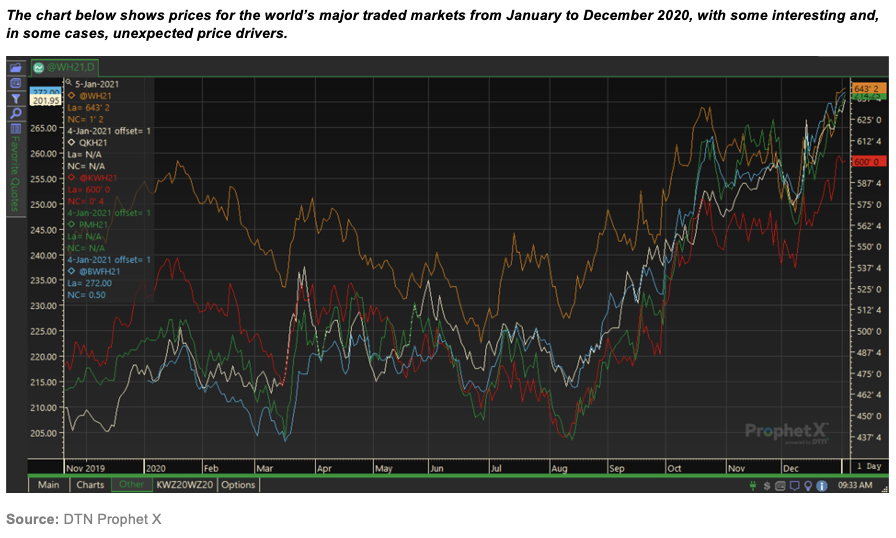

- 2020 was a year like no other for wheat, with huge harvest variations and demand unknowns.

- We saw record global wheat stocks yet a rising market in the latter half of the year, and the COVID-19 pandemic provided both demand and logistical uncertainties.

- Here, we look back on 2020 and uncover how the wheat market was impacted by the many unprecedented events.

The Major Price Trends of 2020

The New Year 2020 came in following a strong finish to prices in 2019.

Europe had also experienced terrible weather as farmers attempted to sow acres for the 2020 harvest. Estimates for EU production varied widely, while exports were up 50% year-on-year.

The Black Sea area had seen the Ukrainian export programme ramping up to 15m tonnes of a total exportable surplus of 19-20m tonnes between July and December 2019.

Russia, with fewer imports from a reduced crop in Kazakhstan, was reportedly increasing exports to Iran, adding yet more fuel to the bull argument.

A further price driver came from the US’ lowest wheat acreage since records began over 100 years ago!

Argentina, as an important exporter, saw farmers’ crops too dry when they needed rain and too wet when they needed the drying sun. Crop estimates were dwindling…

China entered 2020 following the hog herd destruction of the African Swine Fever, buying up pork supplies in every corner of the planet they could. This, coupled with the political back drop of the continuing US/China trade war, drove demand bulls’ hopes up.

In short, crops were looking precarious, estimates were sometimes difficult to judge, prices looked bullish and global politics added further uncertainty.

The Early Months of 2020

The early months of 2020 saw some cracks in the bulls’ armour as prices began to run out of steam towards the end of January.

The first report of a new virus, COVID-19, began to grab media attention in the middle of January as Wuhan was locked down on the 23rd. This prompted commodity markets to plummet.

The first thoughts were that an escalating virus threat might lead to demand destruction as people were potentially restricted in some areas. Clearly, no one was really considering these lockdowns in the Western democracies?! Nonetheless, the virus threat asserted a bearish factor to the wheat markets during the early months of 2020.

Russia saw growing 2020 wheat crop estimates, ranging from 83-87m tonnes, up from 73.5m tonnes in 2019.

India was chanting a record wheat crop expectation of 106m tonnes ahead of its harvest beginning in March and April.

Australia finally started to see some rain and fair amounts of it. The drought looked as though it was going to be assigned to history and a rebound for the as yet unplanted 2020 wheat harvest lay the foundations for hopes of a large crop.

