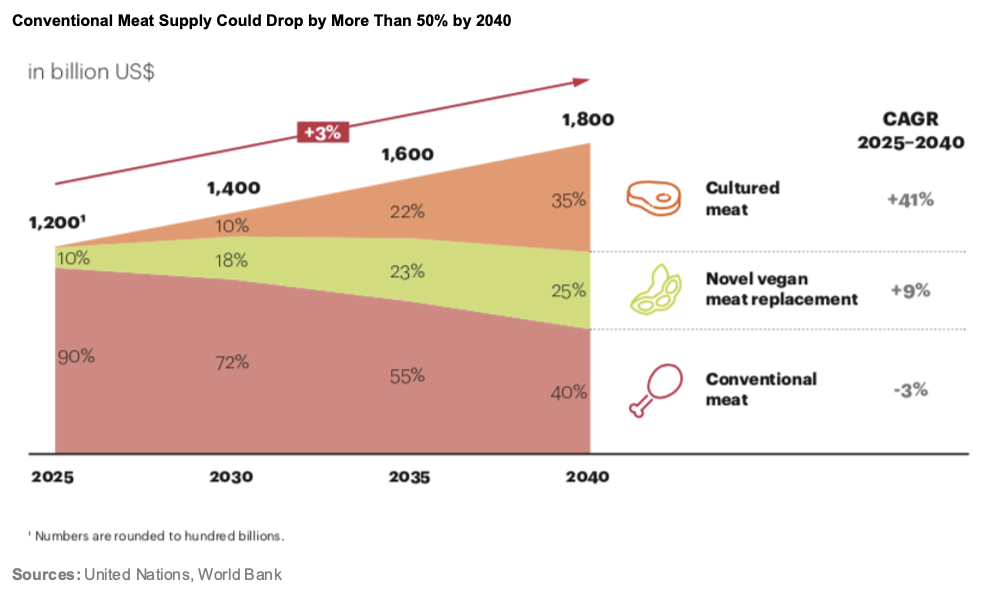

Although still just a fraction of the $1.4 trillion global meat industry, the plant-based meat and dairy industry should reach $75 billion in the next five years. Major companies, such as Nestlé, are also getting involved. The group is reportedly working with Israeli cell-based start-up, Future Meat Technologies, to develop a way to blend cultured meat with plant-based ingredients. Singapore-based, Eat Just, became the first company to obtain regulatory approval to sell its cultured meat last year.

One of the main issues with cellular agriculture is the cost, but some progress has been made.

Future Meat Technologies has managed to reduce the cost of 100g of its chicken to $4 and it plans to halve this price by 2022. Aleph Farms, another Israeli start-up has said lab-grown meat products will reach price parity with conventional meat quicker than plant-based alternatives.

Another issue holding back the cultured meat industry is intellectual property. The practice requires a cell culture, and these are stuck behind patents. Until these are publicly available, it’s tricky to see how cultured meat manufacturing can take place on the scale necessary to compete with or even replace traditional meat.

