Insight Focus

- High global food prices are helping India export its stockpiles.

- India is diverting its sugar surplus to make ethanol.

- Might it not be better to encourage farmers to grow less cane and more grain?

India’s farms employ around 250m people and so the government tightly regulates the sector. In recent years farms have overproduced major crops such as wheat, rice and sugar. The government has launched an ethanol programme to soak up some of the excess sugar and grains. But following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, should India slow its ethanol ambitions to help feed the world?

Food vs Fuel: 2020s Edition

The 2020s have been difficult so far. After not quite 30 months we’ve faced a COVID pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and now sharply rising food prices.

Plague, war and rising food prices risk pushing millions of people into hunger. After a decade of increasingly promoting fuels as a way of using surplus food, now is the time to use fuels to make food (mechanised farming, fertiliser, etc.).

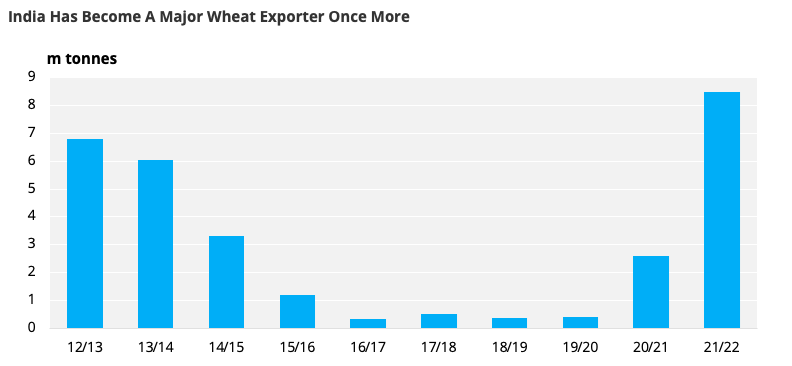

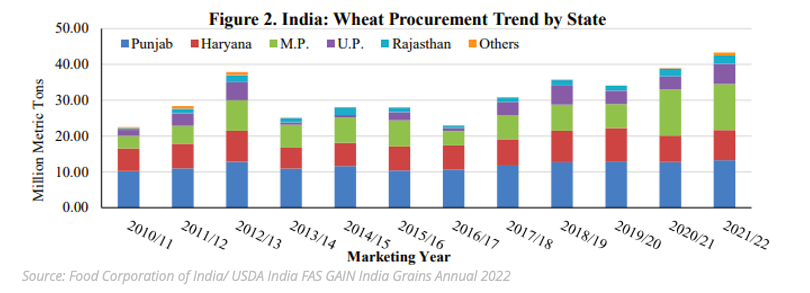

India has large food stocks and suddenly these are necessary. Global wheat prices have risen sharply; Russia and Ukraine are major wheat suppliers. India has become a major wheat exporter overnight, providing food security to countries like Egypt, Bangladesh and Iran.

However, despite its huge production and stockpiles, India’s annual wheat surplus only represents 2% of its total harvest. In other words, a small shortfall in production could eliminate India as a supplier of wheat to the world.

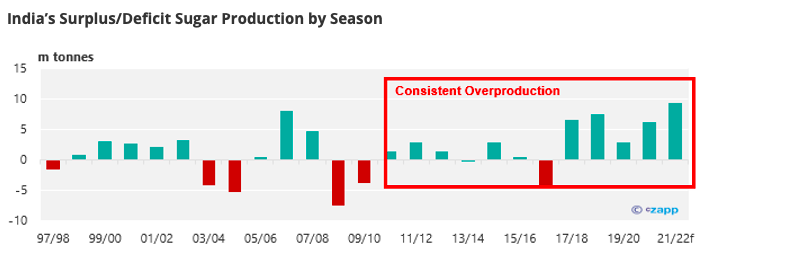

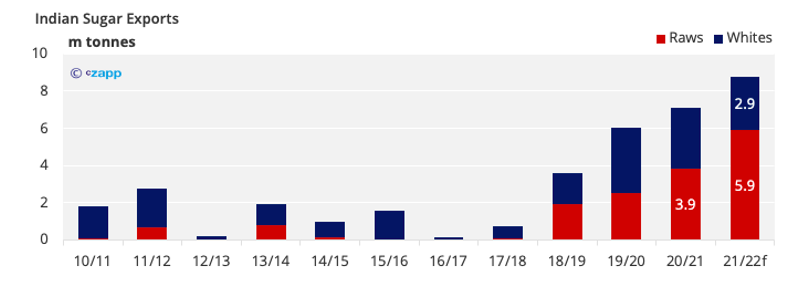

India has also been able to export record volumes of sugar this year without needing any form of export subsidy. As a proportion of production, sugar’s surplus is larger than wheat’s, at more than 25%.

