- As it stands, there’s a handful of ways we deal with plastic waste.

- However, methods are emerging which mean we can utilise our waste through more forward-thinking recycling.

- Some countries are more advanced than others, but we can all learn from the leading nations.

Plastic Waste

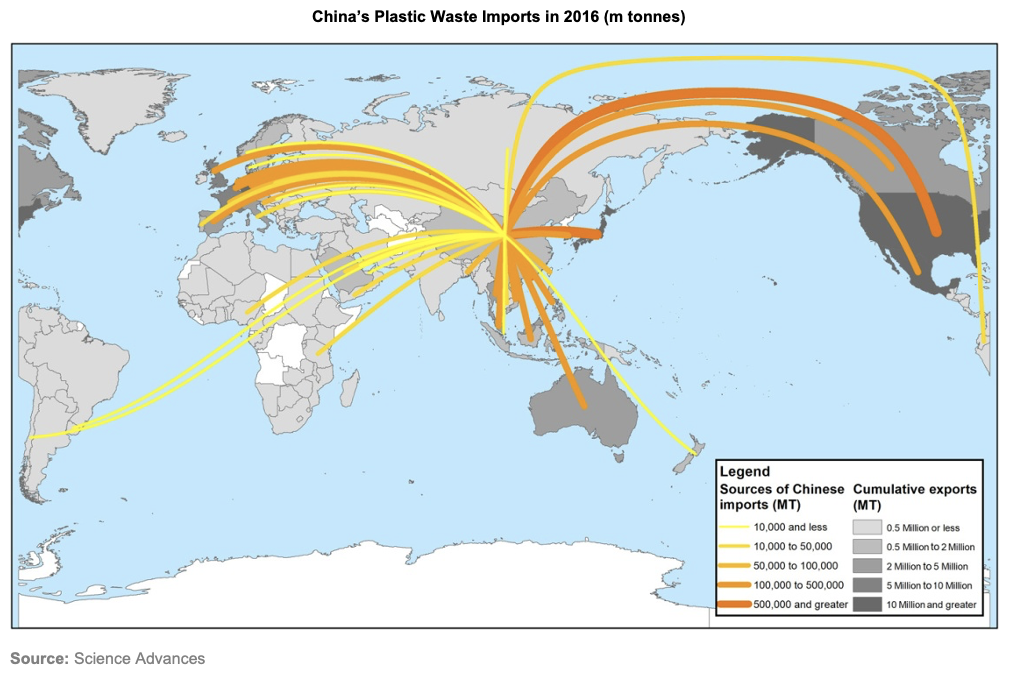

Before 2017, China and Hong Kong imported over 70% of the world’s plastic waste, even though it had inadequate recycling and incineration capacity.

In 2017, it introduced a waste import ban on 24 materials, including plastics.Some of this plastic was diverted to other countries, notably Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. However, those are now reconsidering their policies as they’ve an even smaller recycling capacity than China and don’t want to turn into the world’s dumping ground.

If the above figures are combined with the growth in plastic production and consumption, it’s clear a potentially catastrophic situation has developed.

Dealing With Plastic Waste

There are only so many ways of dealing with plastic waste at present:

1. Landfill

2. Incineration

3. Recycling

4. Dumping (legal and illegal)

5. New Technologies (e.g. biodegradable material)

On top of these, we can reduce consumption or consider alternative products, such as paper and fibres, and we can move up the ‘Recycling Resin Code Chain’.

Improvements in specifications such as thickness of the plastics and increased sorting capabilities are also worth exploring.

One of the seminal works on plastic recycling is from Geyer, Jambeck, and Law (2017). They estimate that, in the entire history of plastics, 6.3b tonnes had been created by 2015. They go on to project that 9% was recycled, 12% was incinerated and the remaining 79% (4.98b tonnes) accumulated in landfills or other parts of the natural environment.

That’s over a period of perhaps 100 years.

Another estimate is that, based on current trends, incineration and recycling could be more than 80% by 2050 (combined).

That doesn’t sound so bad until you realize that Geyer et al. estimate that, in the interim, the 4.98b tonnes will increase to a shocking 12b tonnes by 2050. So, there’s a lot more to be done…

The arguments between which is better, incineration or recycling, are complex and not always clear cut.