4. The Circular Economy

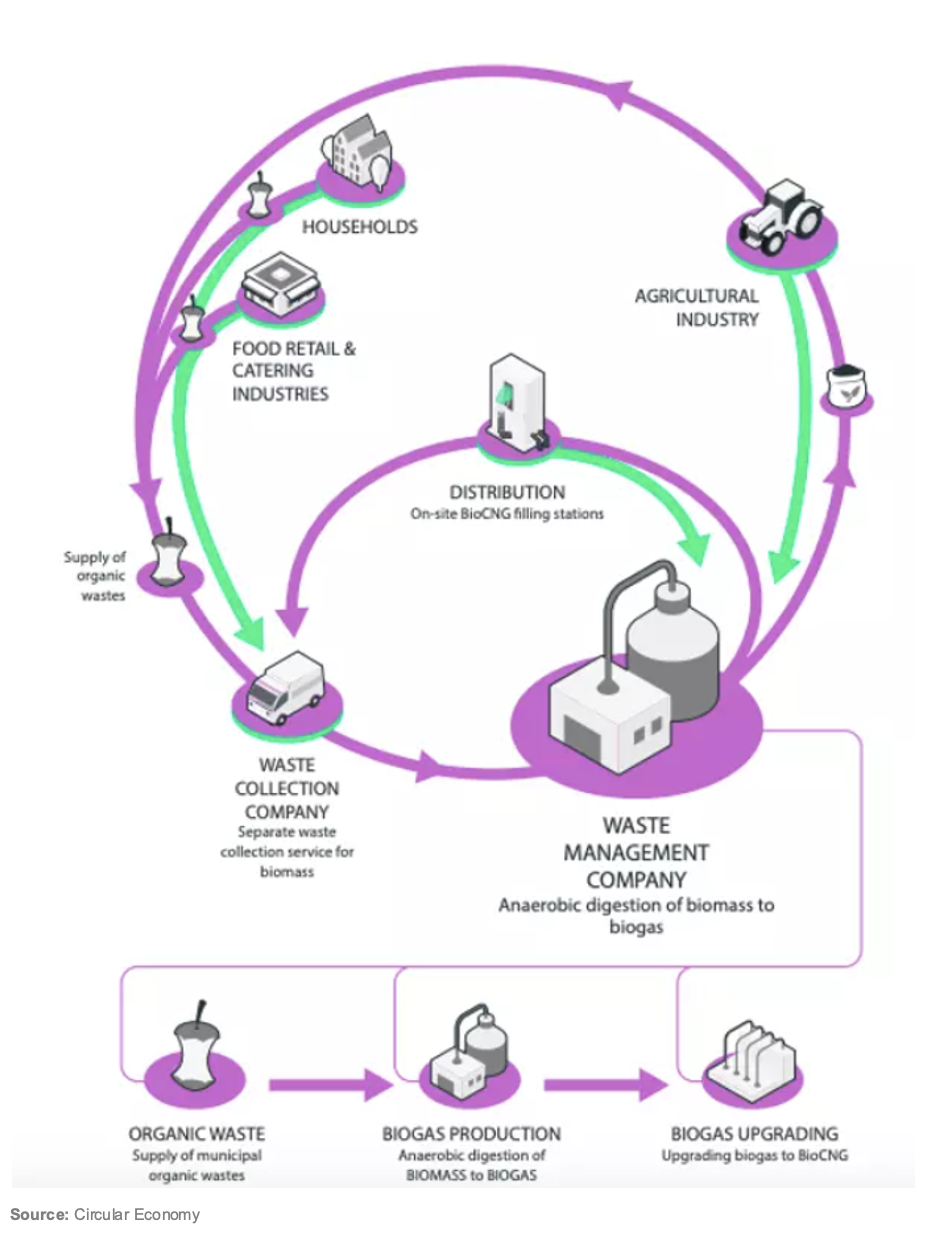

One of the biggest questions in agriculture right now is how to save or generate more space. Playing into this is the notion of waste reduction and the circular economy. The European Commission developed the AgroCycle program between 2016 and 2019 to promote the conversion of agricultural waste into valuable production chains across wine, olive oil, horticulture, fruit, grassland, swine, dairy, and poultry.

The city of Prague in the Czech Republic has mastered the art of the circular economy. The city’s authorities heavily promote the notion of “buy only what you eat” and huge emphasis is placed on household and agricultural waste recycling. As a result, it’s possible to send the majority of food waste to a waste management company, which then produces biogas from biomass. This biogas is used to power the waste collection trucks, reducing pollutants at the same time as food waste is reduced.

Other examples of tapping into the circular economy include the Feel the Peel juice bar, developed by Italian design firm Carlo Ratti and energy company, Eni. The system provides freshly squeezed orange juice, and the cups are made from bioplastic derived from the leftover orange peels.

While this may all still be a little out of the reach of the average consumer, there are ways everyone can get involved in waste reduction and the circular economy. Food apps Too Good to Go and Karma offer consumers the chance to buy food from retail outlets and restaurants at the end of the day before it is thrown away. The food is sold at a discount but offers the business an attractive alternative to throwing the food away and receiving no payment for it. Win-win!

5. Software, Automation and AI

Automation and digitalization already very much exist in agriculture. However, like in many other industries, technology’s developing further every day to create greater efficiency.

One major issue the food industry is facing is the dwindling bee population: the pollinators of our food.

Researchers are now conducting experiments using drones to simulate bee pollination, aiding the yellow and black army of food producers.

