Insight Focus

- The sugar market is suffering from a decade of underinvestment in production.

- Global sugar consumption continues to trend higher – as food and fuel.

- High world market gas prices will make cane bagasse increasingly valuable.

Presentation Outline: What Happened in 2022; What’s Next in 2023?

Let’s start with a bit of context: what happened to sugar in 2022. We can then look at the prospects for 2023 with fresh eyes.

While sugar prices have gone nowhere in 2022, there’s been plenty going on:

In 2023 we will need to grapple with stagnant global sugar production and increasing sucrose consumption, as food or as ethanol for fuel. This might be enough to help sugar break higher at some point in the next 12 months.

2022: Going Nowhere

It’s every analyst’s nightmare. 15 months of the market chopping sideways and going nowhere at all. Everyone thinks you’re joking when you reply “sideways” to their demand for a directional view.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

It’s even more unfortunate given what happened in the years prior. Raw sugar more than doubled off the covid low of 9c/lb, helped by physical buying from refiners and futures buying from speculators.

The range has been wide: from around 17.50c to 21c. At the top of the range we’ve seen pretty comprehensive producer hedging emerge, starting around 19c and then increasing in intensity as we move higher. This has given raw sugar producers 6 opportunities to hedge above 20c in the past 18 months.

At the low end of the range we risk losing Indian supply, which needs around 18c to be workable. Chinese refiners and other big buyers have also been good at picking up sugar sub-18c. There have been two major, sustained dips below 18c for the buyers.

This means it’s been a good year for sugar producers and consumers. Everyone has had the opportunity to hedge well if they’ve followed a disciplined risk management plan.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

As I mentioned at the start, 2022 has been a wild year. The big story for all markets has been the strength of the US Dollar.

In 2020 and 2021 Central Banks flooded the world with cheap money on an unprecedented scale. In 2020 they had to do this to keep economies alive during the pandemic. But by 2021 we had learnt how to live better with covid. People were starting to be vaccinated, businesses and world trade were resuming quickly.

By the middle of 2021 the US Dollar had reversed course and was strengthening, at first quite slowly. The markets were starting to worry about inflation and US bond yields had also started to rise.

Most people didn’t really notice and it was only when inflation became headline news at the start of this year that the Dollar accelerated further. Central Banks quickly reversed course by raising interest rates.

All other things being equal, a stronger dollar is negative for commodity prices. Higher interest rates stifle global trade.

In this context, sugar staying in a sideways range in 2022 has been an excellent result. As we move into the end of this year the strength of the Dollar has faded and we’ve dropped back towards where we would have been if we’d taken the lower path. All other things being equal, this is better news for commodities, and might enable those with a good fundamental story to strengthen at some point in the future.

For now, no-one has a very good idea about the value of money, which is still bad for trade which relies on credit and access to cheap money. But as long as the Dollar stabilizes at or near current levels for a bit, we might have a bit of room for some further commodity strength.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

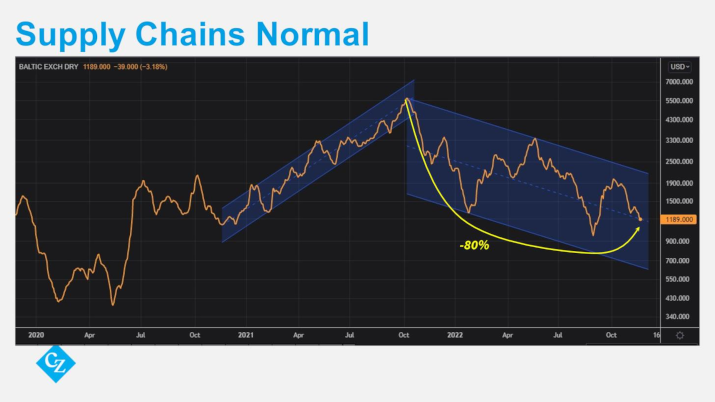

It’s also important to briefly mention that the world’s supply chain problems have resolved.

During the peak of covid, much of the world’s trade stopped temporarily. When things started to re-open, trade resumed and pent-up demand for goods meant that existing shipping capacity wasn’t sufficient. Problems emerged everywhere, made worse by periodic continued covid lockdowns, notably at Chinese ports.

But now, inventories of goods around the world are huge and the increased interest rates have made consumers more wary. Demand has fallen, which has been really negative for freight rates. In short, it’s not a great environment for many commodities today.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

You can see this in the way that many commodities have traded recently. This chart shows a retail ETF which tracks various commodity futures.

