Insight Focus

- Smaller shipments in H1 and sluggish farmer selling favour exports in Q4.

- 2021-22 crop failure in Brazil, strong crush, lackluster Chinese demand limit expectations.

Despite the leading role that inflation and fears of recession have recently played in creating the risk aversion which have weighed on the soybean market over the last few weeks, the weather’s impact on US new-crop yields as well as speculation about Brazil’s ability to cover anypotential gap in the international market if the US crop fails and exports falter in the fourth quarter are about to upstage them.

Although it is still too early to talk about a crop failure (US soybeans don’t fill their pods until August, and this year the crop was planted later than normal), the 2022-23 supply and demand balance is tight due to a planted area that is smaller than previously forecast.

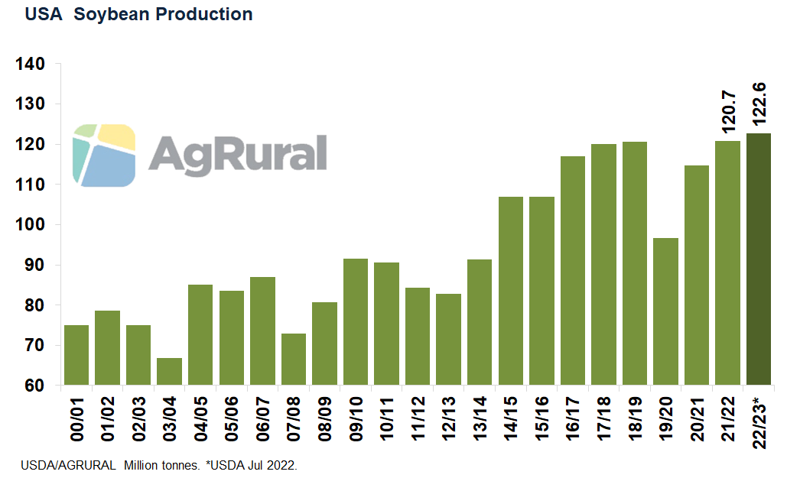

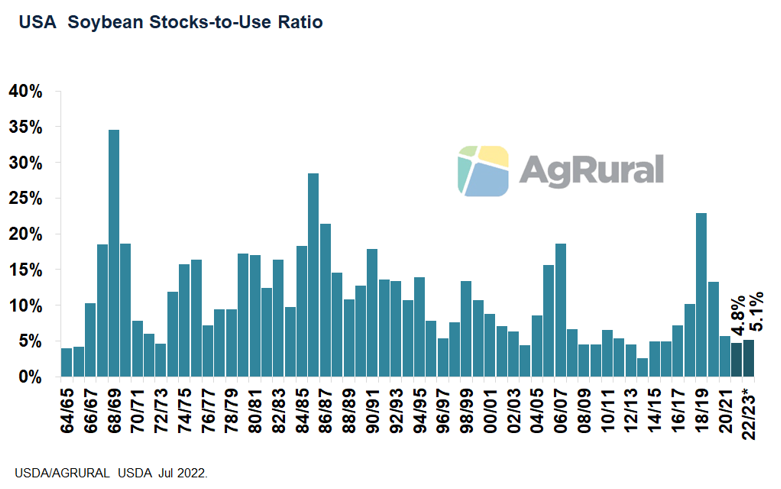

On 30 June, the USDA cut the 2022-23 soybean acreage estimate from 36.8m hectares reported on Mar 31 to 35.7m – just under half a million hectares above the area sown last year. As a result, production is seen now at 122.6m tonnes, down from 126.3m forecasted earlier in the year. Even after cutting exports and domestic use, the USDA reduced the 2022-23 projected ending stocks to 6.3m tonnes, just above the tight estimate for 2021-22, which is 5.9m tonnes.

The projected stocks-to-use ratio for 2022-23 is just 5.1%, one of the lowest. That means that, if the planted area released on 30 June is correct (the USDA is resurveying states where the planting pace was behind schedule in June), the already tight supply and demand balance has little room for production losses. And production, of course, may fall from the latest estimate (which is based on trendline yields) if the weather does not cooperate for the remainder of July, a month that has been already drier than normal, and especially in August, during the pod-filling stage.