Add Russia and OPEC’s disagreement in oil production to the COVID lockdown in Wuhan and you have the catalysts for a collapse in oil and general commodity prices, reflected in the bearish tone to the wheat market seen during January and February.

March 2020

The month of March 2020 is a time that few will forget.

We saw more lockdown restrictions implemented across the globe and the media showcased supermarket shelves stripped of the bare essentials. In this time, wheat prices rocketed as food security concerns emerged. And as we mentioned at the time, the consumer buys, so the processor buys, so the state buys, so the traders buy (etc)…all pushing prices up.

As the lockdowns created a wave of fear in governments, workforce and logistical worries emerged, especially for importing countries. How do they ensure food security for their people in a period of global lockdown?

Ports started to develop large backlogs of ships as port workers either threatened strike action due to the risk of infection from ship crews or were absent from work due to infection and the subsequent isolation requirements.

Logistics became a real concern, to the point that Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, amended their buying terms to push any logistical risk back onto the sellers.

April to the End of June

Here, we saw a calming of the price waters.

As panic buying died down and a return to business as usual on the demand side resurfaced, the markets looked more to the longer-term supply and demand numbers.

May’s USDA WASDE Release, in the first estimates for 2020/21, put global production up from 764m tonnes in 2019 to 768m tonnes in 2020. World ending stock projections were raised from 295m tonnes in 2019/20 to a huge 310m tonnes in 2020/21.

Despite smaller 2020 wheat harvest predictions in Europe, Ukraine and the US, prices were pressured by the large projected stocks with thoughts of much larger crops in Russia, Australia and Argentina.

We mentioned at this time that ‘stability’ was not a word for the 2020 wheat market. This would ring true as the year ticked on.

The Latter Half of 2020

More bulls entered the market pits.

July and August saw ups and downs, as the market struggled to get a handle on the Northern Hemisphere harvest sizes while the combines rolled.

As August ticked on and harvests wound down, the bulls started to drive the market upwards – a trend which has continued, despite a few stumbles, right into 2021.

This rise may well be due to 2020 having become a venture into the unknown with COVID-19 impacting the lives of all. Food security, whether on an individual consumer level or on a national level, has become a significantly more prominent factor for many.

Wheat prices have been driven up, despite record global wheat stocks at 316.50m tonnes in 2020/21, up from 300.62m tonnes in 2019/20.

In 2020/21, China and India, the two most populous countries in the world, hold nearly 60% of all the global wheat ending stocks at 155.32m tonnes and 31.11m tonnes respectively. Food security has long been on the Governments’ agendas here. These stocks will not see external markets in 2021.

Look a little deeper into the major exporters of the world and we see a diminishing stock level, with just 59.99m tonnes in 2020/21 vs. 67.89m tonnes in 2018/19.

Russia began looking at wheat export quotas for 2021, which were put into effect in November, only to be replaced by the highly requested export taxes for wheat, as internal prices continued to rise. These most definitely contributed to the price strength of wheat as 2020 drew to a close.

Europe saw extremely unusual harvest variations between 2019 and 2020 (154.51m tonnes vs. 135.80m tonnes). 2021 is still much debated, but we have seen, even in the most climatically stable wheat producers, signs of potential uncertainty to come.

A growing need for ample stocks for each and every nation that can afford this luxury has become, and may well remain, of underlying importance as we move into 2021 and beyond. It therefore comes as less of a surprise to reflect on the latter months’ price rises of 2020 than the headline figure of record stocks might at first suggest.

Lessons for the Future from the 2020 Wheat Market

- COVID-19 hit the world in a manner unexpected by virtually all.

- Food security has become ever more important to countries with people to feed.

- Record stocks may not always be where they are needed and may not be available to the wider marketplace.

- Regional lockdowns with the potential for shipping and logistical disruption may change the historically robust global supply-chain.

- Weather in Europe and Australia, among others, has shown that there can be no complacency as huge variations in wheat harvests become potentially more common in the years to come.

- Russia has recently demonstrated the need to curb internal prices and how that impacts the global market price.

Records are there to be broken, but pandemics and climate change around the world will ensure that at the start of 2021 we continue our venture into the unknown.

Happy New Year!

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…