Insight Focus

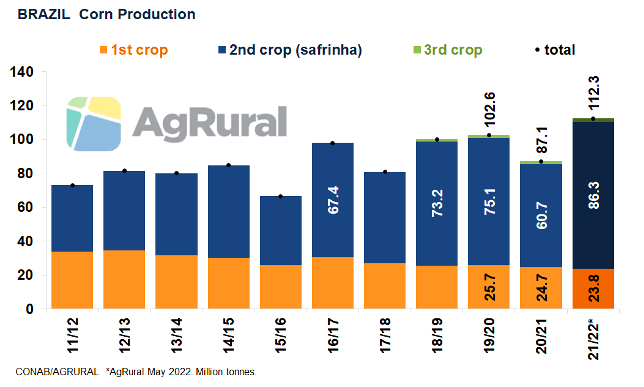

- Record high production on 10% increase in planted area despite drought-related losses

- Brazilian prices hit by forex, harvest size despite bullish Chicago futures, firm export premiums

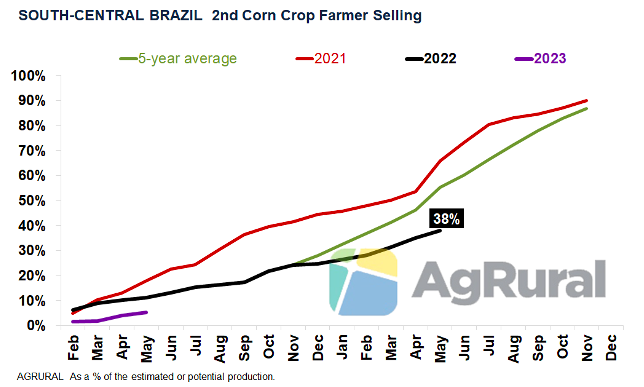

- A weaker Real would help unlock farmer selling, which is at 38% of production

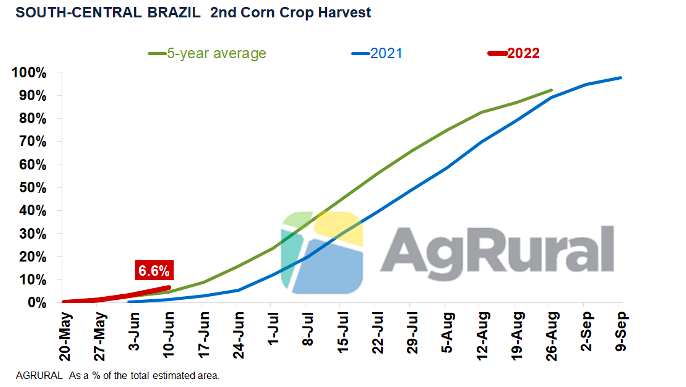

The 2022 second corn crop – the largest safrinha in Brazil’s history and probably one of the most-watched due to the gap left on the international market by the collapse in Ukrainian exports – is being harvested. A weekly survey by AgRural shows that 6.6% of the area planted in Centre-South Brazil had been harvested by June 9, compared with 1.4% a year earlier and the five-year average of 4.4%.

Despite drought reducing the yield potential in some states since April, second corn crop production is forecast by Conab, Brazil’s federal crop agency, at a record 88m tonnes, with a 10% increase in the planted area partially offsetting yield losses caused by the lack of rain.

AgRural is forecasting slightly lower production (86.3m tonnes), but this is still a record high and a huge increase from last year, when planting delays, drought and frost caused a historical crop failure, cutting production to 60.7m tonnes.

