Insight Focus

- Jet A needs to have certain characteristics to be classified as SAF.

- But what happens when new feedstocks are being developed?

- Certain processes need to be followed to ensure the fuel’s properties remain the same.

Welcome back to Czapp’s series on SAF.

Last time round we tried to clarify what SAF is and this week we are looking at the specifications for SAF. The specifications define what the fuel is, what it can do and what the user can expect from the fuel.

Why Specifications Matter

The specifications include big stuff from how much energy the fuel contains (think aircraft range) to other aspects like its appearance – perhaps less important but nevertheless an essential detail.

While the subject of fuel specifications may seem dry and esoteric, they are vital. They provide the blueprint to guide the fuel manufacturers in building their fuels. They dictate what is allowed, what isn’t and the limits of certain properties.

Historically, Jet A-1 was made by conventional refining of crude oil, then later by Sasol’s Fischer-Tropsch coal-derived process. The key point to note was, despite this change in feedstock and processing, the properties of the final product were unchanged.

Some of the properties of Jet A-1 may have been altered by the new components, but the final blend was within the published limits and so met the requirements of the specification. The essential target of the many recent, current and future changes is that the final product is unchanged and so aircraft operability is unaffected.

But how can you introduce significant changes to feedstock and processing and yet end up with the same product? With care, which is exercised through the design and application of specifications.

How to Modify Fuels

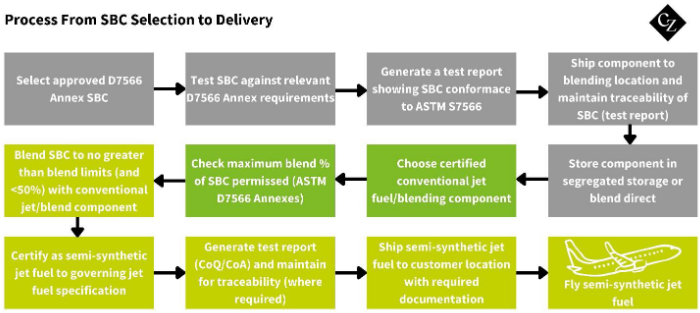

The first lever of control over the final quality is through a specification called ASTM D7566. These rules govern the non-conventional synthetic blending components (SBCs).

D7566 does three things:

- It describes the technical pathways that may be used to produce an SBC (there are currently eight).

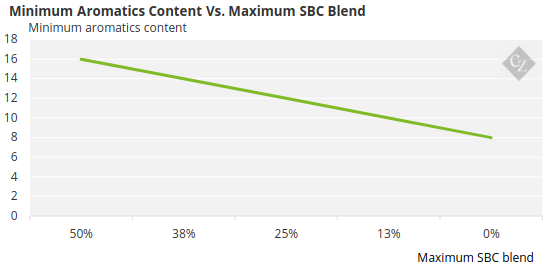

- It details the composition limits of the SBC in Jet A-1 (most are 50%, some 10%, depending on the properties of the SBC)

- It describes the extra checks that are required to ensure that any particular SBC property does not take the SAF blend outside the specification limits.

Particular attention is paid to aromatics compounds, density and boiling ranges, as these properties represent the biggest differences between Jet A-1 and SBCs.

So, if you are making SAF and add an SBC according to D7566, you must make sure the checks are all within limits. Only then will the SAF blend meet the D1655 specification.

What Can Be Added?

So, how do you get an SBC included in D7566? Through a third specification called D4054.

Any new novel processing pathway (for instance a new agri-waste feedstock or a new catalyst) must be reviewed by the D4054 committee and industry stakeholders. These stakeholders can include manufacturers, airframers or regulatory authorities.

After lengthy and painstaking scrutiny (or using a fast-track process that carries a 10% blend limit penalty), a successful outcome means a candidate is accepted into D7566.

So, we’ve identified what SAF is and how it is regulated by specifications. Next time we will look at the technical pathways – and their strengths and weaknesses.