- This week newswires carried stories that Cuba wouldn’t export sugar in 2023

- Cuba won’t make enough sugar to meet its own consumption needs for the first time in more than 200 years.

- How did one of the world’s most famous sugar cane growers get to this point?

The Mathematics of Decline

One of my oldest friends works in asset management. He once complained to his wife about an under-performing investment. She replied, “Don’t worry, darling, it can’t keep halving forever.”

He replied, “An investment that’s lost 90% is one that had fallen by 80% and then halved.”

This gloomy tale is one that could easily apply to the last 30 years of the Cuban sugar industry.

The Early 1900s: Interdependence with the USA

Cuba emerged as a major sugarcane-grower in the 1800s. Global sugar consumption was starting to rise, the climate was perfect for cane cultivation and in time the island established significant commercial relations with the United States of America.

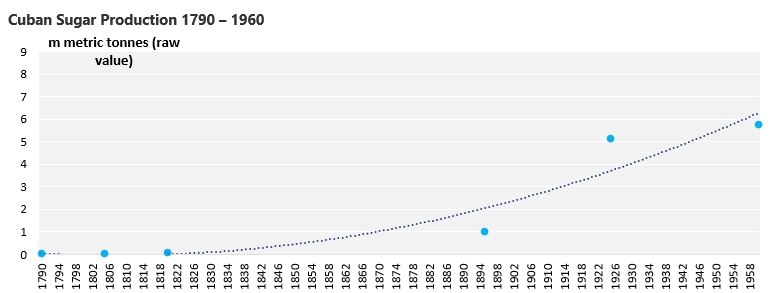

Cuba’s sugar production rose from 14k tonnes in 1790 to 1m tonnes by 1895. Cuba gained its independence from Spain in 1898 and by the start of the 20th century it was the largest sugar producer in the world, with most of the crop being exported.

In the first half of the 1900s the USA was responsible for almost all the foreign inward investment in the Cuban sugar industry and American companies owned many of the mills, vertically integrating them with their own sugar refineries in the United States. Cuba enjoyed a large preferential sugar quota into the USA.

The Cuban Revolution & Alignment with the Soviet Union

Everything changed after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Sugar mills were expropriated and nationalized.

At first, the Castro regime attempted to diversify the Cuban economy away from sugar and to industrialise. This led to severe labour shortages for sugar cane harvests. From 1962 the USA placed Cuba under a comprehensive trade embargo, removing America as a destination for Cuban sugar and restricting the import of machinery for cane mills and fuels.

Cuba therefore became more closely integrated with the Soviet Union. At first, a long-term trade agreement was signed in 1964 to export 24m tonnes sugar at 6.11c/lb between 1965 and 1970. In return, the Soviet Union shipped fuels and machinery to Cuba.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

In 1972 Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) and negotiated a new long-term trade agreement with the Soviet Union whereby sugar would be sold at 11c/lb, a 2c premium to the prevailing world market price. In return Cuba received Soviet oil and gas at below-market rates. This deal meant Cuba missed the major raw sugar price rallies in the early 1970s and early 1980s but was sheltered from low sugar prices in the late 1970s and most of the 1980s, as well as the energy crises of the 1970s.

The Collapse of the Soviet Union (and the Start of the Decline of Sugar)

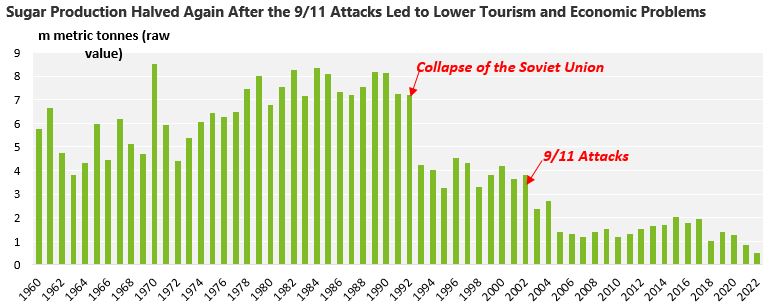

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 changed everything. From this time, Cuban sugar was sold to the Former Soviet Union at world market prices. At the start of 1992 world market sugar prices were around 8.50c/lb.

