- India’s government wants a 20% blend of ethanol in gasoline by 2025.

- Most of this ethanol will be made from sucrose derived from sugar cane.

- India will therefore export less sugar to the world market in the coming years.

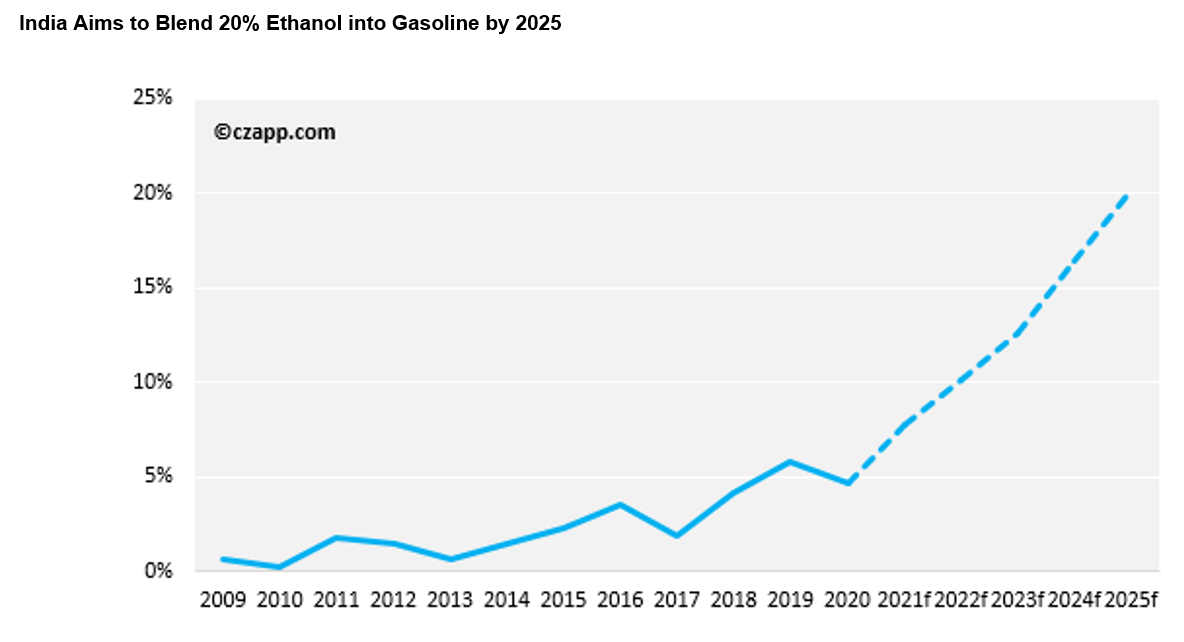

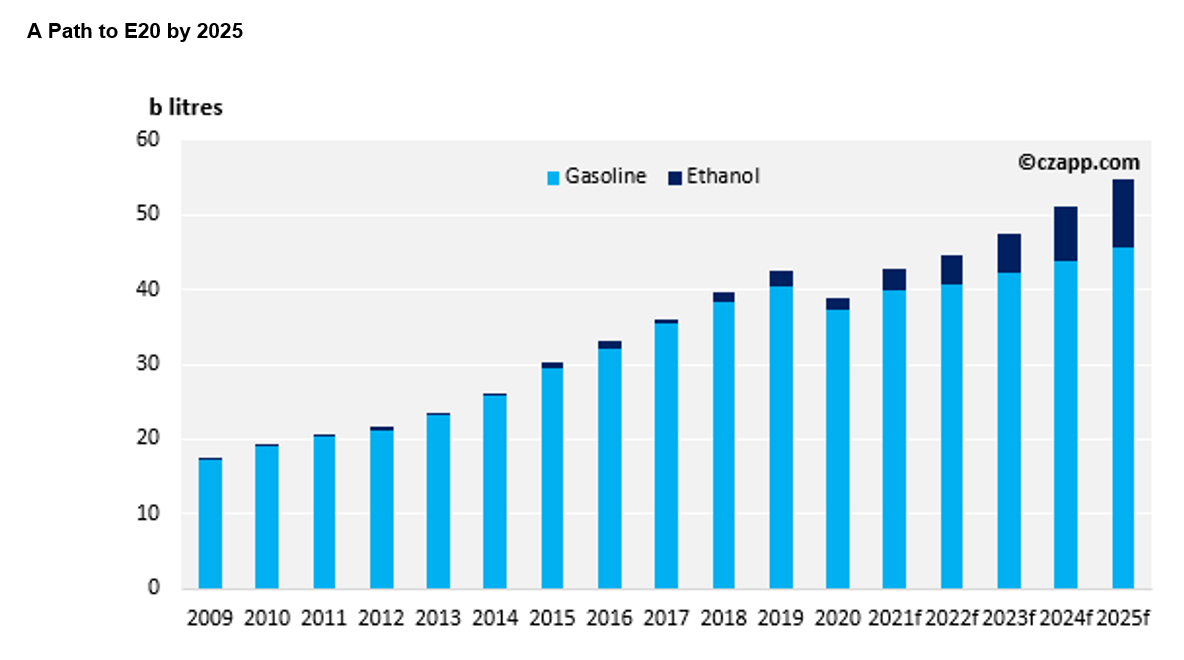

The Indian government aims to blend 20% ethanol into gasoline from 2025 and (confusingly) has also directed oil companies to sell E20 from 2023. It intends to use India’s huge