Therefore, despite its recent success India’s copious supplies of food to the world may not last:

- India’s annual wheat surplus isn’t large.

- Sugar and grains are being rapidly being diverted to make fuel.

- India’s current wheat harvest is being threatened by an abnormal heatwave, which has driven air temperatures far above 40 degrees Celsius.

- Indian agriculture is dependent on the monsoon rains. These have been normal for the past 3 seasons but it’s inevitable that they will be deficient at some point.

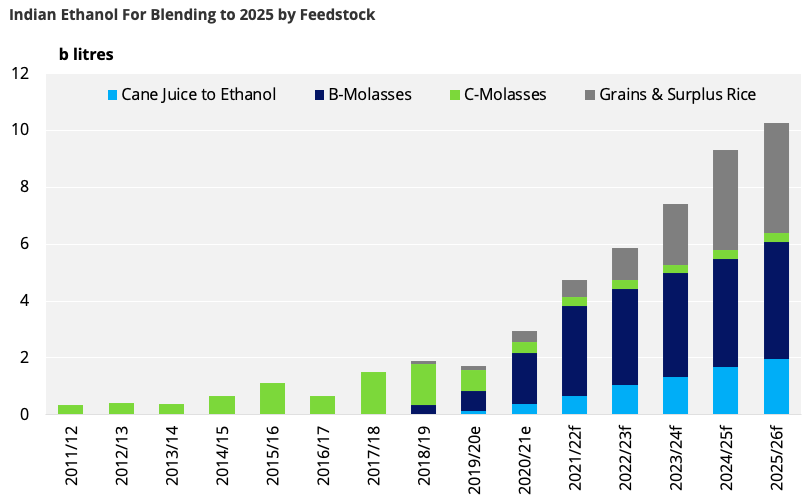

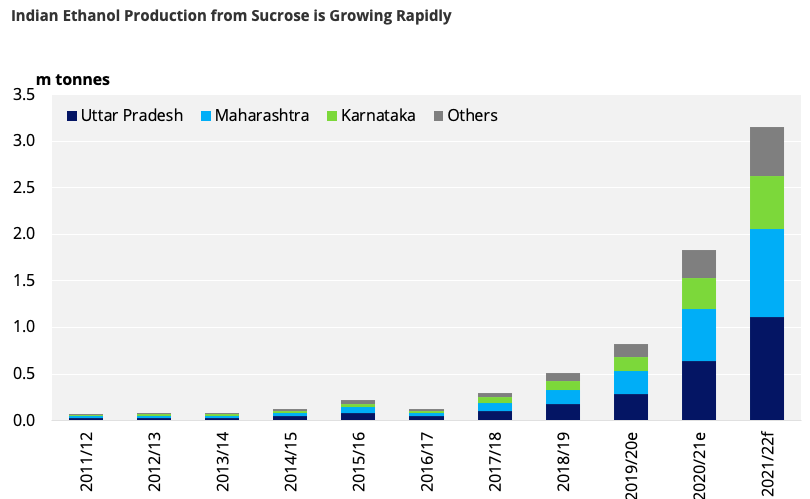

Let’s look in detail at the first point. The government is aiming to reach a 20% blend of ethanol in gasoline by 2025. This was initially conceived as a way of using up surplus sucrose, and the approach made sense in the 2010s when food prices globally were falling. As well as solving sugar overproduction it enhanced energy security and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

We think more than half of 2025’s ethanol requirement will be derived from sugar cane and the remainder from grain-based feedstock. Assuming cane acreage and yields remain constant, this would remove almost all of India’s surplus sugar production.

Back To India’s Food Stockpiles

So India’s sugar surplus is being diverted to fuel and its wheat surplus is being exported. This makes India vulnerable to future crop shortfalls. Where do these surpluses come from and how sustainable are they?

