Insight Focus

- A food crisis is looming in Africa because of the disruption to Black Sea wheat exports.

- African countries are trying to mitigate this by boosting domestic food production.

- Cassava is a potential solution to African food insecurity.

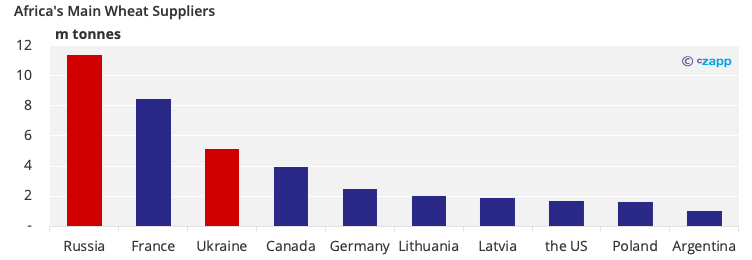

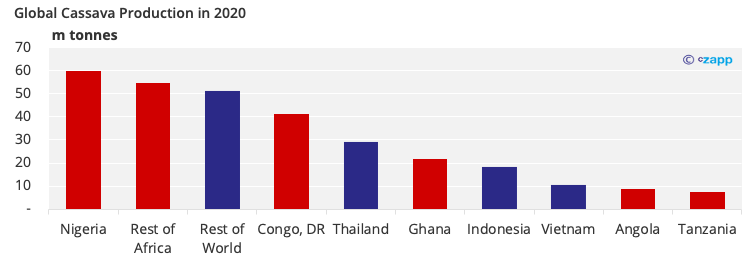

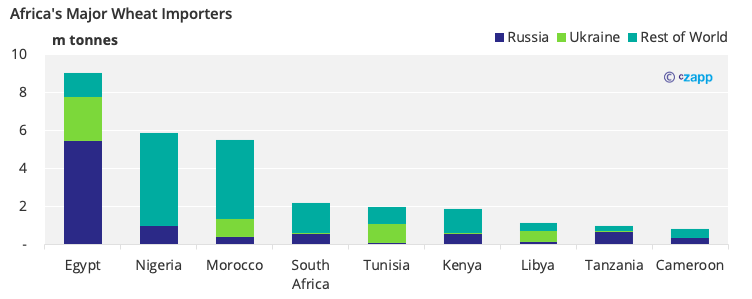

One of the consequences of the war in Ukraine is a looming food crisis in Africa. North Africa and the Sahel region rely heavily on food imports. The Nigerian government recently announced a mandate to partially replace wheat flour with cassava starch. Nigeria, the largest cassava producer in the world at over 60m tonnes a year, imports 1m tonnes of wheat from Ukraine and Russia every year.

Africa’s Breadbasket is on the Brink of Collapse

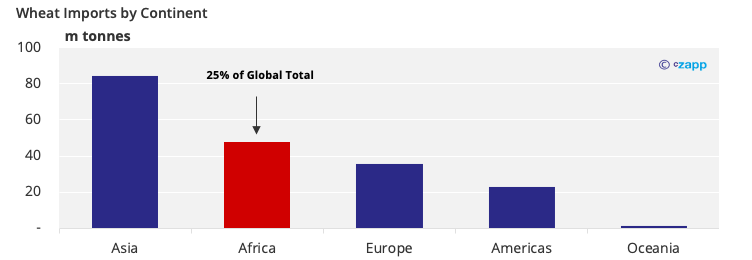

Africa is far from self-sufficient in food. Every year, a quarter of wheat in the international market goes to Africa, according to data from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Russia and Ukraine play a crucial part in Africa’s food supply, accounting for nearly 40% African wheat supply in 2020.

The war in Ukraine is therefore jeopardising the food security of most African countries. We’ve discussed the wheat self-sufficiency campaign in Egypt in the north, the food crisis in Sudan in the east, and the vicious circle of food crises and political instability in most African countries.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, countries such as Nigeria and Tanzania are trying to boost domestic food supply to mitigate the looming crisis. These countries have better agricultural conditions than barren and crowded North and East African countries.

Can Cassava Ensure African Food Security?