surplus of sucrose to make this ethanol, meaning less sugar will be available for export.

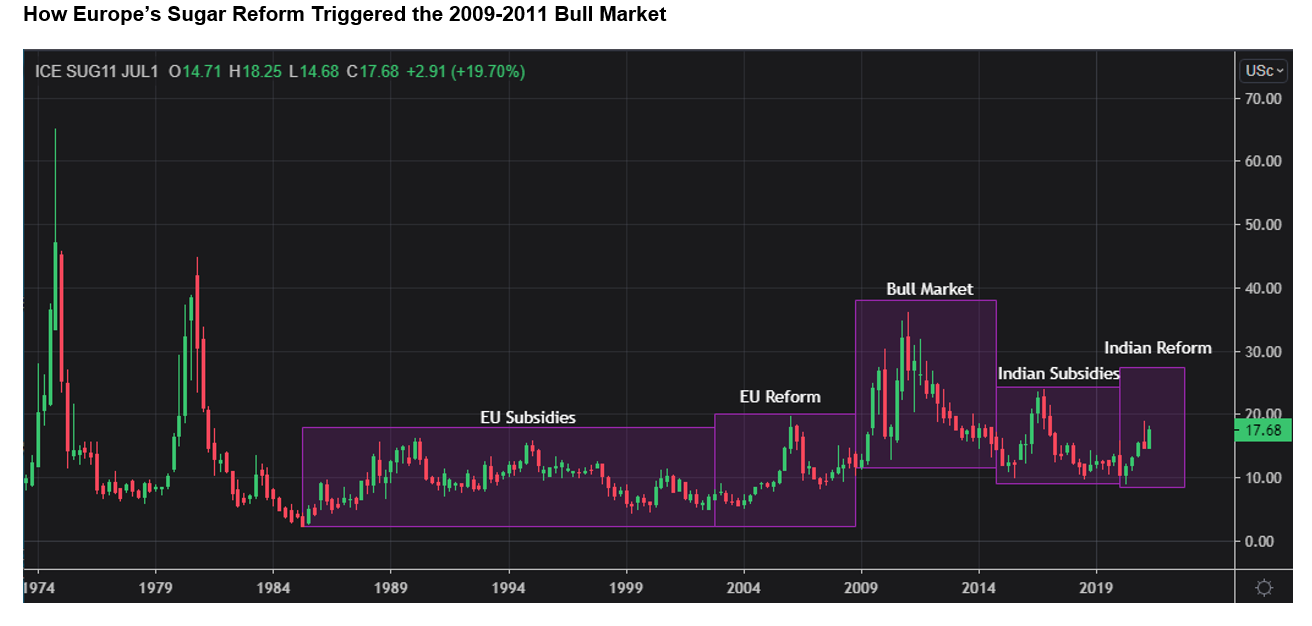

India’s subsidized sugar exports have smothered the sugar market for the last 10 years, repeatedly driving raw sugar prices down to 10c/lb. India’s ethanol programme is therefore the largest change in the sugar market since 2002-2008, when the European Union (EU) reformed its own subsidized beet sector.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

