- So far, we’ve focused on issues related to global warming and arable farming.

- Special attention has been placed on the use of synthetic fertilizers and sub-optimal cultivation techniques.

- Here, we focus on a concept known as ‘Integrated Pest Management’.

What Are Pests?

For the purpose of definition, pests are insects, fungal diseases, and a mixed group including nematodes (wireworm), molluscs, bacteria, birds, and rodents. Weeds are often included in this description when discussing Integrated Pest Management (IPM).

How to Manage Pests Sustainably

Unlike with fertilizer, we can’t just reduce the amount of pesticides used per hectare, nor can we use the same pesticide more frequently or even use a similar type of pesticide.

We can, however, use beneficial species, crop rotation, genetic diversity, improved timing, new technologies, along with a broad range of other tools.

Pesticide Resistance

When you’re sick and the doctor prescribes you antibiotics, they’ll insist you finish the course of treatment, even if you feel better. That’s because the ailment being treated can develop antibiotic resistance and become less effective both to you and others.

Plants can also develop resistance to, for example, pesticides and in the case of herbicides, the damage isn’t immediately obvious.

Twenty years ago, I worked with expert Dr. Ian Heap on this subject. Using field collected weed samples, they were potted in the laboratory and different rates of herbicide were applied. If the weed had developed resistance, nothing was going to kill it, even if we applied ten times the recommended rate.

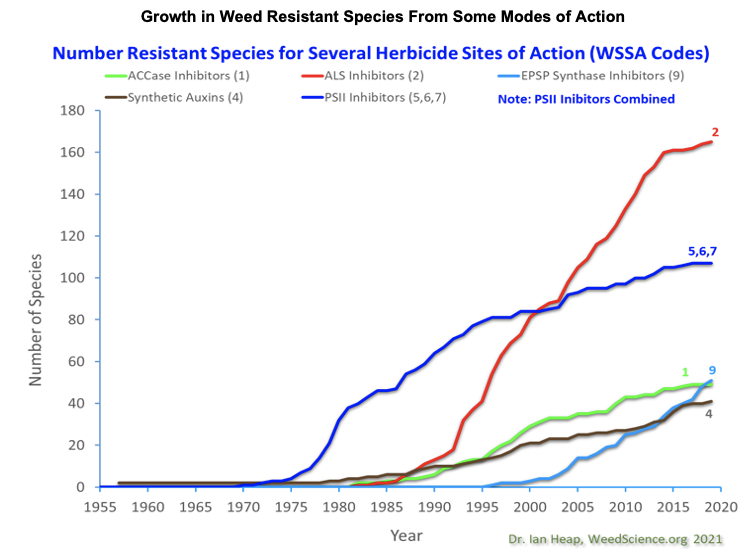

With herbicides, there are deemed to be 11 Modes of Action (MOA), which are targeted at different sites within the plant.

The below graphs shows that with the application of more herbicides, especially from the 1980s, the number of resistant species of weeds has grown rapidly and several species have resistance to multiple MOA groups.

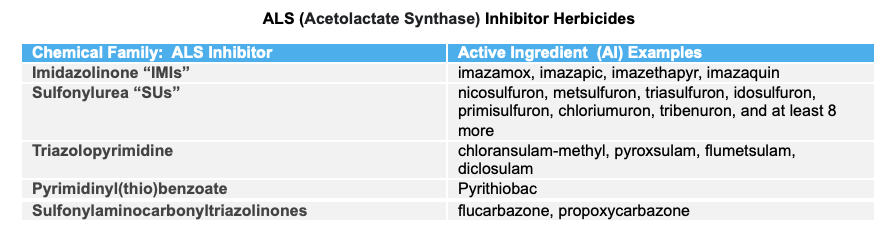

An even more disturbing picture has also developed: if a weed is resistant to a herbicide from one of the MOA groups, it’ll be resistant to every member of that chemical family. The below table shows an example for ALS (Acetolactate Synthase) Inhibitors.

That’s a huge armoury of products eliminated if a weed shows resistance to any one of the AI’s.

A similar situation exists with insecticides and a good example is the Colorado Potato Beetle where resistance to 57 insecticides and several MOA’s are recorded.

This is a serious pest and is found in Europe, but not normally in the UK. UK agronomists know that, if they find, they must notify the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA). A real outbreak, as it is often confused with ladybirds, would likely lead to quarantine of a large area. It is gluttonous: one adult larva is capable of consuming 10 cm2 of foliage per day and untreated 100% loss is possible. It’s not too picky either as it likes tomatoes and aubergines as well.

Current Solutions

If the scenario painted sounds alarming, it needn’t. Human ingenuity and related science is almost boundless. But, for sure, there are rules to be followed which are important to SIA.

In the case of resistant weeds, we’ll be exploring a range of appropriate strategies. It’s possible to kill weeds mechanically and without using fertilizer. In the UK, there’s currently a brand new system in commercial trials in wheat with three sequential robots called prosaically Tom, Dick and Harry.

The weeds are ‘zapped’ by electric currents (more on this technology in a future article). In the case of the Colorado Potato Beetle, a range of ‘friendly’ destructive bacteria look promising and there’s been some success with pitfall traps. These are plastic lined trenches, which catch the beetles as they move towards the potato fields in the spring as they are unable to fly at this point.

We also have to be realistic. In one case, there’s an urgent need for an increase of pesticides (and many other methods), when we later discuss the case of noxious and invasive species.

Modelling Integrated Pest Management

Global pesticide production totals around 3.5m tonnes per year, with the largest proportion from herbicides. Although this production generates greenhouse gases, IPM is more concerned, not with overall volume of Active Ingredients (AI) applied per hectare, but with the environmental impact of them as some are more damaging than others.

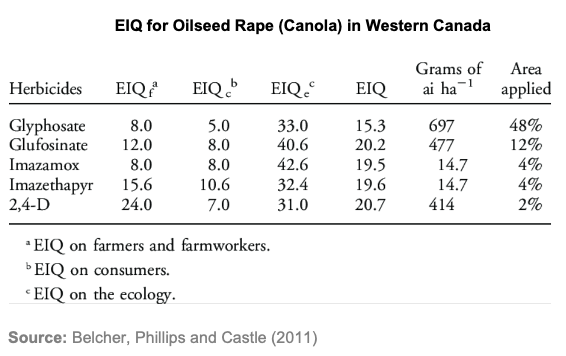

Other components to be considered are the impact on the worker/applicator and the consumer. This was the basis of the Environment Impact Quotient (EIQ) developed by Kovach (1992). Real data, such as toxicology of the AI, are combined with qualitative proxy estimates to produce a weighted index. The output is one number per pesticide product, the EIQ, which shows the optimum choice and allows direct comparisons to be made.

In the below example, Glyphosate was considered the best choice from a range of common herbicides.

EIQ is still used today, although it’s come under serious criticism by mathematicians.

I think it’s a useful first step in identifying key issues, and a much more ambitious model, still under development is the EU Footprint Project and its related Product Environment Footprint (PEF) studies. This is a massive piece of work, however, and not just used for agriculture. The protocols and calculations run to hundreds of pages. It attempts to calculate the environmental footprints of the Earth’s nine planetary boundaries, the safe limits for the Earth’s systems most critical processes. It remains to be seen how useful this will be at a farm level given its complexity.

IPM has its own set of rules and science and knowing this is vital to the decision making process.

Other Opinions You May Be Interested In…

- Sustainable Agriculture: Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO)

- Sustainable Agriculture (UK): Not So Sweet Soils