Cassava is extensively cultivated as an annual crop in tropical and subtropical regions for its edible, starchy, tuberous root. In Ghana, it’s used as a rotation crop with corn on the savanna to preserve soil fertility, but farmers generally favour it as it copes better with poor soil conditions than wheat and rice.

Originating from South America, cassava has found a new home in Africa. In 2020, according to FAO data, African countries accounted for 64% of the world’s 300m tonne cassava output.

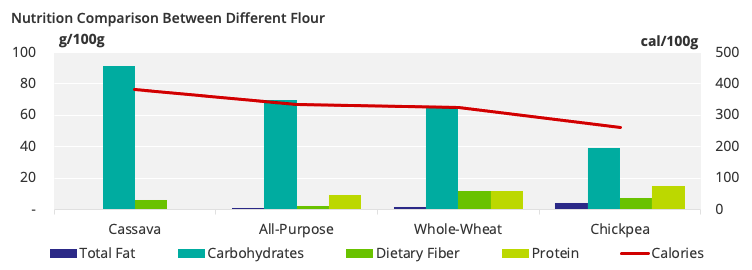

In Africa, cassava is usually boiled for direct consumption in farmers’ households. It could, however, be used more commercially if it were processed into cassava flour or tapioca to blend with other flour. It could also be made directly into bread. Cassava flour is gluten-free and rich in energy but contains fewer minerals and less protein than wholewheat and chickpea flour.

As war in Ukraine has proven the fragility of foreign food supply, African countries must face the food crisis with what they have on hand.

Nigeria Mandates a 10% Cassava Flour Blend

The Nigerian government has mandated a 10% inclusion rate of cassava flour in bread and encourages a 50% inclusion rate in other baked goods.

Research institutes such as the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Ibadan say that, if 75% of all Nigerian bakeries stick to the mandate, the country’s annual wheat imports would drop by 25% (1.48m tonnes).

The 10% blend ratio was first announced in 2011 as part of the Cassava Flour Inclusion Initiative,but the idea was rejected by the Nigerian Congress in 2014. In November 2021, though, President Muhammadu Buhari vowed to end wheat imports by 2023, and reviving this initiative is one way of achieving this goal.

Will This Be Another Short-Lived Attempt?

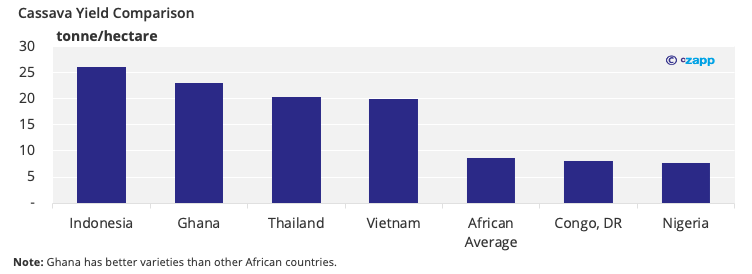

Although Africa produces most of the world’s cassava, yields in many African countries are low as farmers have limited access to new varieties.

Farmers also lack the technology to effectively process cassava into flour. Nigeria is a good example of this.

Since the war in Ukraine broke out in late February, African countries have accelerated their adoption of new varieties. Zambia and Nigeria have made breakthroughs in developing cassava varieties that are more adaptive and resistant to diseases, according to Nigerian state media. They’ve also started to invest more in storage infrastructure and are subsidising farmers to adopt new varieties.

Another issue, though, is the threat from those that wish to use native and modified cassava starch and chips as feedstocks in the ethanol production process. Producing ethanol with cassava is more lucrative than selling it as food. Cassava supply for industrial use is limited, however, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, especially in major consuming countries like Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ghana.

The key factor in how the African cassava industry develops will be the duration of the war in Ukraine. This will determine when Black Sea grain exports return to normal. If the war ends soon, there’s still time for grain prices to return to pre-conflict levels. Pre-war import levels would discourage African countries from investing more in the development of cassava varieties and agricultural infrastructure to achieve food self-sufficiency. But, if the war drags on, this would be the cue for African countries bolster their food security, and cassava would likely have a role to play in this.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Ukraine Crisis Adds Another Twist to Sudan’s Food Insecurity Spiral

Egypt to Boost Wheat Production with Black Sea Disruption

Explainers That May Be of Interest…