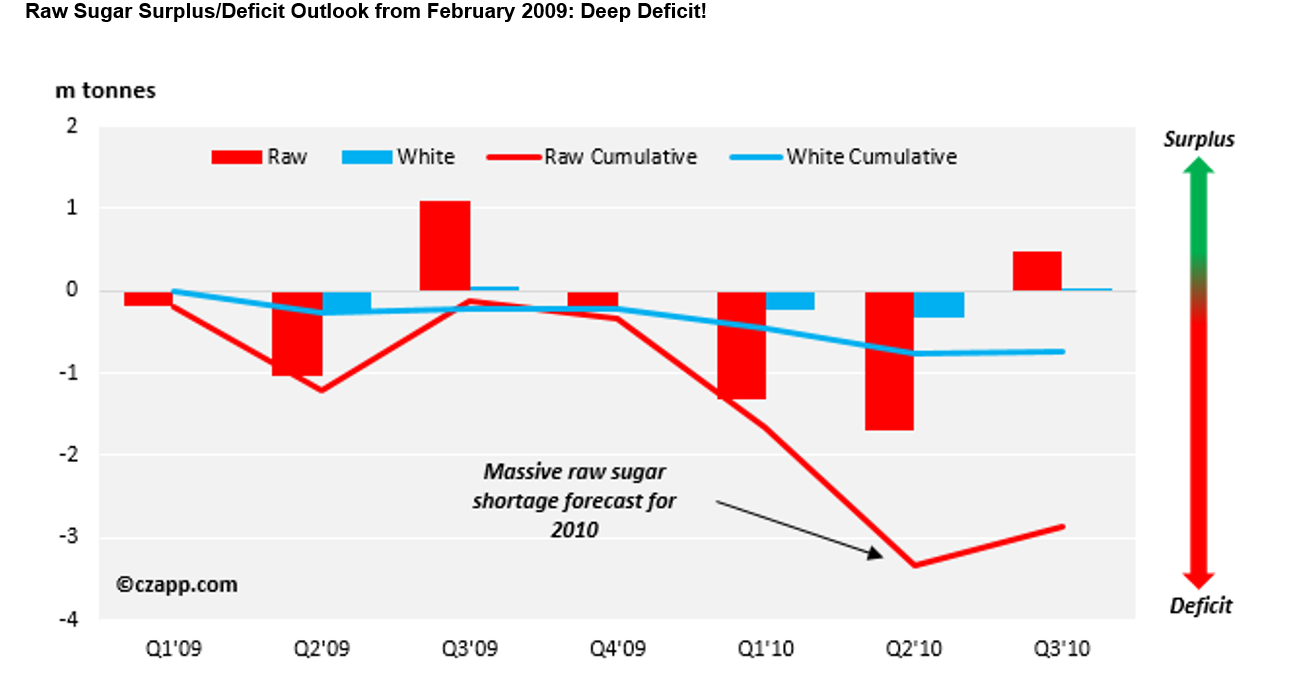

European reform led to the sugar bull market of 2009-11, when raw sugar prices traded to 30-year highs above 36c/lb. India’s reform could have a similar effect.

European Reform and the Last Bull Market

There are clear parallels between European reform in the 2000s and India’s cane sector reform today.