It may seem like commodities are still positive, especially given the news flow in 2022 but many have traded sideways for most of the year. Basically, the 2020 and 2021 commodity bull market is long over, no-one really knows what’s coming next.

This is good news for us because it means that rather than needing to be a covid expert, or an energy expert, or a forex export in 2023, we can refocus on sugar itself.

2023: Upside Potential?

I’ve spoken about poor demand for goods and high inventories, so perhaps a good place to start is sugar consumption.

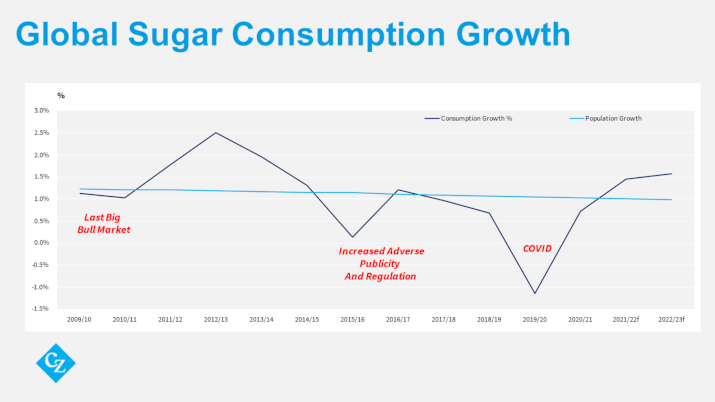

At the start of the century, the formula for global sugar consumption was easy. In a normal year, sugar consumption around the world grew at 2%; 1% for population growth and 1% for increasing wealth.

In very wealthy countries sugar prices don’t really affect sugar consumption. Most people in America or Australia don’t know how much a kilo of sugar costs because it’s so cheap relative to other foods. Besides, in these countries most sugar is consumed in processed foods and drinks, not tabletop.

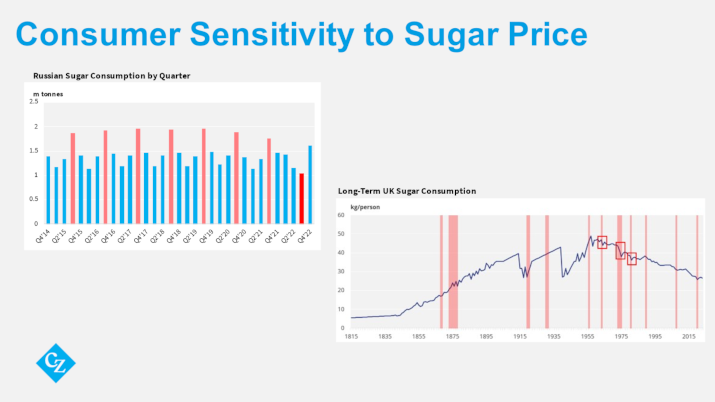

But we know that for most countries in the world, especially where a high proportion of income is spent on food and most food is made at home, consumers are sensitive to price.

You can see in this chart that as we went through the last sugar bull market in 2009-2011 and prices went to 36c/lb, per capita sugar consumption didn’t grow; sugar consumption only grew at 1% in those years. As prices fell in the middle of the decade, we got back on track at 2% a year.

But something changed around 2014. We’ve seen increased consumer awareness of the amount of sugar they eat in many countries, supported by increased regulation in places like Mexico, Chile, the UK, and South Africa.

Then we’ve had the major decline in sugar consumption thanks to covid lockdowns, which disrupted out of home consumption in many parts of the world in 2020 and 2021. It’s socially acceptable to drink a litre of cola if you’re watching a movie in a cinema in the evening, but not if you’re at home watching Netflix.

Nowadays sugar consumption only grows in line with population globally. In many mature economies, it’s actually declining.

This sounds negative, but it gets a bit worse, I’m afraid.

Sugar prices are more than double where they were 2 years ago, and this does affect sugar consumption in some countries. Let’s look at Russia, which is the chart at the top left. Sugar consumption has been pretty consistent for most of the past decade. Peak consumption happens in the hot summer months in Q3 each year, highlighted in red.

Q3’21 was the first Q3 where you could see a possible impact from higher sugar prices, in this case driven by a poorer than expected beet crop which led Russia to import raw and white sugar from the world market.