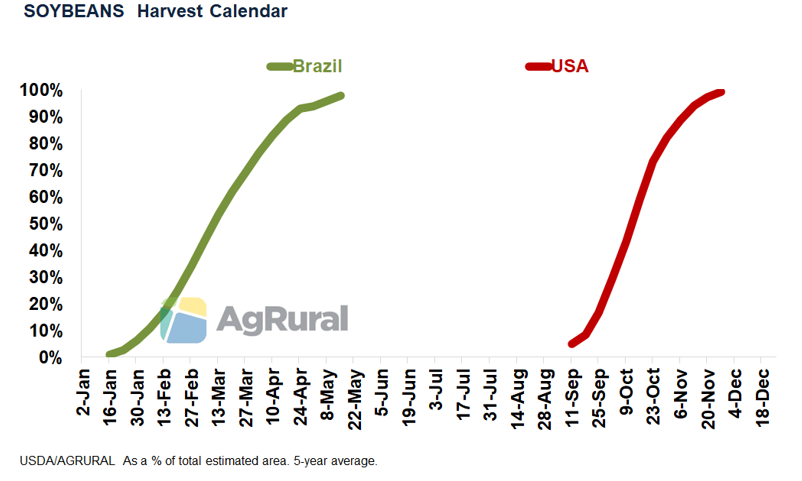

Complementary Crop Calendars

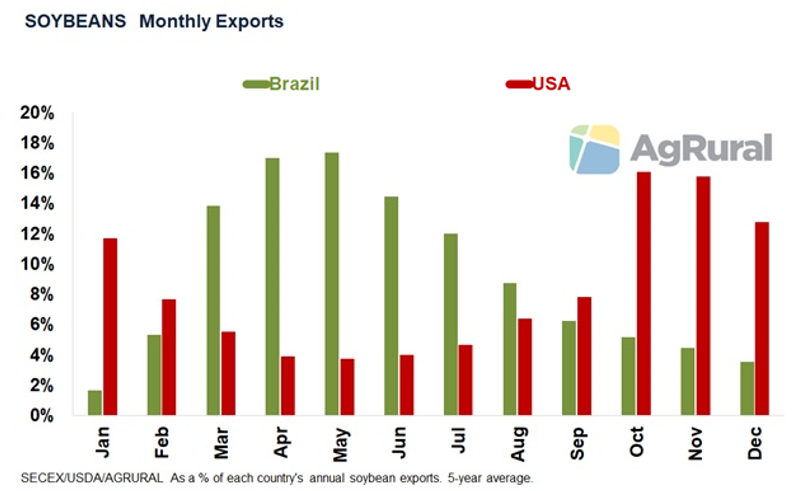

One of the many explanations for Brazil’s success in producing and exporting soybeans is the fact that it has a complementary crop calendar to that of the US, which until recently was the world’s largest producer and exporter. With its harvest concentrated between January and April, Brazil exports more soybeans in the first half of the year, while the US exports are mostly shipped in Q4, concomitantly with its harvest. Over the last five years, 75% of Brazilian soy shipments were made between March and July. In the US, 64% of soybean exports left the ports between September and January.

Due to the crop calendar, Brazilian soybean exports are less competitive in the Q4, when importers switch to more abundant and cheaper US beans. The concentration of Brazilian corn exports in the second half of the year also contributes to the loss of momentum in soybean shipments, as well as a greater appetite in the domestic market for soybeans that Brazilian producers are still holding on to by the end of the year, before the new crop harvest starts in January.

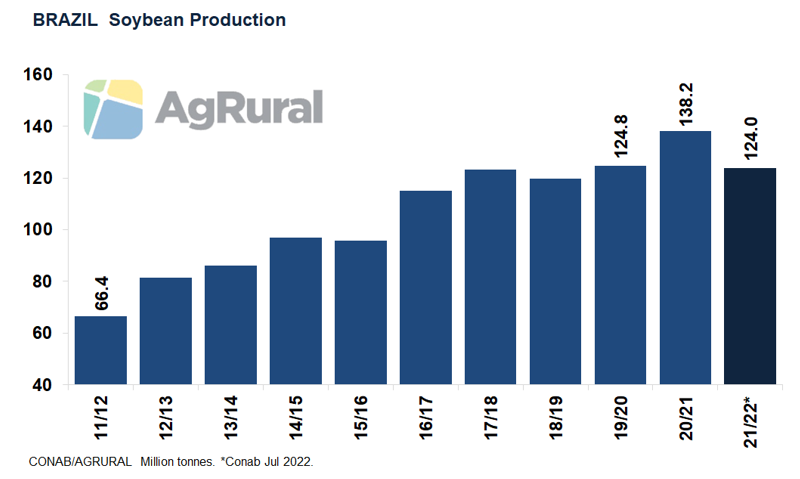

But crop failures in the US, with a resulting spike in soybean prices and the need for importers to reposition in the market, normally bolster international demand for Brazilian soybeans in Q4. With the 2022/23 supply and demand balance already so tight in early July, when the impact of the weather on soybean yields (for better and for worse) hasn’t happened yet, it is natural that doubts about Brazil’s ability to export at the end of the year arise earlier – even more so when Brazil had a crop failure itself in 2022, when Brazilian production dropped from a potential 145m tonnes to just124m.