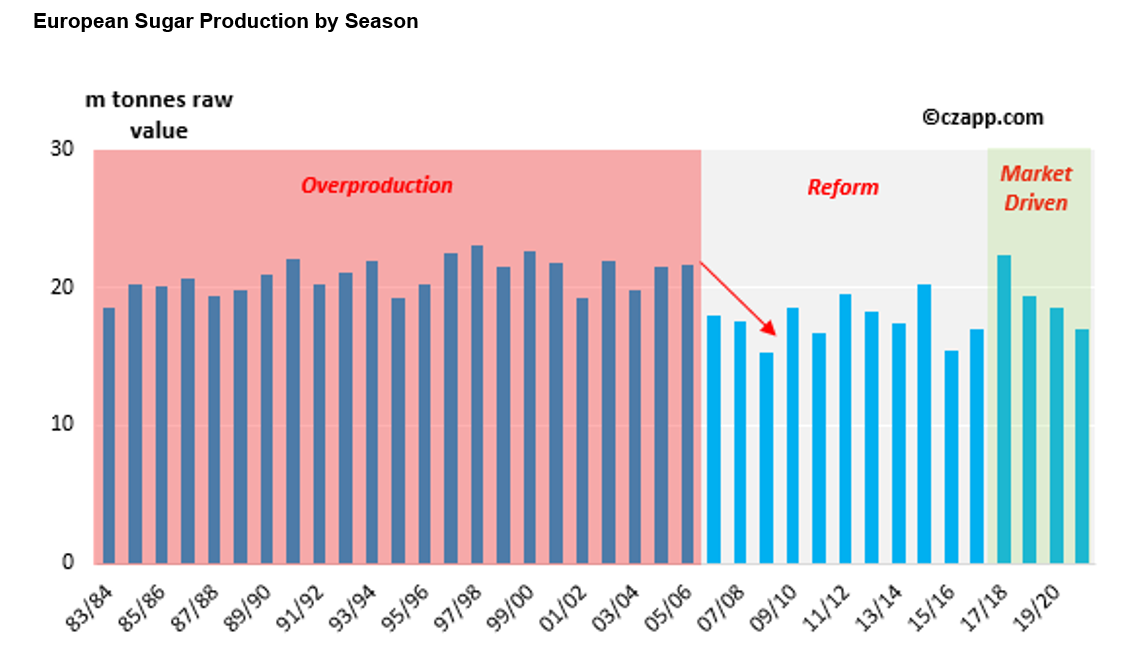

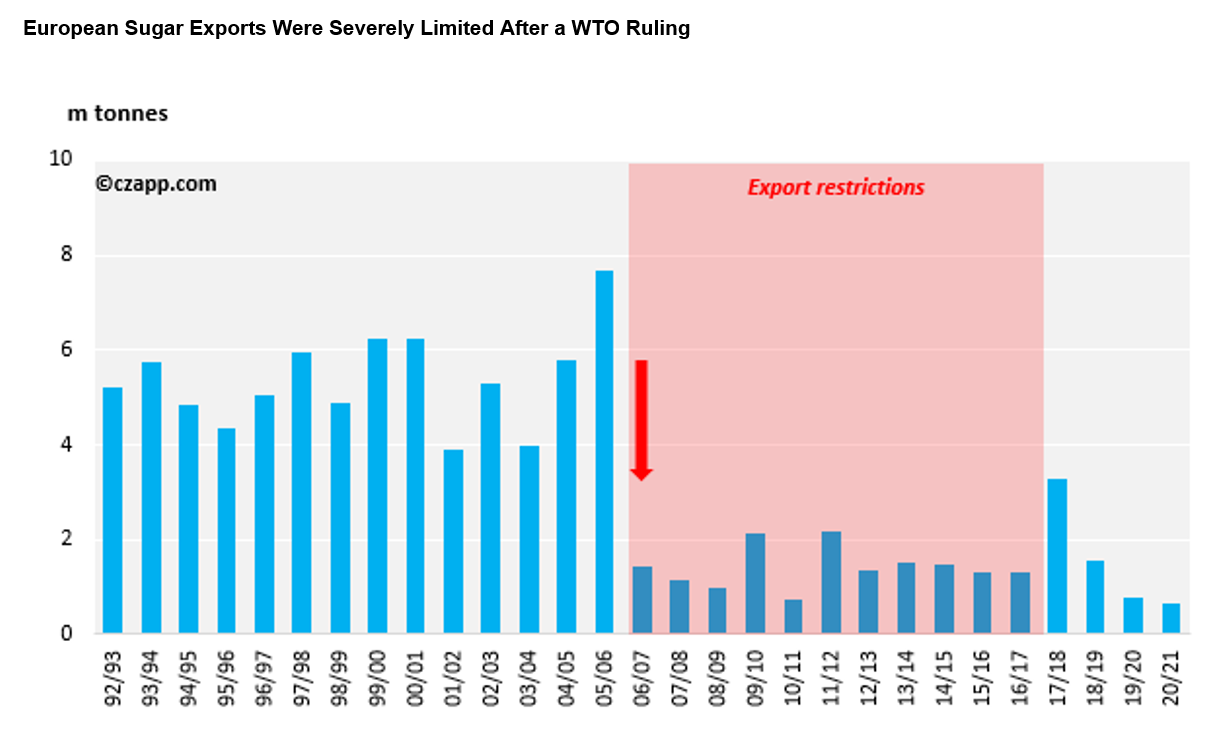

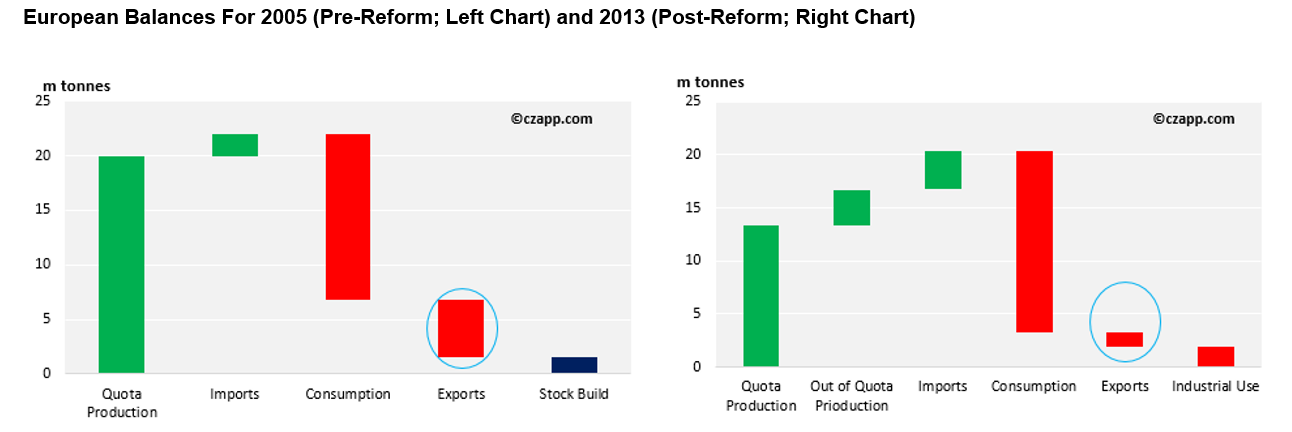

From the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s the European Union dominated the world’s sugar market. Europe set production quotas for beet sugar following the price volatility of the 1970s, to ensure sugar was affordable. But in time the European sugar regime led to overproduction of sugar and the excess was exported to the world market.

