Insight Focus

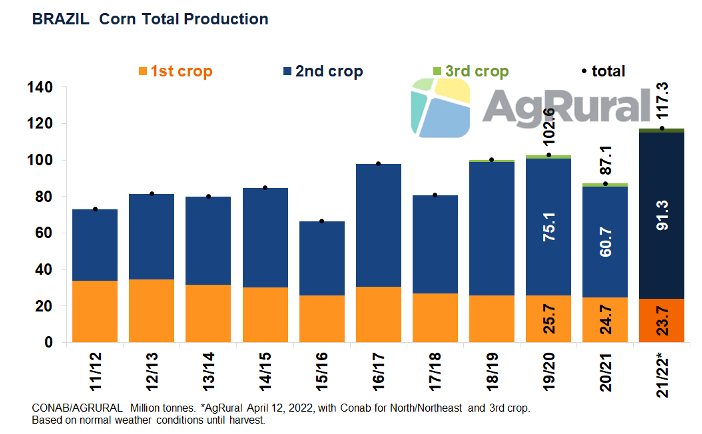

- Brazil’s safrinha corn crop could jump 50% year on year on optimal weather and timely plantings.

- All eyes on weather, with lack of rain already an issue.

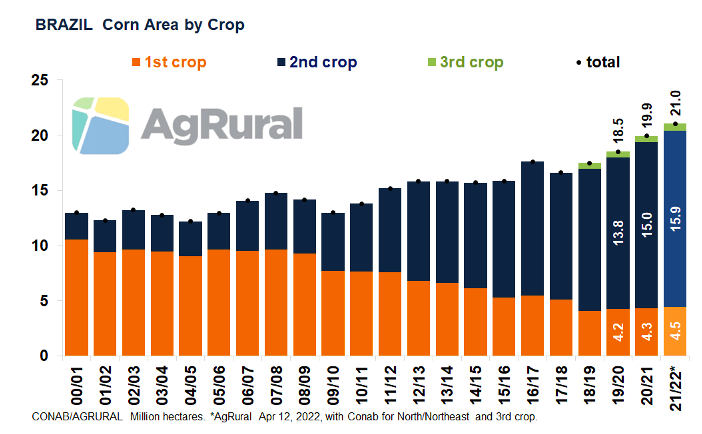

- Safrinha crop accounts for 75% of Brazil’s corn production and the bulk of its exports.

After last season’s historical failure caused by planting delays, drought and frost, the 2021/22 safrinha could climb 30m tonnes (+50%) on the year thanks to a 7% increase in planted area and an expected rebound in yields.

For this to materialise, though, the second crop needs favourable weather conditions over the next 60 days.

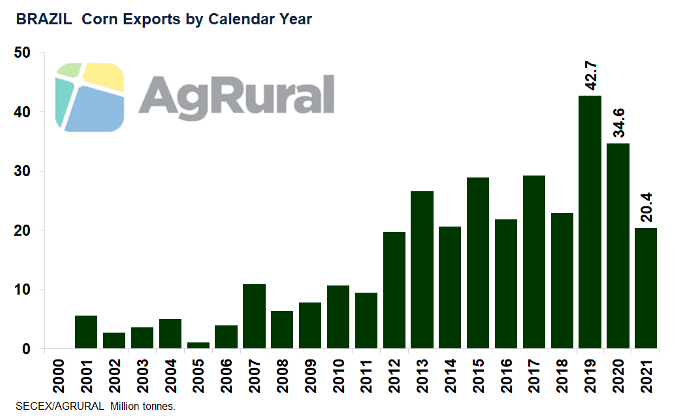

A large crop is not only key for the Brazilian consumption but also for its exports, especially when the other three major global exporters are struggling – the US has cut its planted area by 1.6m hectares, Argentina’s crop is smaller due to drought and Ukraine is in the midst of a war.

The second corn crop is planted from early January to mid-March, right after the soybean harvest. It’s called “safrinha” (Portuguese for “little crop”), not because it’s smaller than the first, but because producers view it as complementary to the soybean crop in terms of planted area and farm revenue.

A Risky Crop by Definition

The second corn crop pollinates and fills grains in April, May and June, when it’s autumn and early winter in Brazil. During that period, a steep decrease in precipitation occurs in most of the country, and that makes safrinha a risky crop. Below average rainfall will hit yields.

Although the 2022 safrinha has been developing well so far, a drier pattern seen in the second half of April is already a concern for farmers in areas of Centre-South Brazil, especially in a few regions of Mato Grosso, Goiás and Minas Gerais that had already received lower volumes in the first half of the month.

Brazil does not have extreme low temperatures in the autumn-winter, but the fact the second corn crop develops in that period of the year, and not in the spring-summer (as is usual for corn) also takes its toll on yields.

Even when the crop is not hit by frosts (which are relatively common in Paraná, southern Mato Grosso do Sul and southern São Paulo), the smaller differences between daily temperatures, along with overcast conditions, naturally limit yields. Planting within the ideal window is therefore the first step towards having a successful safrinha.

Good Start and High Hopes

This year’s safrinha was planted within the ideal window and weather conditions in the second half of March and early April were favourable, encouraging several crop forecasters to increase their production estimates. In its monthly crop report released earlier this month, Brazil’s federal crop agency, Conab, raised its projection for total production (first, second and third crops combined) from 112.3m tonnes to 115.6m tonnes (with the second crop alone jumping from 86.2m tonnes to 88.5m). The USDA, which releases numbers for total production only, increased its forecast by 2m tonnes, to 116m tonnes.

AgRural has also raised its estimate and now puts total production at 117.3m tonnes, with the second crop accounting for 91.3m tonnes of that total. If this holds true, the second corn crop will be more than 30m tonnes larger on the year, when a nasty combination of planting delays, drought and frost reduced production from an initial potential of 81m tonnes to only 60.7m tonnes.

Safrinha Key for Brazilian Corn Exports

The safrinha comes with another advantage: it’s harvested between June and August. Brazilian exports peak in September, when the US (the largest exporter) has little left to ship.

This is why the second crop is key for Brazilian exports. In 2021, when the crop failed, Brazil shipped just 20.4m tonnes of corn compared to 34.6m in 2020 and a record-high of 42.7m tonnes in 2019. Now, in 2022, if there are no significant weather problems over the next 60 days, exports should approach 40m tonnes.

Such an increase in Brazilian exports will be welcomed by importers, with Ukrainian exports down and production looking poorer for 2022/23. With the crop being planted during the war.

Sluggish Farmer Selling

A challenge for corn buyers around the world, however, has been getting Brazilian farmers to sell. A survey conducted by AgRural shows that just 31% of the estimated 2022 safrinha production had been forward sold by the 31st March, down 19% on the year and 10% from the five-year average.

Haunted by weather woes and in hopes for higher prices down the road, Brazilian producers are not exactly keen to sell their corn right now.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Brazilian Ethanol Production to Triple by 2030, Upping Corn Prices

Brazil’s Meal and Oil Exports Hit Record Highs Despite Smaller Soy Crop

Explainers That May Be of Interest…