You can really see the impact on prices this year. Sugar consumption in Q3’22 was awful; partly because panic buying in Q1’22 at the same time as the invasion of Ukraine may have brought some demand forward, but also because Russian prices reached more than $1,000/mt.

It’ll be the same for many countries around the world. Consumers will be super-sensitive to price and also to risks of unavailability.

Meanwhile in the UK sugar consumption peaked in the 1960s and has been in long decline ever since. World market sugar prices don’t really seem to influence UK sugar consumption very much.

I’ve marked recessions in red on this chart and the most you can say is that they sometimes accelerate the downward trend in consumption temporarily, but sugar consumption is also robust and it normally rebounds back to the old trend once the recession ends.

Given we are about to start 2023 with sugar prices close to 20c, I think this means the consumption outlook for sugar in the year is poor. We should expect 1% growth worldwide at best.

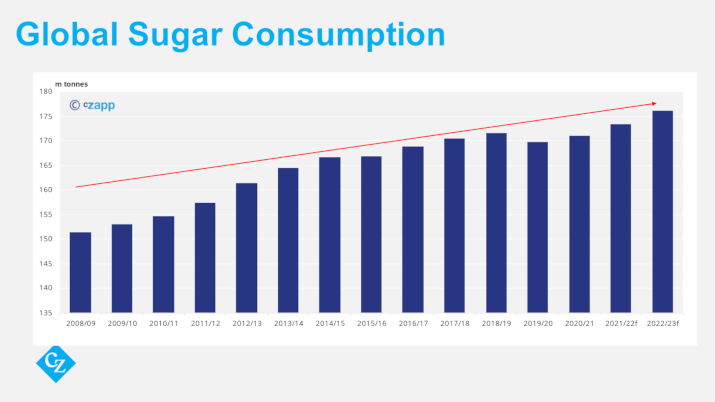

Let’s see what these percentages mean. Sugar consumption has continued to grow since 2008. You can see how it levels off a little in 2014. You can see how it actually falls as COVID hits. But even with only 1% growth, it continues to march higher all the time, and in 2023 we will exceed 175m tonnes of sugar eaten around the world for the very first time. This 175m tonne number is important, so please remember it and I’ll revisit in a few moments.

But quickly, beforehand, it’s worth remembering that sugar isn’t only eaten. The sucrose in cane and beet can be used to make ethanol as a road fuel, and this demand is growing strongly too.

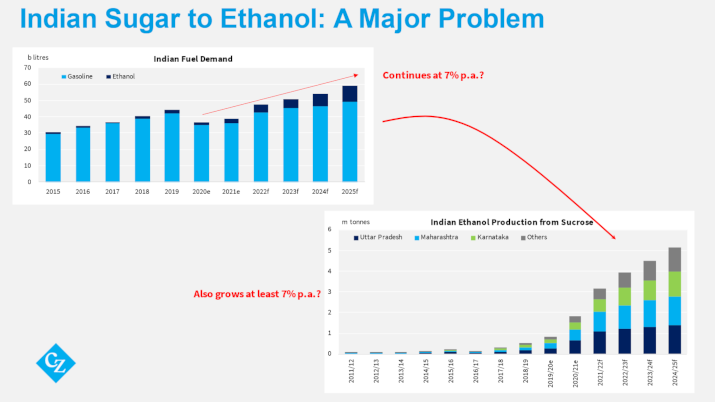

The major growth in ethanol currently is in India, and it’s reshaping the sugar market.

If you want to know where sucrose consumption growth is in the coming years, it’s in India and it’s going into motorbike engines. Indian gasoline demand was growing at around 7% a year before COVID, almost entirely driven by the 2-wheeler sector.

India has decided it will reach a 20% blend of ethanol in gasoline by 2025. If gasoline consumption continues to grow at 7% a year post-COVID, then this means that Indian ethanol demand will also grow at 7% a year. This rate of growth means demand doubles every decade. Where will all this ethanol come from?

Originally the government gave incentives for new distilleries to be built and intended around half of the ethanol would be made from distilling some of its grains stockpiles and half from its excess sugar cane. But the rise in grains prices after the invasion of Ukraine has meant that India has sold almost all of its excess grains and will want to keep what’s left to ensure food security.

This means that grains distillation is lagging and sugar cane is likely to be used in greater amounts to make the ethanol. More and more cane juice and molasses will be used to make ethanol, not sugar.

At the moment, Indian cane acreage and yields have improved fast enough to mean there’s enough sucrose to make ethanol and enough sugar for domestic needs and export.