Europe was challenged at the World Trade Organization (WTO) by Australia, Brazil and Thailand, who claimed that the exports were subsidized and depressing sugar export returns. The WTO ruled against the EU at the end of 2002, finding that above-quota ‘C’ sugar exports were effectively cross-subsidized. Total European sugar exports each year were limited to 1.374m tonnes by the WTO ruling.

As a result, the European Commission paid Europe’s least-efficient producers to stop growing sugar beet. The Commission then imposed a bloc-wide production quota of 13.5m tonnes from October 2008 onwards, putting the continent into a deficit which would be met by imports.

Within a few years the EU moved from being a bureaucracy-directed sugar exporter to a market-based sugar importer. Beet producers became attuned to production costs and reluctant to sell at a loss. As a result, global sugar supply became more driven by price and stock levels became more driven by commercial considerations, not politics.

No-one understood the full implications in late-2008. The world’s financial system was close to collapse following Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy and European sugar reform was only being discussed by sugar nerds. But removing the EU’s guaranteed cheap sugar supply meant the market was much more vulnerable to shocks.

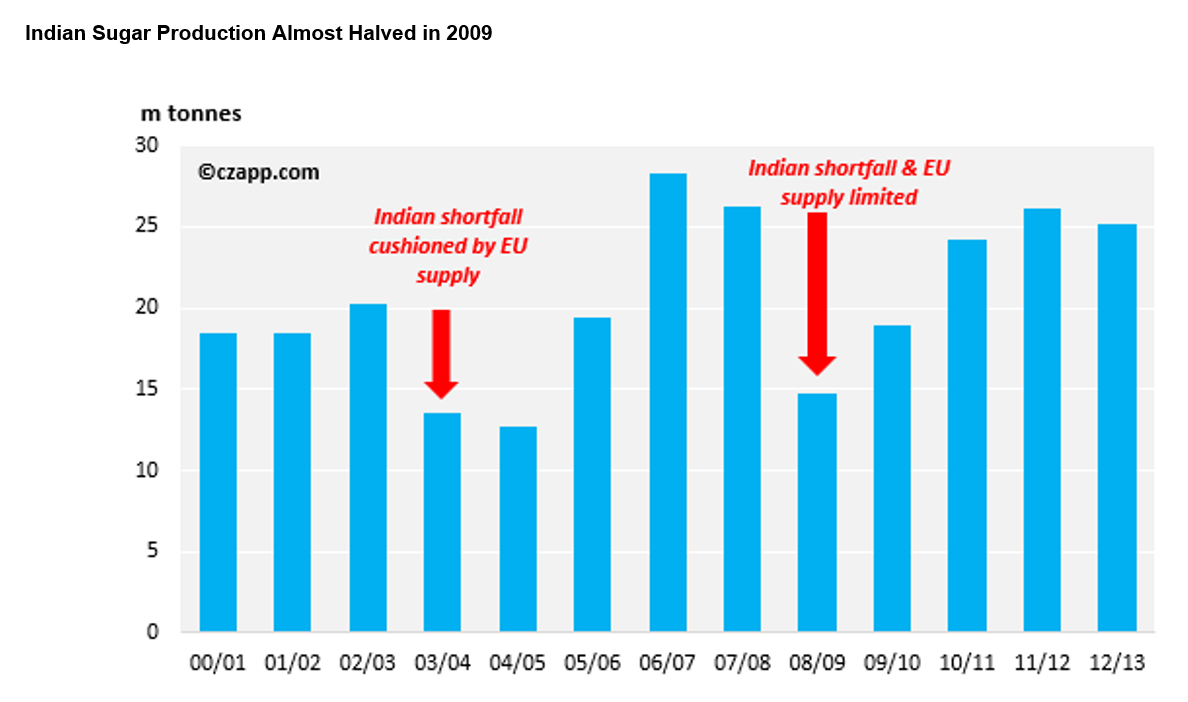

The shock came from India. In 2009, Indian sugar production fell to 14.7m tonnes, almost halving in a year. India swung from exporting sugar to the world market to needing imports, quickly.

But cane takes 12-18 months to mature after planting and so the world’s major cane sugar producers were unable to respond. Beet is an annual crop and so Europe had previously been able to respond quickly to changes in world market price. But by 2009 European producers were limited by production quotas. Faced with a shortfall in sugar supply, prices rallied, first to 30c and then to 30-year-highs of 36c.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

Indian Reform and the Next Bull Market

The sequence following European reform was:

- Subsidized sugar supply depresses prices.

- No incentive for price-sensitive suppliers to increase production.

- Subsidized supply is removed.

