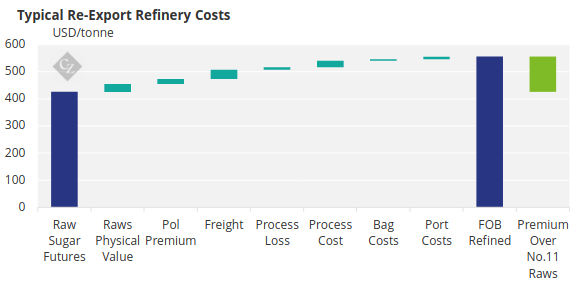

Re-export refiners play a crucial role in the global sugar market as important swing producers. Their profitability, however, is heavily influenced by freight and energy costs. In this explainer, we delve into the workings of re-export refiners and their impact on the sugar market.

For decades almost all sugar was made at the site where cane was crushed or beet was sliced. The final food-grade sugar was then shipped around the world.

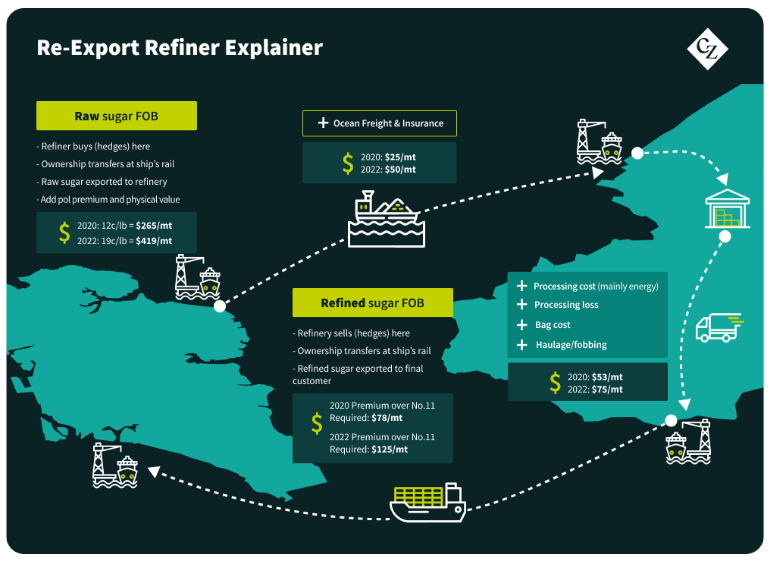

However, the development of high-quality raw sugar from major producers like Brazil and Australia opened new possibilities. This raw sugar could be shipped directly in the ship’s hold to a refiner abroad as an industrial material. The overseas refinery could then process the raw sugar into food-grade refined sugar and sell this domestically or abroad. If the sugar was sold abroad the refinery was operating as a toll, or re-export, refinery.

The resulting refined sugar could then outcompete refined sugar from local/annexed refiners if the raw sugar freight and local energy costs for processing were cheap enough.

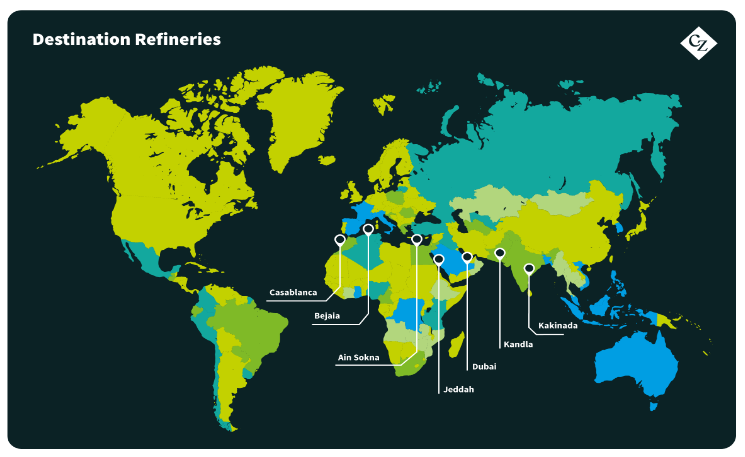

The toll refining sector started to grow strongly in the mid-1990s following the opening of the Al-Khaleej Sugar refinery in Dubai in 1995. It now accounts for around half of global refined sugar trade.

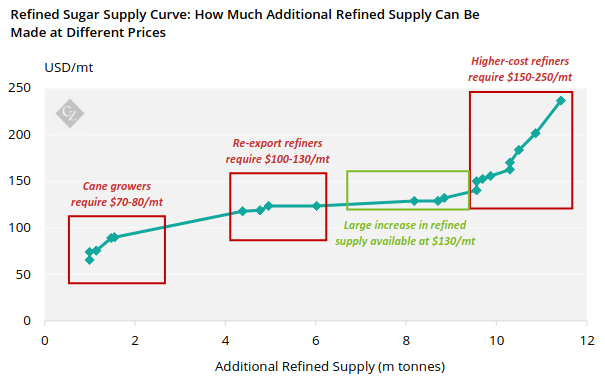

The sector is a swing producer, ramping up production when the white sugar market provides a big enough return over the raw sugar market and reducing throughput if the returns are not high enough. Although destination refineries have higher production costs than local refineries, they are also usually placed close to areas of strong sugar consumption growth, notably in North Africa and the Indian Ocean region.

Re-export refiners also have shorter supply chains to regional end-consumers than local/annexed refiners do and so can benefit through flexibility and immediacy of sugar supply.

The premium the white sugar market pays over the raw sugar market doesn’t have to be limited to the futures markets. Many of the world’s re-export refiners can also command strong regional physical premiums over the refined futures, which often reflect the cost of refined sugar made at origin.