Insight Focus

- Brazil’s record wheat production in 2021/22 has spurred exports instead of reduced imports.

- Mercosur tax rules and government intervention prevent farmers from increasing the planted area.

- A new project by Embrapa aims to expand wheat plantings in tropical areas by 40% by 2025.

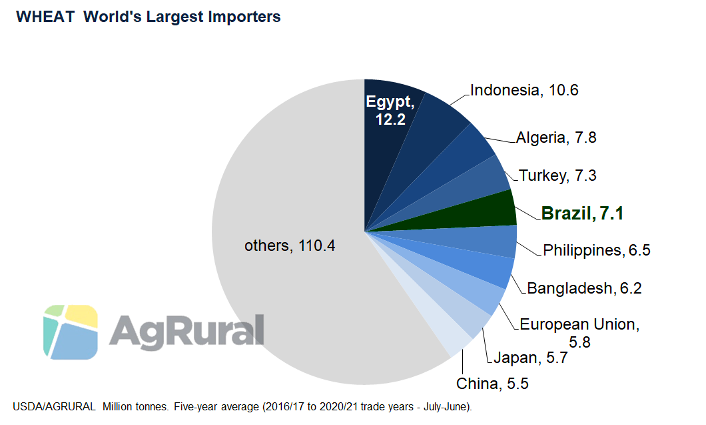

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the end of February and new momentum to the war in the Black Sea region has lifted agricultural prices and reignited, not only the debate in Brazil over its great dependence on fertiliser imports, but also criticism about its role as a major wheat importer. More used to being listed among the largest agricultural exporters, Brazil does not repeat this feat in the wheat market, being the world’s fifth-largest importer, behind Egypt, Indonesia, Algeria and Turkey.

Brazil doesn’t normally import wheat from Russia and Ukraine because freight rates between the Black Sea region and South America result in prohibitive CNF prices, and also because the wheat exported by both countries pays a 10% import tariff to enter Brazil.

But the war in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia, combined with weather woes in China and in the US, have made wheat prices soar to historically high levels around the world, including in Argentina (Brazil’s main wheat supplier). And paying more for this basic food staple has made Brazilians revive an old debate over whether the country should try to become self-sufficient in wheat.

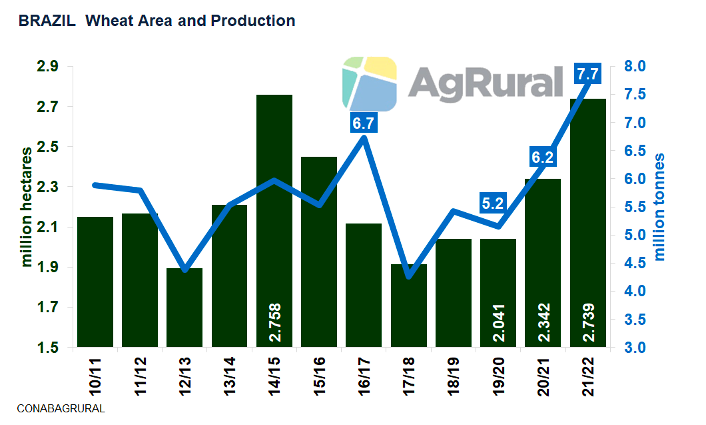

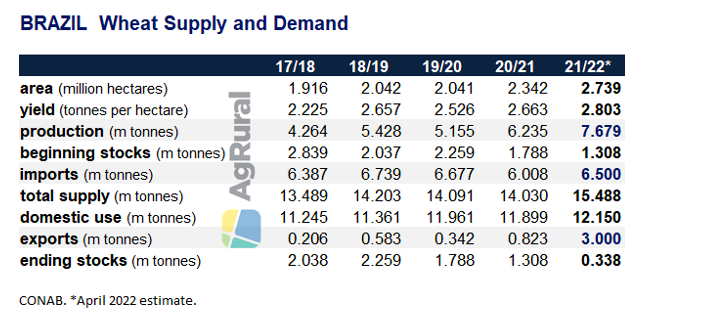

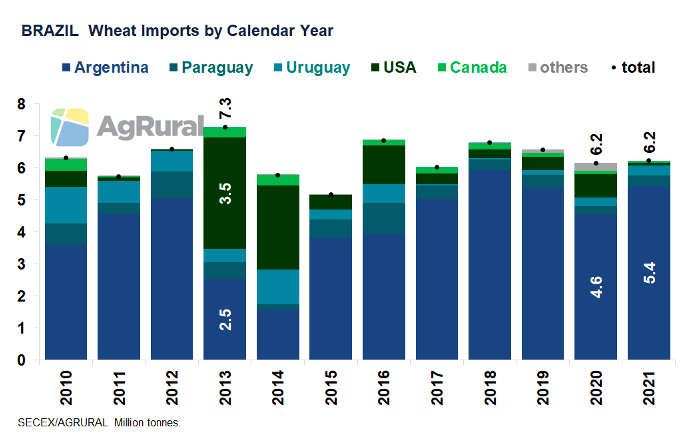

Even before the war in Ukraine, the bullish sentiment in the wheat market since 2020 has made Brazil boost its planted area, reversing a decline that took place between 2015 and 2019. In the 2021/22 crop, sown in May and June last year and harvested between October and December, Brazil produced 7.7m tonnes of wheat, a record high, thanks to a 17% increase in the planted area and the best yields in five years. Even so, the country is expected to import 6.5m tonnes in 2021/22, which ends on July 31, because part of the larger production is being exported.