- Market shock which cannot be resolved, driving prices higher.

- This sequence applies to India today.

India is now the only major country in the world offering direct export support. In fact, India’s entire cane economy is controlled by the government which:

- Sets the cane price mills must pay farmers,

- Dictates when mills start crushing and the volume of sugar they must sell each month,

- Sets the minimum sugar sales price,

- Subsidizes sugar exports.

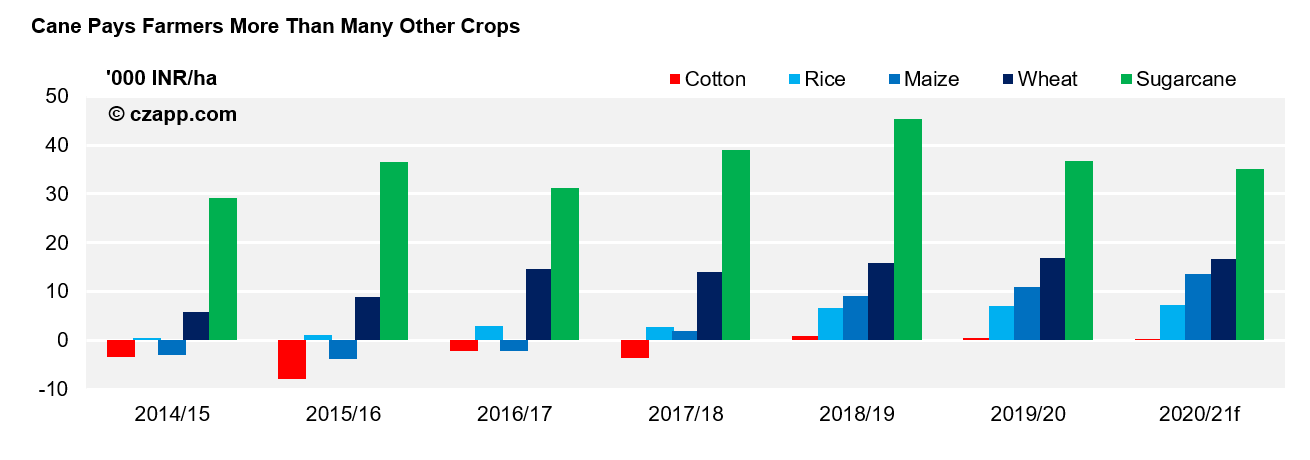

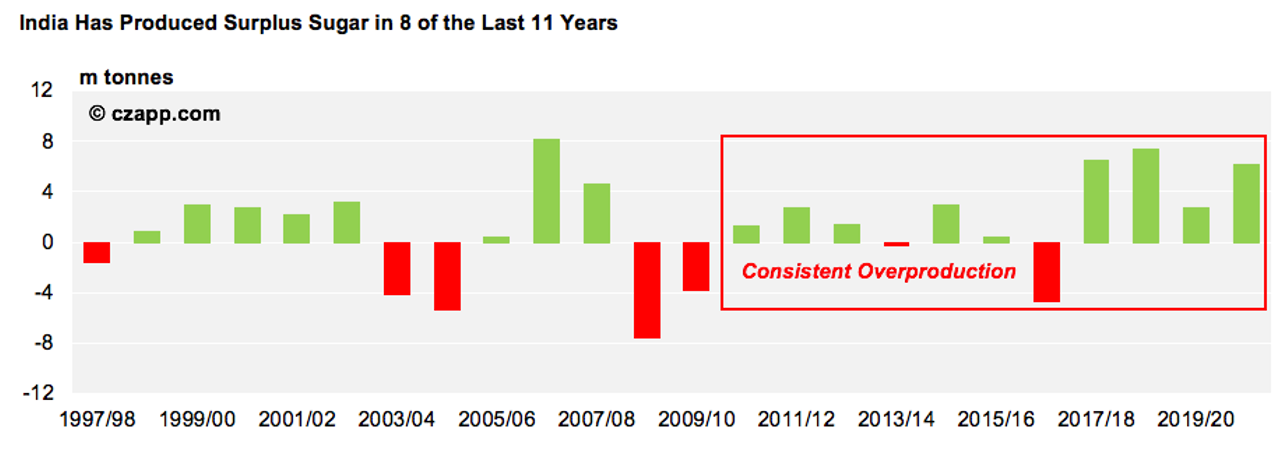

Cane returns are so strong that for many farmers it’s the preferred crop, resulting in overproduction of sugar. High cane prices mean that this sugar is expensive to make and cannot be profitably exported. The only way to stop domestic sugar stocks from building has been to subsidize exports.