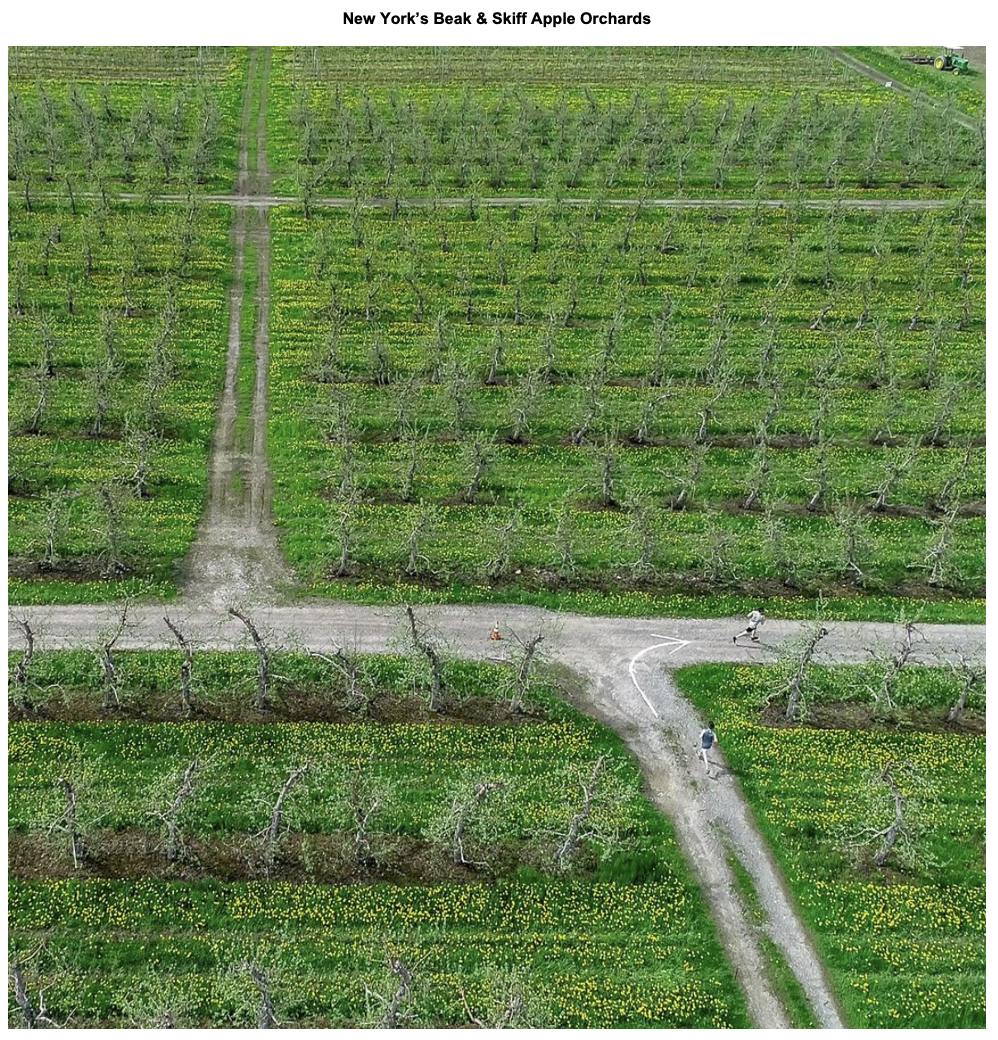

New York’s Beak & Skiff apple orchard became the first in the world to pollinate its trees with drones.

Precision farming is a technique that optimizes soil productivity and therefore increases yields by employing a series of measures. These include simple solutions such as covering crops, as well as more complex ideas such as soil mapping.

The premise of soil mapping is to maximize productivity by planting complementary crops side by side. This should reduce water and pesticide use as soil builds up nutrients.

A number of technologies are required for precision farming, including sensors, drones and satellite crop monitoring software. And, just like Google and Tesla are developing self-driving cars, a company called Smart Ag is testing self-driving AutoCart tractors to reduce the workload for farmers. Farmers in China are also using AI to detect diseases in crops and keep track of livestock health and location.

The next step will be the application of blockchain technology to create greater transparency across supply chains. But as more facets of agriculture plug into the Internet of Things, blockchain’s applications could even be extended to track machinery to flag when maintenance is needed.

In a world that demands excess and demands it quickly, farmers need to ensure they’re maintaining the pace. Several factors can disrupt the delicate crop ecosystem and jeopardize an entire harvest. Farmers in Brazil are currently grappling with the impact of frosts on cane fields.

One potential solution for this is gene editing, whereby desirable traits such as heat, cold or herbicide tolerance are introduced into crops.

Gene editing can modify crops to require less water or yield more. The technology, known at CRISPR, can also genetically edit livestock to reduce methane emissions.

According to the World Economic Forum, about 70% of agricultural methane and the majority of human-induced methane emissions come from enteric fermentation in the stomachs of cows and other grazing animals. If this can be reduced, the environmental footprint of meat cultivation could drop dramatically.

The quandary surrounding gene editing surrounds the fact it’s a relatively new technology, and the data’s not yet available to show the long-term impacts of modifying the genetics in a given ecosystem.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- Asian Sugar Consumption Hit by COVID and Slow Population Growth

- New UK Sugar Taxes: Will They Really Work?

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…