Insight Focus

- Belize is home to great genetic diversity in vanilla

- Identifying and preserving genetic variants is key to vanilla industry’s survival

- There are many parallels between the cocoa, and vanilla industries

We sold our first vanilla last week to a Danish celebrity chef who specializes in roasting game. Since I neither speak Danish nor eat meat anymore, I’m not sure who he was; but we marked the date in our calendar as we have been planting shade trees and vanilla for about two years now.

Vanilla grows naturally here in Belize and there are many wild varieties all over Central and South America that are under threat from deforestation and illegal harvesting. Most, if not all of it, is not commercial grade. The only varieties permitted to be imported into the US under the Standard of Identity are vanilla planifolia and vanilla tahitiensis.

Lack of Genetic Diversity

There’s probably about three people in the world that can identify vanilla by variety by sight, and I’m definitely not one of them.

In 2019 we participated in a multi-country effort to have a large group of vanilla identified using DNA technology, led by the University of Florida. One of the most important findings for us was that Belize is home of one of the parents of V. tahitiensis and some never before seen V. planifolia variants, so we are heading back into the bush with Wildlife Collection Permits (and insect spray) for a little more ferreting around.

Why are we doing this? Mainly because we are very aware that if there is any disease problem with either planifolia or tahitiensis then the global industry is in jeopardy. Practically all vanilla is grown from cuttings, meaning it is genetically identical. The collection has to be done in Belize because it is home to great genetic diversity in vanilla. The Ministry of Agriculture has neither the resources nor the background to do this work and relies on people like us.

While being one of the most expensive commodities in the world, the vanilla industry is very poorly supported on research and breeding because, like cocoa, its mostly grown by people living in poverty in developing countries. Collaboration between different growing countries and research institutes, once considered unthinkable, is now beginning to develop. Developments in new genomic tools now allow variants to be identified much more cheaply, and that will help preserve them in-situ in protected areas, and ex-situ in gene banks like the one we are developing on our farm.

Buyers Seeking Sustainability, Reliability

In that vein we see a lot of parallels with the cocoa industry where there was not a lot of sharing of ideas and research until the last few years when the industry finally realized the locker and the bank account were empty. Like cocoa we do see a trend towards larger-scale production of vanilla in countries such as Indonesia, Uganda and towards an agroforestal model like ours in Central and South America.

With more scrutiny on practices on the ground around incursions into protected areas, living Income, good agricultural practices and sustainable development goals, buyers want to partner with operators on the ground who can protect their interests and reputation. They also want to work with sources that are not going to default on them if they can get a higher price elsewhere. There is no futures market or risk management mechanism in the vanilla market, so relationships and track record are paramount.

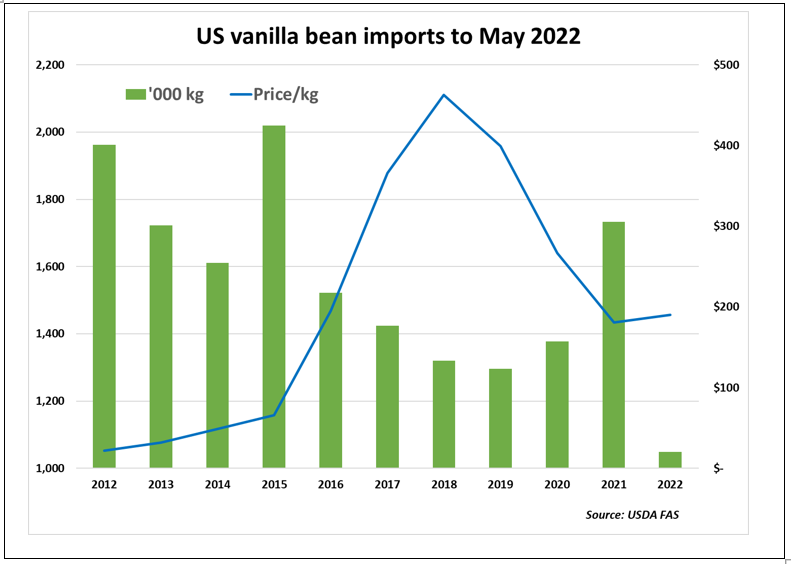

The benchmark the US industry uses is import data sourced from the US Department of Agriculture website (the US is around 30% of total global demand). Each month you can download shipments by origin and CIF US prices and we watch that closely. Regrettably, the data in the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation database is generally thought to be fairly unreliable.

In 2020, buyers scrambled for vanilla as demand soared due to a surge in home baking. However, prices did not move higher immediately due to a large crop in Madagascar, which overhung the market, as well as a predictable drop-off in demand as the world moved on to its new normal (although demand is higher than in pre-pandemic times). The 2021 crop in Madagascar is thought to be close to 3,000 tonnes from initial forecasts closer to 2,000 tonnes.

Boom and Bust

However, just to demonstrate the boom-and-bust nature of the vanilla market, prices in Madagascar are now below the government mandated minimum export price of USD 250 a kilogramme. However, the government has little in the way of enforcing this price being passed on to farmers, and in fact the only way they can officially manage that is by controlling who receives export licenses, which will happen in September, three months after the official start of the season.

News coming out of Madagascar is that the 2022 crop has been affected by drought and uneven flowering so prices may pick-up strongly.

Quality Issue

If price weren’t challenge enough, then quality is probably just as important. When prices are high, farmers harvest early, reducing vanillin content, and middlemen reduce curing time to be paid faster. Perversely, when prices are low, farmers also harvest early and middlemen reduce curing time so they can bet paid faster. This comes about because while the export price is supposed to be an official minimum price, the prices from farm to export warehouse are completely different and virtually unregulated.

Having traded a lot of sugar, cocoa and coffee in my time, I understand why international buyers look to other origins where price signals pass between all participants, relationships can be developed, and quality is part of the conversation. Ivory Coast and Ghana face the same challenges with cocoa.

Competition from Substitutes

The other challenge the whole vanilla industry faces is substitutes. Vanillin can be made from wood pulp and as a by-product of the oil industry. In fact, real vanilla grown on a vanilla plant is thought to be less than 1% of the global vanillin market. If the vanilla price goes too high, price-sensitive customers just substitute vanillin.

So, my last thought for you is next time you take off for your Caribbean holiday, don’t buy any of the vanilla extract you find at the airport. Most of it is vanillin from petrochemicals, and you have been conned. Buy the real stuff – just a little – you will be amazed!

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…