But the world sugar market has already more than doubled in the past 2 years when India has exported more than 20m tonnes sugar to the world market. What happens if there’s a poor cane crop? This is a very major problem for the world sugar market. The last major bull market in 2010 and 2011 was caused by Indian cane crop failure. We are building the same problem into the market once more.

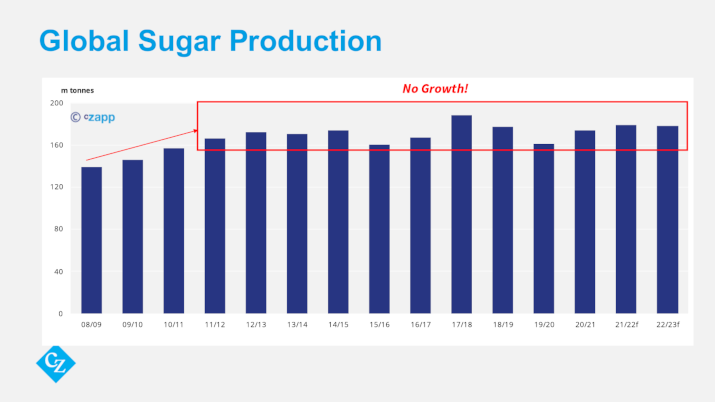

This is important because sugar production around the world isn’t growing. It hasn’t grown for a decade.

Remember the magic figure earlier – that the world will consume 175m tonnes of sugar this year? That’s roughly how much sugar the world has made each year for more than a decade. We’ve been at 175m tonnes plus or minus 15m tonnes for more than 10 years.

This means that if we have a good year and we end up with 175m tonnes of sugar production, then the world market will remain well-supplied.

But if we have a poor year and we end up making less than 175m tonnes sugar, stocks will need to be drawn down somewhere. Prices will probably need to rise. We are one poor crop in a major sugar-producing region from having a supply problem.

Let’s look in a bit more detail at some of these major sugar producing regions to understand why they aren’t growing.

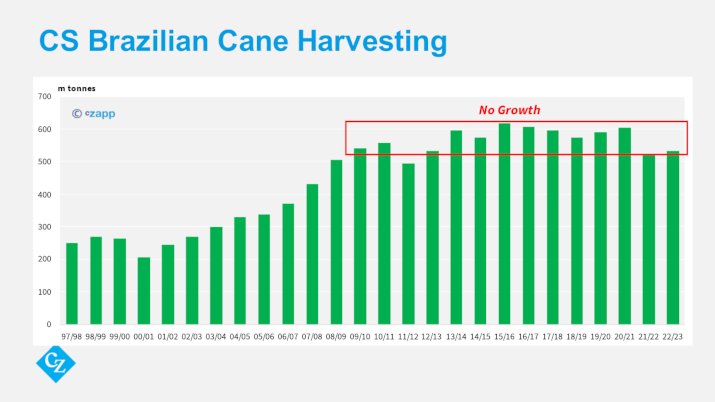

All discussions around sugar production tend to start in Centre-South Brazil, the world’s largest cane growing region and sugar exporting region.

Cane growing and harvesting here hasn’t grown in a decade. The Brazilian cane sector expanded rapidly in the early 2000s, fuelled by international debt but this was stopped by the 2008 financial crisis. Since this time we’ve seen mill closures, industry consolidation, and gradually the milling sector has been reducing its debt burden down towards what most banks would consider an acceptable level.

But we’ve still not seen any new greenfield mills for a decade. Even today, it’s better for mills to de-bottleneck their own operations, pay down debt or acquire other mills than it is to develop a new mill or cane area. Worse, while sugar returns are now good for the mills, ethanol returns have been depressed by government changes to fuel taxes made in response to high inflation. Sugar, which is only half of their business, has to support the whole sector.

The problem now is getting to the point where mills here will invest in new cane fields and new cane crushing capacity.

Building a new mill and growing a new cane field is a long-term commitment. These are major, capital intensive projects. A cane mill takes at least two years to build from initial planning to ribbon-cutting. Cane fields take at least three years to reach full productivity. Investors need to be as confident as possible that they will make a return deep into the future.

