Insight Focus

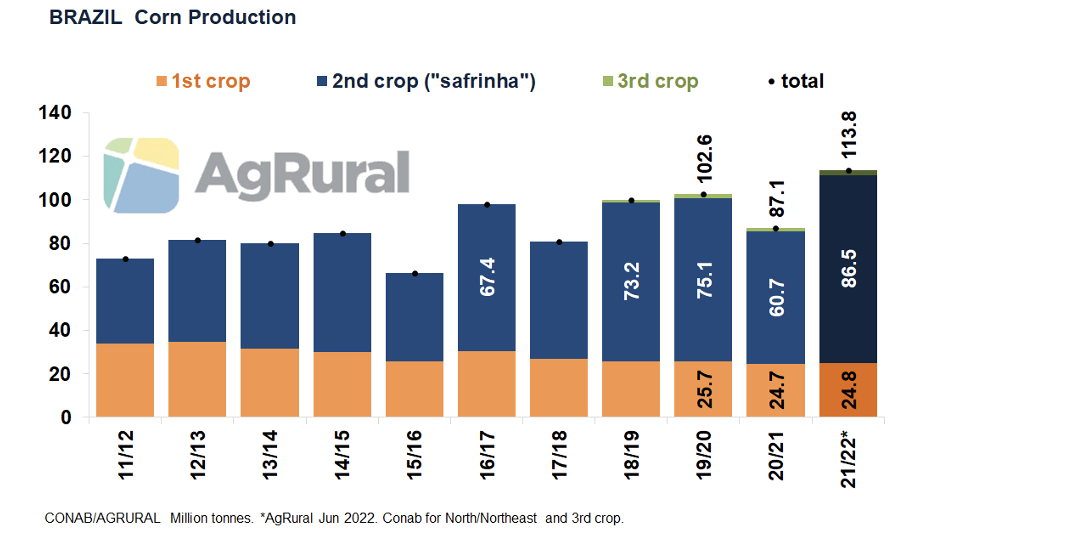

• Despite drought-related losses in some states, Brazil is harvesting its largest-ever corn crop.

• As soybean farmer selling has lagged, there is less storage capacity for corn in Mato Grosso

• Synergy between soybeans, corn is alleviating Matto Grosso’s storage problem

The 2022 second corn crop (“safrinha”) was 30.7% harvested in South-Central Brazil as of Jun 30, compared with 12.2% in the same period last year and the five-year average of 23.7%, according to AgRural. Although low temperatures in some states are making it difficult for the grain to lose moisture, which slows down the fieldwork progress a bit, harvesting so far has been the fastest since 2019. That means that nearly 25m tonnes of corn have already entered the market, most of it in Mato Grosso, the country’s largest producer.

Despite some drought-related losses in central and southeastern states, Brazil is harvesting its largest-ever “safrinha” corn crop, with production estimated at 86.5m tonnes by AgRural and 88m by national crop agency Conab. Such high production means it didn’t take too long for photos and videos of corn stacked in the open air in some parts of Mato Grosso to start circulating on social media and news outlets.

Does Brazil Have a Serious Storage Problem?

A discussion of the sharp increase in Brazilian grain production also involves the logistical bottlenecks – often illustrated with images of truck queues, muddy roads and mountains of grain for which there is no room in already crammed silos.

Transportation difficulties have diminished in recent years, thanks to public and private investment in roads and railways, improvements at the ports in the South and Southeast of the country and the construction of new ports in the so-called Northern Arch, which are closer to the producing areas of central Brazil.

Storage capacity has also increased. A survey conducted by Conab shows that static storage capacity grew by 27% between 2010 and 2022, jumping to 177.6m from 139.4m tonnes. The problem is that, over the same period, soybean and corn production combined rose 79%, to 238m tonnes. For soybean and corn production alone, Brazil’s storage deficit is therefore 60m tonnes. If rice and wheat production (more concentrated in the South) is also taken into account, the deficit rises to 79m tonnes.

In the Centre-West region, the soybean and corn storage deficit in the 2021-22 season is around 62m tonnes. The Northeast and the North come next, with 12.7m and 6.8m tonnes, respectively, according to AgRural. The storage capacity is similar to production in the Southeast, whereas the South has a surplus of 21m tonnes – but only because the region had a severe soybean crop failure this year. If it were not for that, there would be a slight deficit, for soybeans and corn alone, although the region is also an important wheat and rice producer, which makes the gap wider.

In Mato Grosso, combined soybean and corn production in the 2021-22 season is estimated by AgRural at 79m tonnes. The state’s static grain storage capacity, in turn, is 39.2m tonnes, according to Conab, which results in a deficit of nearly 40m tonnes. A number like that, of course, stands out. It should be remembered, however, that soybean and corn harvest (in Mato Grosso, virtually all corn is produced in the second crop) takes place at separate times of the year. While soybeans are harvested between January and March, corn is collected between June and August.

The flagship of Brazilian soybean and corn exports, Mato Grosso usually reaches the end of May with 85% of its soybean production already sold and, therefore, with room enough in its silos to receive the “safrinha” corn. This year, however, China’s sluggish imports and expectations of higher prices later in the year have caused farmers to sell their soybeans more slowly. According to AgRural, only 71% of the 2021-22 soybean crop had been sold in the state by May 31. With more soybeans in storage and an earlier and accelerated corn harvest, part of the “safrinha” has been stored in the open – an alternative often used even in the US and nothing that hasn’t happened before in Brazil.

Dynamic Market

As winter is very dry in Mato Grosso, storing corn outdoors for a few days is not a big problem. It’s really is just for a few days because the market in Mato Grosso is very dynamic and things happen fast. Despite being slower-than-normal this year, second corn crop farmer selling reached 59% of the state’s production by the end of May. That means that a substantial portion of the corn that is being harvested already has a final destination and is able to fuel Brazil’s exports, which usually peak in August and September.

One of the ingredients for the success of “safrinha” corn production, in fact, is precisely the way it complements soybeans logistically, along with agronomic and economic synergies. Harvested at the beginning of the year, soybeans are stored in silos and exported mainly in the first half of the year. The “safrinha” corn, which starts to leave the fields in June, enters the storage facilities and then heads to the ports in the second half of the year.

Because of those factors, and even though the photos and videos of mountains of corn in the open attract the attention of those who are unfamiliar with agriculture and logistics in Brazil, one thing is certain: everything is fine with the Brazilian second crop and there is enough corn to supply the world over the next few months.