India has subsidized sugar exports since 2014, blanketing the world with cheap sugar and pushing prices towards 10c/lb. India’s entire cane economy has therefore been challenged at the WTO by Australia, Brazil and Guatemala. A first ruling on the case is due within weeks.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

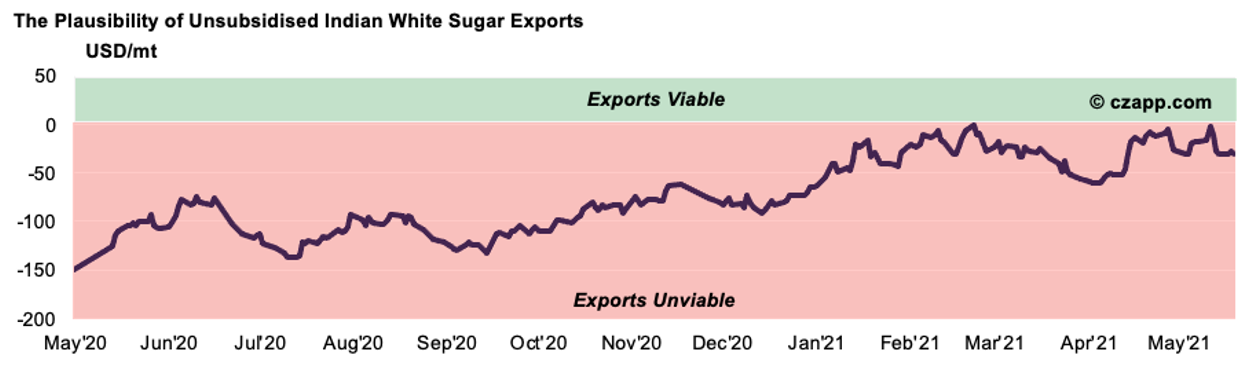

Regardless of what the WTO rules, the Indian government seems to want to stop the subsidy. It’s admitted they are not allowed under WTO rules after 2023. It announced the subsidy for 2021 later than in previous years after conducting a review of whether they were necessary. It also recently cut the subsidy on offer for the final few tonnes sold in 2021. It’s possible that the government doesn’t subsidize sugar exports at all from 2021/22, instead allowing the world market to rally to a level at which unsubsidized exports become viable.

However, the government also wants to preserve rural incomes and so cannot reduce the high cane price. India will continue to produce excess sugar in the future. The government has decided the best way to solve the problem is to develop a local cane ethanol industry, like that in Brazil.

Rather than pay millers to export sugar, they are paying millers to build distilleries capable of processing cane juice or high-sucrose molasses into ethanol for blending with gasoline. In 2018, the government announced it was aiming to blend 20% ethanol into gasoline by 2030. This target was then moved to 2025 last year and accompanied by incentives to the cane industry to rapidly expand their distillation capacity, notably INR 165b low-interest loans.

Reaching E20 by 2025 is a stretch target; in 2020 India’s ethanol blend was only around 5%. It’s going to be hard to quadruple this rate in 5 years. But sometimes stretch targets are inspirational and lead to astonishing performance.