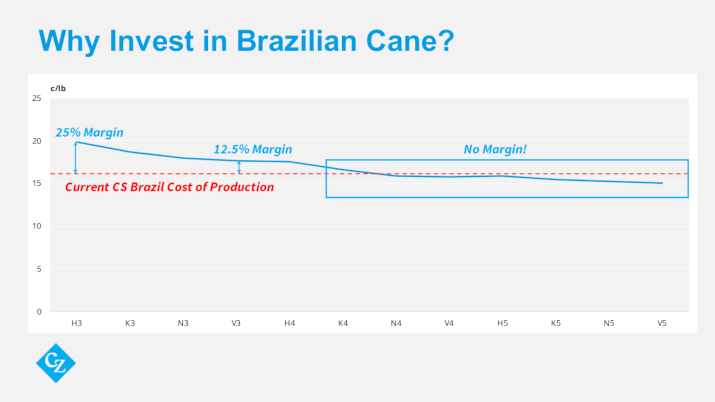

Currently, we think that cost of sugar production in CS Brazil is around 16c/lb. At first glance, with the sugar market at around 20c/lb, it looks like the market is paying a 25% premium to cost of production. But investing is a long-term decision so we need to consider the whole futures curve, not just the front month. The curve is backwardated, and here’s a problem.

Prices at the end of 2023 are only 12% above cost of production. If you consider that the local benchmark interest rate in Brazil is nearly 14%, then new sugar projects don’t offer potential investors any premium at all over local government debt. For 2024 and beyond, sugar prices don’t offer any margin at all.

No-one will invest in new capacity in Brazil with prices at this level. There’s no return on offer. The sector will instead spend money debottlenecking – installing new modern boilers, optimizing cane harvesting patterns, etc.

If we want to see new sugar production in CS Brazil – already one of the cheapest places to make sugar and the place with the very best sugar export logistics already in place, we need the whole futures curve to be above 20c, which implies the front of the curve needs to be higher still.

If not Brazil, how about India?

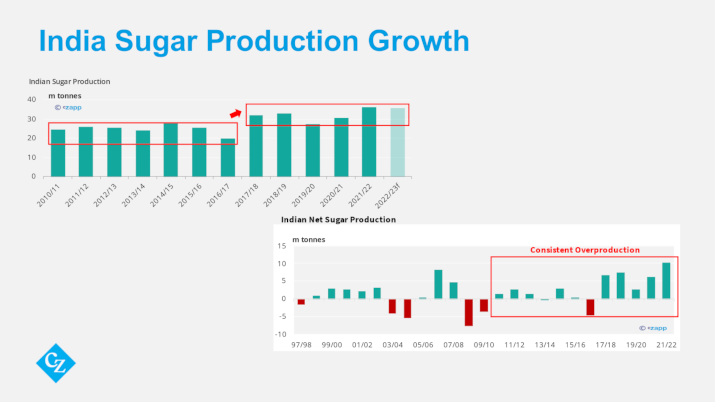

In recent years its overtaken CS Brazil as the world’s largest sugar-producing region, helped in part by government incentives to grow the ethanol industry. Sugar production definitely has grown; whereas in the early part of the last decade India consistently made 25-30m tonnes sugar, it’s recently adjusted to making 30-35m tonnes sugar.

The big question is whether this can continue; will India jump to making 35m-40m tonnes sugar and also increase its ethanol production? The milling capacity is certainly available. I question whether the land is. India has no fresh land available for farming. If cane keeps expanding it will come at the expense of other crops, perhaps cotton in the south, perhaps grains elsewhere.

The other problem is that cane is a thirsty crop and it’s already grown in the most suitable areas. As cane area expands, it does so into increasingly marginal land. This is fine while water availability is high. But during years of lower water availability, this cane planted on marginal land won’t perform well. Perhaps this means we will see more variability in Indian sugar production in the future than we’ve had for much of the last decade.

It’s going to be dangerous for the world market to continue to depend on India, whose government will always prioritise its own food and energy security over exports and is not afraid to intervene.

The other major sugar producers around the world aren’t growing either. A decade of falling sugar prices between 2010 and 2020 meant the whole sector has been starved of investment. Prices doubling in the past two years is welcome, but it’ll take time to repair the damage, and in many cases the prices of crops that compete with sugar cane and beet have also risen.