Unusual Year

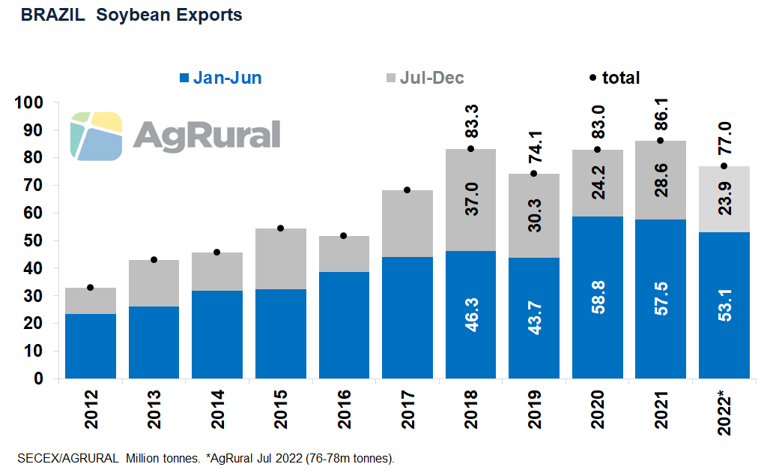

If 2022 were a typical year, Brazil would have few soybeans to export in Q4. But, as farmer selling is slower than normal and exports lost steam in H1, stronger Brazilian shipments at the end of the year cannot be ruled out if US exports are compromised by a crop failure and/or uncompetitive prices.

From January to June 2022, Brazil exported 53.1m tonnes of soybeans, compared with 57.5m a year earlier. China was the destination of 35.2m tonnes in the first six months of 2022, down from 39.8m tonnes a year earlier. If Brazilian 2022 exports really do hit 77m tonnes, as AgRural is forecasting, the country will ship 23.9m tonnes in H2, 4.7m less than a year earlier, but still a significant volume, considering that the crop failure caused by drought reduced production by about 20m tonnes.

Tight Stocks

If Brazil exports 77m tonnes in 2022 and domestic consumption is 51m tonnes (in line with last year and driven by a strong increase in soybean meal and oil exports, which offset a drop in domestic use), ending stocks will be just 1.6m tonnes. However, the possibility that production may have been a little higher than the 124m tonnes estimated by Conab cannot be ruled out. The USDA, for example, is expecting 126m.

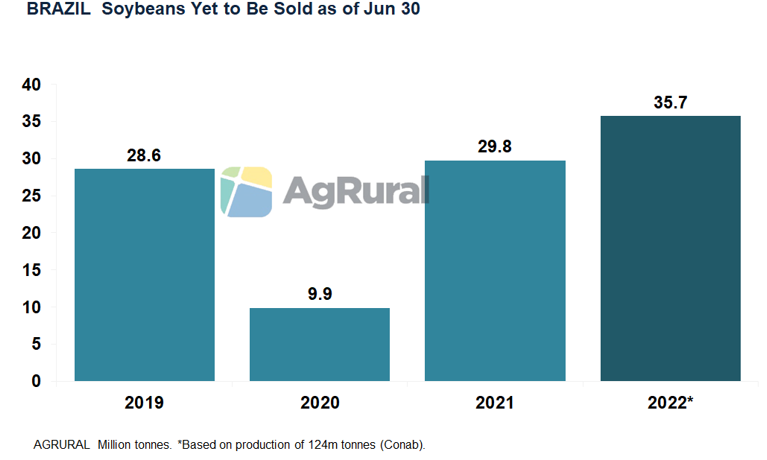

Another factor that gives Brazil some leeway to cover part of a potential reduction in the US exports in late 2022 is the sluggish pace of selling by farmers. Despite major progress in June, at the end of the month producers still had nearly 36m tonnes still to be sold. A year earlier, when production was higher, it was just under 30m tonnes but the farmers were quicker to sell,

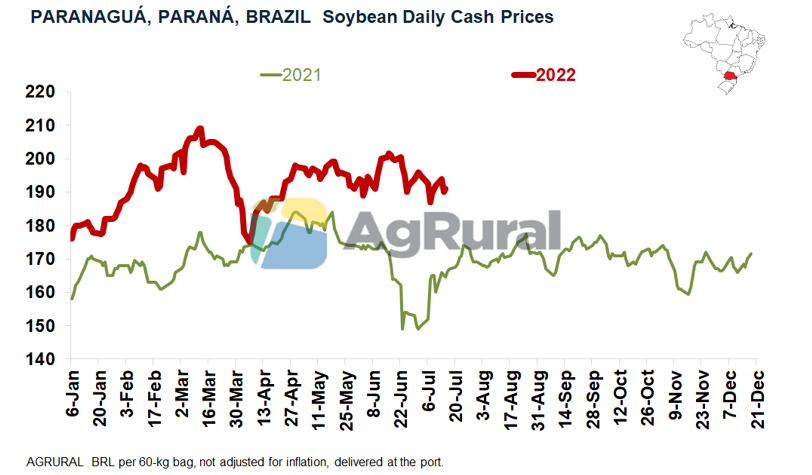

Prices Will Have to Go Up

To attract those soybeans from Brazilian farmers, however, buyers will have to bid higher. With the recent fall in prices caused by the macroeconomic-inspired correction in Chicago, producers have already drastically reduced the volumes offered, after selling around 8m tonnes in June. Capitalized and aware of the sharp rise in production costs for the next crop, they are holding on to their soybeans in anticipation of better prices in the coming months. Although Chinese demand has been sluggish and may limit the upside potential, they are betting on tight US supply to make their marketing strategy work.