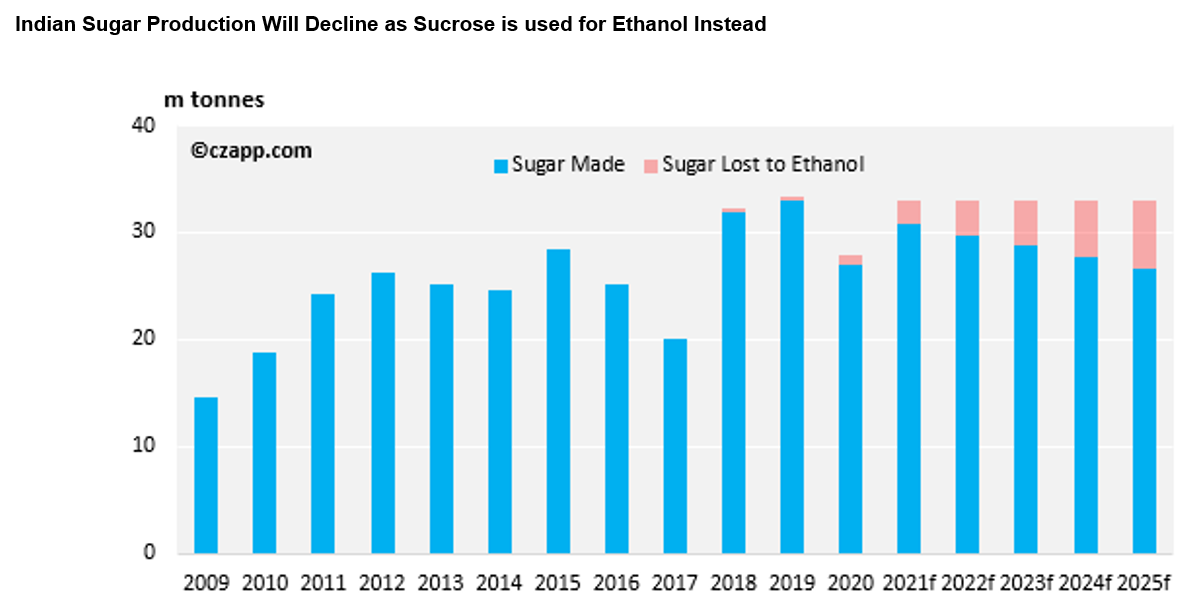

If the industry is successful, around 6b litres of ethanol could be made from cane juice and molasses in 2025, reducing local sugar production by more than 6m tonnes. By 2025 India will swing from making at most 33m tonnes of sugar a year to 27m tonnes. With consumption today at around 25m tonnes and likely to grow in the future, India will no longer be a major surplus sugar producer and exporter.

As India’s gasoline demand rises, so will the demand for ethanol. By 2030, it’s possible India could need almost 13b litres of ethanol to meet an E20 blend, diverting more than 10m tonnes of sugar production. In this situation, either India will need regular sugar imports, or Indian cane acreage will have to increase, or cane yields will have to improve. Cane can take up to 18 months to mature after it is planted. New more productive cane varieties take several years to be proven and gain acceptance. New mills take time to build and commission. Can Indian sucrose supply really keep pace with ethanol demand?

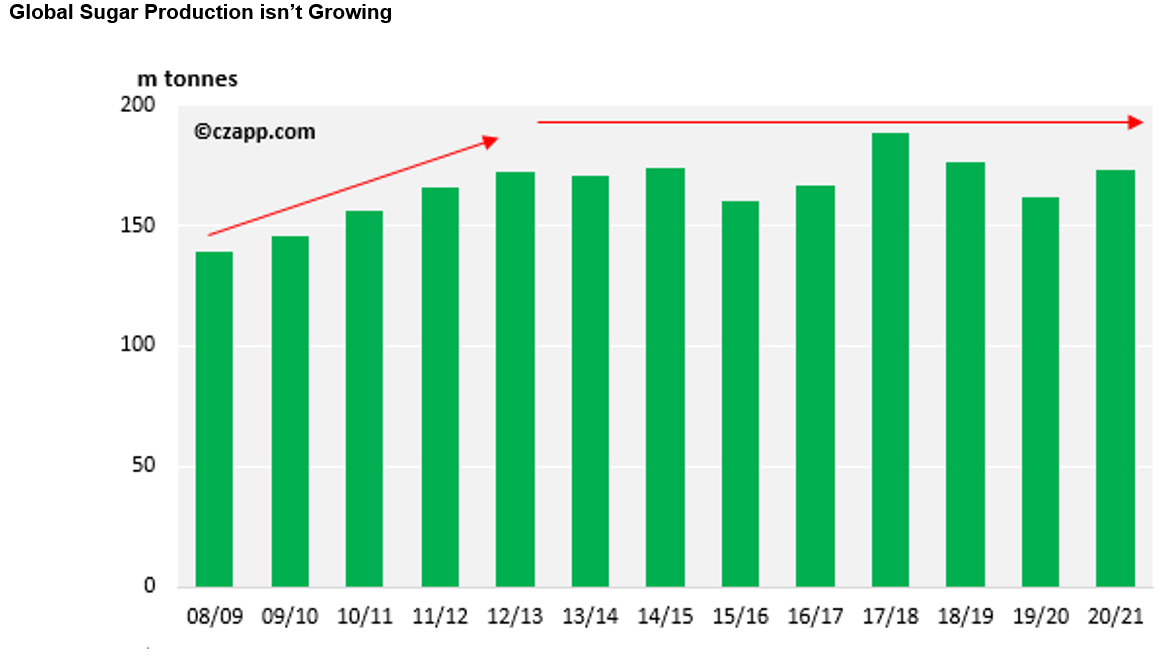

Elsewhere in the world, sugar production growth has stagnated for a decade. Returns haven’t been sufficient in Brazil or Europe or Thailand for farmers to plant more cane and beet acreage. Global sugar production peaked in 188.4m tonnes in 2017/18 and has flatlined ever since.

As we saw in 2008, the world sugar market will therefore become less well-supplied and more responsive to price. Although the market is already pricing in India’s retreat from export subsidies today, it isn’t fully pricing in its new vulnerability to production shocks. It will be unable to respond easily should there be crop failure in any of the world’s dominant sugar producers: Brazil, India, China, the EU or Thailand.

Following Europe’s reform in 2002-2008, the market rallied in 2009-2011, when the world couldn’t adapt to India’s cane failure. We don’t know what the trigger might be in 2022-2025, we only know that India’s reform has loaded the gun. A new bull market in sugar is possible once again.