Indian farm policy is also social policy. More than 50% of the 1b population are rural, and human labour remains cheap. The government ensures that appropriate prices are paid for crops so that farmers and farm-workers survive and food is cheaply available. Amendments to the system are therefore sensitive: look at the protests that accompanied the proposed Agriculture Act changes in 2020.

For India, and most of the world, the last 12 years have brought falling food prices. This is good news for the poorest in society, who have access to more affordable food. Indian crop yields have also grown steadily in recent decades, and so at the start of the 2020s India found itself grappling with food oversupply.

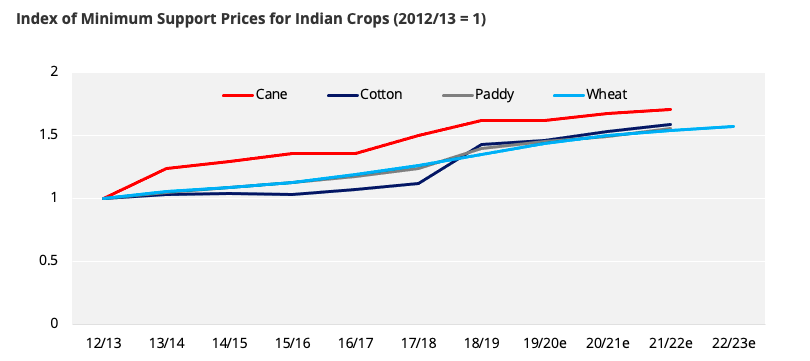

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

However, this excessive food wasn’t cheap relative to other global producers. Minimum support prices for Indian wheat were far above the world wheat price. The Indian government built increasingly large buffer stocks of wheat and rice, and distributed some of these stocks at discounted prices to the poorest in society, especially once COVID hit.

Similarly, Indian sugar costs of production were also far above international prices. To avoid a large stock-build, India subsidized sugar exports to the world market.

While it was incredibly generous of the Indian taxpayer to subsidise sugar prices for consumers around the world, the excess supply pushed global sugar prices lower still, and major producers such as Brazil and Australia challenged India’s policy at the World Trade Organisation. Rather than attempt to overhaul cane pricing, India’s government arrived at another solution: ethanol.

What Can India Do?

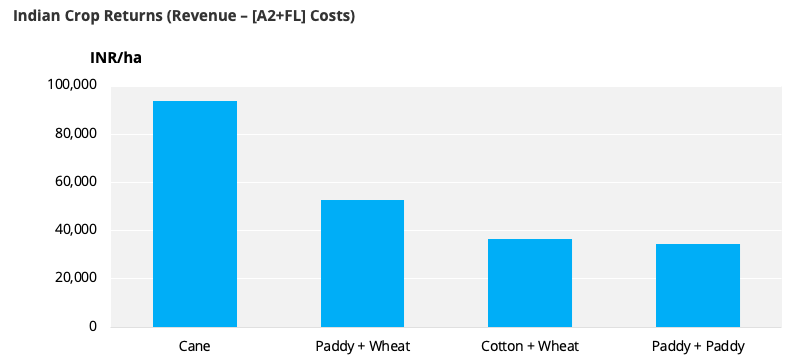

We’ve already shown that sugar’s surplus is much larger than wheat’s (25% vs 2% of production). Given vast surpluses in sugar and more borderline surpluses in grains, the government could explore ways to persuade farmers gradually in marginal cane growing areas of Uttar Pradesh to switch back to wheat, and in similar areas of the South West to move towards soy or paddy. This would help boost Indian and global food security, especially in the event of adverse weather.

Sugarcane returns dwarf those of all other crops. Sugarcane returns have been set so high that it is sometimes grown on marginally suitable land.

Food security will be a major issue in the coming years, and India’s politicians have an opportunity to act proactively. High global crop prices could ensure India’s farm sector stands on its own two feet without needing government handouts like export subsidies or stockpiling.

Given the sensitivity of farm policy, this would be a difficult process to get right. But India could gradually slow cane price rises over the coming seasons. Cotton prices have recently been held at lower levels and this has successfully led to farmers planting other crops. If grains support prices were to rise more rapidly farmers would start to reallocate their marginal land away from sugar and back into grains.

India could also signal to farmers that food is more important than fuel by moving its E20 target from 2025 back to 2030. This would enable more work to be done on alternative feedstocks to be used for ethanol generation rather than sucrose or grains.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities