- Last time, we spoke about what happens when sampling goes wrong.

- Sampling is important as, if it’s carried out incorrectly, crops can become worthless.

- Today, we focus on the interaction between the seller (farmer) and the buyer (the grain merchant).

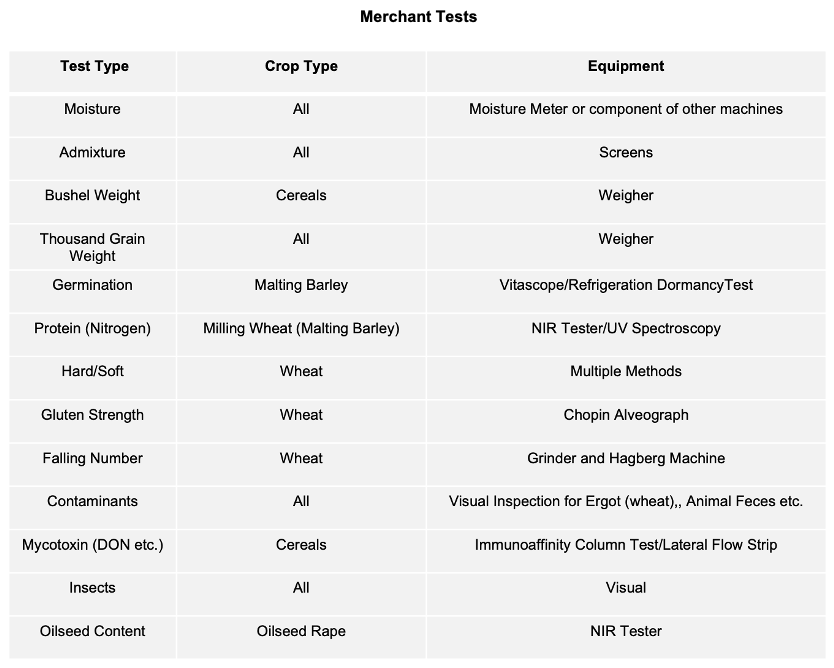

Merchant Samples

As we explained previously, the farmer will likely have some basic testing equipment, such as bushel weighing and moisture testing machines. However, these only assist with cleaning and drying produce. It’s only when that’s complete that a representative sample can be drawn, either by the farmer, or the merchant’s representative from storage.

The merchant will have a laboratory and that’s where more sophisticated tests can also be carried out. There are literally hundreds of tests, but human consumption grades have many more available (and used) tests compared to animal feed grades.

Wheat (biscuits, pasta, etc.) and peas (marrowfat, maple, etc.) are particularly complex. The more specialist the need, the more likely a ‘buy-back’ contract will be in place to meet the buyer’s needs.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

A lot. Although some produce is sold for immediate movement at harvest (spot), a large portion is sold for different (forward) months.

For example:

- 500 tonnes of feed wheat for March/April, 180 GBP/mt ex farm, buyers call (the merchant decides during the two-month period when the grain is collected).

- 300 tonnes of oilseed rape for February to April, 450 GBP/mt delivered (D/D), EMQ (Equal Monthly Quantities); the farmer will have a lorry, deliver in trailers, or arrange the haulage.

The time lag between sampling after harvest and moving the grain in both these cases is significant.

In theory, the grain should be re-sampled just before movement. It often isn’t, and for a large variety of reasons.

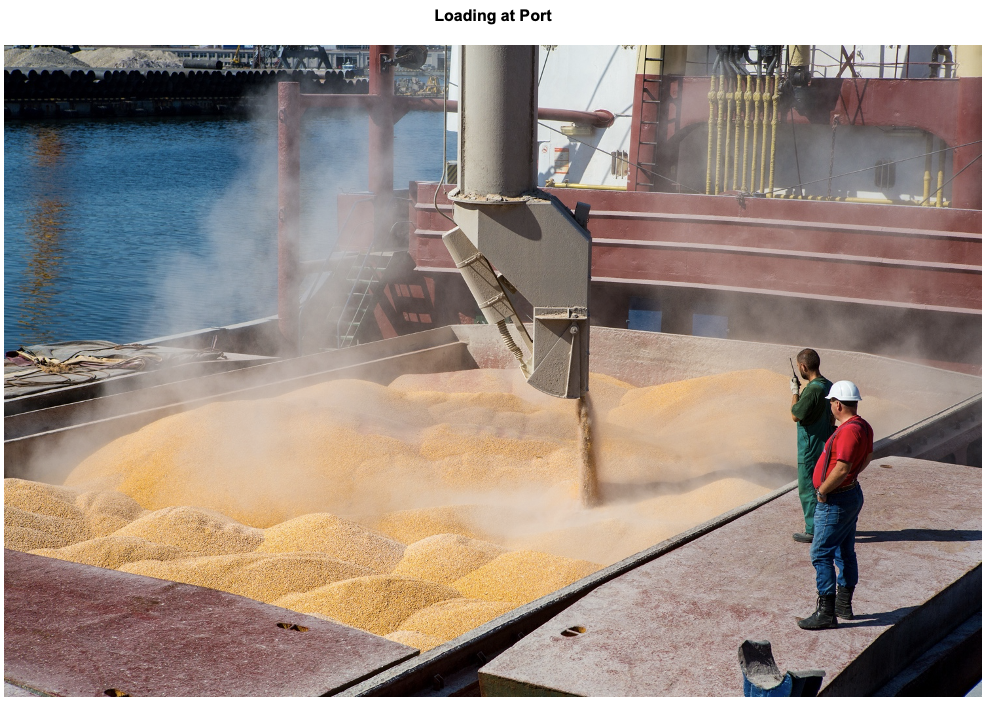

Quite often, a large vessel will arrive at a port and must be loaded quickly so the shipper doesn’t pay overtime penalties (demurrage), and there’s insufficient time to re-draw samples from the farm.

The grain during the time lag could have acquired a range of problems such as heating up (from excessive moisture) to insect infestation. These types of problems can lead to deductions (claims) or, in some cases, out and out rejection.

A significant portion of the grain can be sold forward, even before it’s harvested, especially when the farmer likes the forward price. On occasion, the farmer on testing doesn’t have sufficient quality (or quantity) to meet the contract specification. This can allow the merchant to buy replacement material if they choose and charge the farmer the price difference (if any). Premium grades sold forward should always have contractual allowances back to the feed price, as that’s otherwise like a dangerous bet on the weather and other events.

Most grain is moved by a haulier. One good procedure is for the farmer to draw samples on the vehicle before it leaves the farm, place it in a bag, and close it with a tamper proof lead seal before finally having the driver sign for it. This is then called a ‘reference sample’ in case of any dispute, where it can be sent to a third party for testing. This simple procedure is surprisingly rare; it’s much more common to use the buyer’s compulsory (in many countries) similar reference sample. If the testing of the buyer’s reference sample is upheld, the costs of testing are charged to the seller.

Each new season, equipment must be calibrated for that harvest by sending samples for testing between buyers and merchants or other qualified third parties. It’s notoriously difficult to get a good ‘read’ on the first delivered grain of the year.

Grain sampling is hot, physically demanding, and dusty work, especially around harvest.

In my first few weeks as a trainee merchant, I was sent to sample a massive on-floor heap of grain of many thousands of tonnes. To carry out correct sampling with a grain spear would have taken a whole day. So, I resorted to what’s called ‘scooping from the top’, i.e., not using the grain spear to sample at different depths. This is hugely important, especially as grain moisture on an in-floor drying system is highest on top (the grain is dried from underneath the heap). When the grain was delivered, there were many claims and I’m still embarrassed to this day!

Another problem relates to bin storage, where it can be almost impossible to draw an accurate sample. This will either be the case due to limited access to portions of the grain or because it’s too dangerous to tread on the grain in an open top bin.

Rejections

It may come as a surprise, but some rejections or claims on loads are part of risk management. Two examples will suffice:

- A large vessel of medium protein (9.5-10%) premium soft wheat is being loaded at a port. The seller believes the buyer’s average protein for the vessel is running towards the high end. They deliver wheat they know is only testing at 9.2% but there’s a chance it will be taken anyway. If rejected, the wheat will go to a local feed outlet. This can be done either at the risk of the merchant alone or as a dual risk with the seller.

- A mill is taking milling wheat (typically above 11% protein and below 15% moisture with allowances). As mills often have limited silo storage, they need a constant stream of wheat, sometimes every day. If the seller’s wheat is out of specification (with allowances), the buyer may decide to offer extra penalties, especially if the problem can be blended away with other wheat, rather than outright reject it.

Conclusion

Know the testing and contractual procedures, as both a buyer and a seller!

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- Inspection and Certification: The Basics

- Inspection and Certification: When Sampling Goes Wrong

- Sustainable Agriculture: Arable Farming

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…