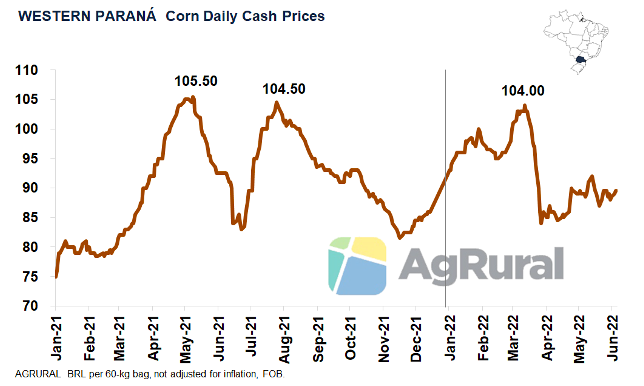

Despite the large crop that is starting to come onto the market, Brazilian farmers have been reluctant to sell corn at the current prices, which are about 15% lower than the historical highs hit a year earlier – a level that was almost reached in March this year.

According to AgRural, only 38% of the estimated production for the 2022 second crop in the Centre-South of Brazil (a region that grows 90% of the country’s “safrinha”) had been sold by producers as of May 31. It is the slowest farmer selling for a second corn crop since 2014.

Waiting for Higher Prices

Although corn prices for delivery from July onwards, when the harvest really picks up, have risen in May, the Brazilian market remained sluggish due to the gap between bids and offers. On the one hand, most farmers are capitalized enough to wait for higher prices over the coming months. Buyers, on the other hand, believe prices will fall sharply as soon as the harvest progresses a little more and the record high production comes onto the market. The recent strength of the Brazilian real has also helped buyers in southern Brazil import corn from Paraguay at competitive prices in response to local producers’ reluctance to sell.

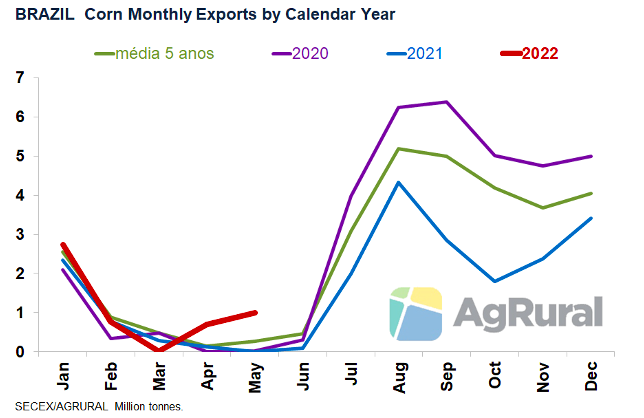

With 38% of the estimated production sold by the end of May, Brazil’s south-central states have around 31m tonnes of corn ready to fuel domestic demand and exports, securing a rapid pace of shipments in June, July and August. However, for exports to pick up and reach the potential 38m to 40m tonnes suggested by the record production, buyers will need to find a way to coax the large amount of corn yet to be sold out of farmers’ hands.

Fear of Further Falls vs. Waiting for New Highs

From now on, Brazilian corn producers basically have two options. The first is to sell at lower prices, for fear that they will fall further in the coming months, pressured by record high production and the possibility that domestic buyers will once again resort to importing greater volumes of corn from Argentina and Paraguay, as happened last year.

The second alternative is to hold on to the newly harvested corn and wait for higher prices that could result from weather problems in the final stretch of the 2022 “safrinha” (frosts until the end of June can still cause considerable damage in areas of Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo); possible weather problems in the 2022/23 US crop; stronger international demand due to lower exports from Ukraine and the slow progress of the harvest in Argentina; and/or a weaker Brazilian real, something highly likely in a presidential election year.

Best Case Scenario

In the first days of June, the Brazilian corn market has been more liquid every time the real fell against the dollar. At the moment, a fall in the Brazilian currency would be ideal to boost farmer selling and exports, as it would result in higher prices in reais, which would satisfy the producer, and, at the same time, reduce the need for importers to raise export premiums to bridge the gap between bids and offers.

Even with futures close to record highs in Chicago, export premiums for shipment in August at the port of Santos are at 90 points, in line with last year, when the second crop suffered a major failure, and significantly up from 65 points in the same period of 2020 and 12 points in 2019, when Brazil exported 42.7m tonnes of corn, a record that still stands.