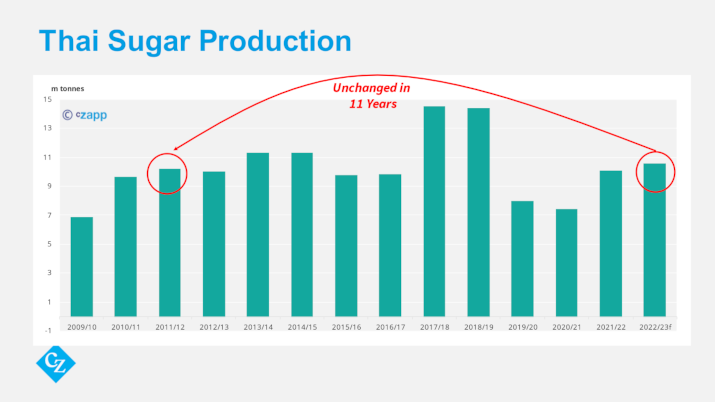

Here’s Thailand, a major raw and white sugar exporter. Sugar production has been as high as 14m tonnes in good years, but right now it’s no better than it was 11 years ago. Cassava returns are at the same level as cane returns and both are low maintenance crops. Farmers don’t yet have an incentive to increase cane area with prices at 20c.

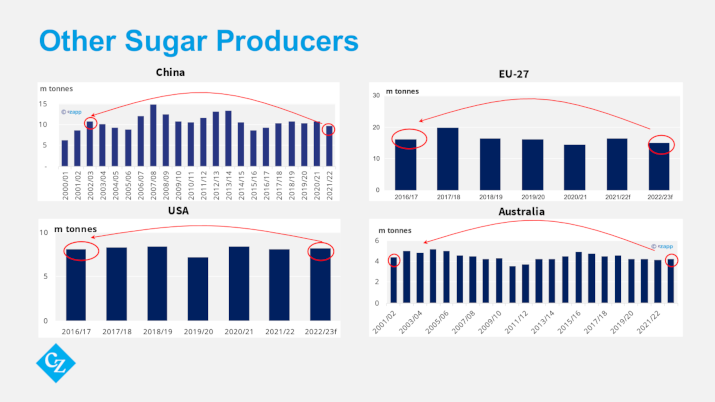

Chinese sugar production is at the same level it was 20 years ago. European and American sugar production is stagnant, which I guess at least is good news for those countries who can export to them. Australian sugar production hasn’t grown in 20 years. I could continue but hopefully you can understand the problem.

Sugar consumption keeps growing. Ethanol from cane is a further booster. Production isn’t growing at all. This can’t continue.

It’s only a question of time before sugar prices start to rise once more.

I think at some point in 2023 sugar will need to break out of its sideways range to the upside.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

I’ve spent the entire presentation talking about raw sugar. What about the refined sugar market.

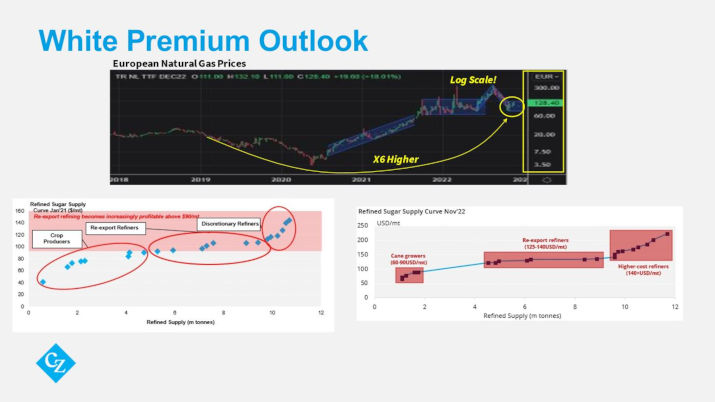

One of the major changes for the refined market has been the increased cost of energy in 2022, notably natural gas. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has meant that Russian flows of gas to Europe have decreased. Europe is now a major buyer of world market LNG cargoes, competing against traditional buyers like Japan and Pakistan. LNG prices are high around the world, and this means increased costs for any major refiner who buys energy on a spot or short-term basis.

This means that cane mills who use bagasse to make sugar, especially refined sugar, are at a huge advantage over refiners who use other energy sources. These mills should focus on maximising refined sugar output and should also invest in upgrading to higher pressure boilers, installing bagasse dryers and perhaps consider pelletising excess bagasse for sale. We can help: if you’re interested please contact cmcgrath@czarnikow.com.

It also means that in order to attract increasing supply of refined sugar onto the world market, higher prices are needed. In early 2021, we needed refined prices (futures plus physical premiums) to be around $100/mt over raw sugar futures to source 10m tonnes global refined sugar supply. To attract the same supply today requires $130/mt. For as long as global sugar consumption holds near 1% a year and global LNG prices remain elevated, the white premium will continue to hold above $100/mt.