Exports on Fire

Brazil’s federal crop agency Conab projects 2021/22 wheat exports at 3m tonnes, compared to 823k tonnes in 2020/21. In Q1’22 alone, Brazil exported 2.2m tonnes, nearly four times more than in the same period last year. The main importers were Saudi Arabia (505k tonnes), Indonesia (360k), Morocco (288k), South Africa (236k) and Vietnam (229k). Apart from Saudi Arabia and Vietnam, the other countries barely appeared on the list of Brazilian wheat destinations in Q1’21.

But why is Brazil exporting wheat instead of using it to plug the gap in its own domestic market? And what are the odds of the country increasing its production in the coming years, eventually becoming self-sufficient?

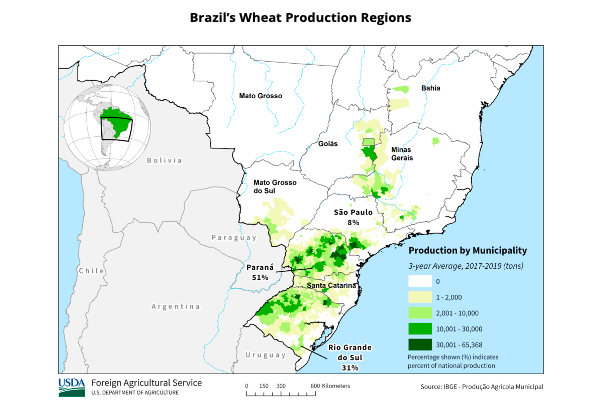

Even when its crop fails, Brazil exports small amounts of wheat. The Brazilian product shipped abroad is normally used by importers as animal feed due to its low quality – normally a result of excessive rainfall during harvest, which is carried out in the spring, a period of the year when precipitation volumes increase in southern Brazil, where 90% of the wheat produced in the country is grown.

But even the good wheat harvested in Brazil is not good enough to meet the country’s demand, as its gluten content, for example, is lower than that found in the product imported from Argentina. Therefore, reducing Brazil’s dependence on imported wheat implies not only an increase in production, but also investments in better quality.

Tropical Wheat

Other states than those located in southern Brazil, especially São Paulo, Minas Gerais and Goiás, have been producing wheat for some years, but the warmer climate, the need for irrigation and greater competitiveness of other crops, such as corn, prevent farmers from expanding the planted area.

Since 2020, the Brazilian government has been preparing a project called Decentralised Execution Term for Tropical Wheat, which aims to develop new technologies to boost production in São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Goiás and the Federal District, Mato Grosso do South, Mato Grosso and Bahia.

A praiseworthy initiative, the project is a result of the domestic wheat industry lobby and is endorsed by Embrapa, the state-run agricultural research agency which shares the credit, among many other achievements, for turning Brazil into a soybean-producing and exporting powerhouse. The plan is to increase the wheat area in those non-traditional states by 40% until 2025. In absolute numbers, however, that represents an expansion of just 100k hectares, too little in face of a domestic consumption that exceeds 12m tonnes.

The Enemy Lives Next Door

In Brazil’s southern states, where weather conditions are more favourable than in other parts of the country, wheat faces fierce competition from more profitable crops, such as the “safrinha” corn in Paraná. Another problem is the high climate risk posed by frosts during reproductive stages and by rain at harvest. But the worst enemy lives next door and is called Argentina.

A traditional wheat producer since the 19th century, Argentina has the climate and the soils of which Brazil can only dream. Argentina produced 21m tonnes of wheat in 2021/22 crop is likely to export 15m tonnes. In 2021, 87% of the 6.2m tonnes of wheat imported by Brazil came from Argentina. The rest was purchased from neighbouring Paraguay and Uruguay (5% each), and from the US and Canada.

In addition to the short distance from Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay have an advantage that secures their big share in the Brazilian market. As Mercosur members, those countries do not pay the 10% Common External Tariff to sell their wheat to Brazil. And there is more: the wheat imported from neighbouring countries does not pay a state tax paid every time a Brazilian mill buys domestic wheat from a state other than that in which the mill is located.

With larger production, higher quality and tax advantages that translate into more competitive prices, Argentine wheat is an obvious choice for Brazilian mills. That kind of competition prevents Brazilian farmers from expanding the planted area, except in years with a significant price spike, as was the case in 2021 and as is also happening now in 2022.

Government Interventions

But Brazilian producers’ lack of enthusiasm for wheat tends to dominate even in years of tight supply and higher local prices. Due to the great impact that wheat products have on inflation, the Brazilian government usually intervenes in the market, suspending the 10% tariff that applies to imports from outside Mercosur. The measure is normally taken when the wheat crop fails in Brazil and/or in Argentina and explains why the US and Canada sometimes have a significant share of the Brazilian wheat market.

With that kind of competitor and tax disadvantages, it’s difficult for Brazilian farmers to become big fans of wheat. Therefore, despite Brazil’s success in adapting foreign agricultural crops to its climate and soil conditions, it’s highly likely that the country will remain on the list of the world’s largest wheat importers for a long time to come.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Africa Eyes Cassava to Plug Wheat Deficit