The effect of lower prices on the Cuban industry was catastrophic. Under the Soviet trade deal, farmers and mills had no incentive to modernize or become more efficient and they were now exposed. At first the industry tried to hide the problems through the widespread practice of cutting immature cane in the ‘wrong’ season to try to hit current year cane targets. This came at the cost of lower cane production in the following year. Cuban sugar production halved from around 7m tonnes (raw value) in the early 1990s to 3.4m mtrv in 1994/95. In 1990, Cuba accounted for 30% of global sugar exports. By 1994 this had fallen to 14%.

The government implemented measures designed to stem the widespread economic decline, breaking up many state farms into smaller, more autonomous cooperative units. However, cane was still purchased by mills based on weight, not sucrose content, with minimal bonuses offered for exceeding tonnages outlined in annual plans. Farms were not incentivized to outperform.

From 1994, western trade houses extended financing to the Cuban sugar industry for the first time in decades, almost entirely as pre-crop finance. However, this didn’t lead to a noticeable improvement in sugar production: fertilizer and herbicide application was still too low, machinery remained in a poor state and fuel shortages persisted. Western involvement then waned from 1996 after the passage of America’s Helms-Burton Act, which threatened foreign companies with penalties if they dealt with properties that had been nationalized during the Cuban revolution.

Cuba Pivots to Tourism; Sugar Industry Restructures

In 1997, tourism replaced sugar as Cuba’s largestindustry, ending more than a century of sugar’s dominance. But the September 11th terrorist attacks on the USA in 2001 led to further problems for the sugar industry. Tourism revenue collapsed, Venezuela suspended oil shipments to Cuba after it failed to make payments and prices for goods in Cuba were raised to preserve foreign exchange. With the country facing economic hardship, the government announced the permanent closure of 71 of its 156 sugar mills to improve the industry’s performance. A further 40 mills were shut in 2005.

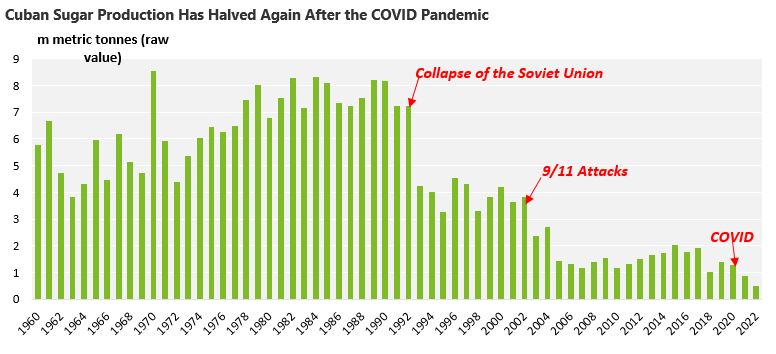

For much of the last 15 years, Cuban sugar production has limped along at 1.5-2m tonnes a year, meeting domestic consumption and allowing export of raw sugar to China (~400k tonnes a year under bilateral agreement), the EU (69k tonnes a year under the CXL quota) and the world market. But the country’s dependence on tourism was again its undoing.

COVID Hits Tourism

The global COVID pandemic from 2020 led to a huge fall in tourist numbers, decimating foreign exchange earnings.

This has now led to further collapse of the sugar industry as machinery, fuel, fertilizer and other field inputs became scarce. The 2021/22 harvest was the first in more than 200 years that was unable to meet Cuba’s own domestic sugar consumption needs. It seems likely that for the first time since the early 1800s, Cuba won’t export sugar at all in 2023.

From a peak of 8.5m tonnes sugar production in 1969/70, output has fallen by 95%. “Don’t worry, darling, it can’t keep halving forever.”