Incineration, with the correct scrubbers, precipitators and filters to capture pollutants, is expensive but can also be an alternative to fossil fuels. It also emits copious amounts of greenhouse gas, primarily CO2, but the method is suitable for all plastics, unlike recycling.

What makes the balance even harder to determine is the potential future development of the environmentally friendly plastic incineration, where the waste is converted into fuels and carbons, including diesel. This new technology is very expensive right now, however.

So, let’s consider some ways we can improve how we use plastic waste.

Utilising Plastic Waste Through Increased Recycling

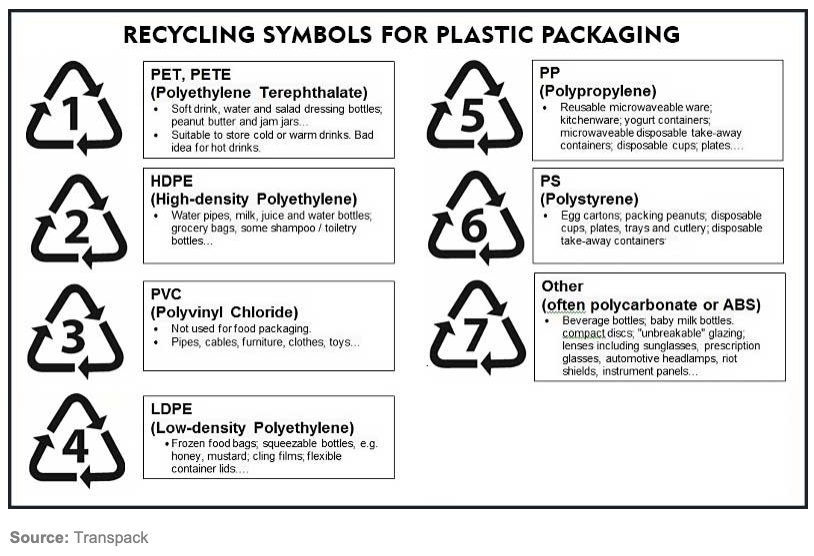

As briefly mentioned, one way we can improve recycling rates is by moving up the Recycling Resin Code Chain, from high to low codes (especially Resin Code 1, or PET).

This could come from the single largest source of plastic waste, packaging, either as a voluntary or compulsory initiative. For example, the consumer magazine Which? found that, in the worst case, 29% of one supermarket’s packaging wasn’t recyclable.

The general public has a role to play in plastic recycling too.

In Europe, some countries have high recycling rates. According to Eurostat (2018), the EU average is 42%. Lithuania (69%) and Slovenia (60%) are the best, whilst France (27%) and Malta (19%) are the worst. Following the example of the leaders would be a significant improvement. Note, however, for overall recycling, Germany and Austria top the chart.

The public can also assist if labelling was clearer. One good example is the UK, which is simple and clear.

Even where packaging can be recycled, it sometimes isn’t.

In the BBC series War on Plastic, it proved almost impossible to separate the cardboard and plastic components, and yet, these sandwiches were labelled ‘Widely Recycled’. That’s not in the spirit of the labelling scheme, but the industry has promised improvements.

Utilising Plastic Waste Through Improved Technology

Technology also has a role to play.

One good example is PRISM (Plastic Packaging Recycling using Intelligent Separation Technologies for Materials). Six years in the development and supported by Innovate UK, WRAP and PRISM partners, it uses coded fluorescent labels on plastic packages that can be read by high-speed optical sorting machines.

The process is complimentary to current Near Infrared (NIR) technology.

In the UK, recycled food grade plastic must be made from greater than 99% of the previous food packaging. PRISM achieves this, saving products not being used as effectively as possible or going to the landfill.

Other new technologies include:

1. Agilyx (US) converts the ecologically undesirable polystyrene (PS) into a liquid called ‘presto-chango’.

2. Saperatec (Germany) has developed specialized micro-emulsions (surfactants) that reduce surface tension and can separate aluminium and cardboard from plastic layers.

3. Ioniqua (Holland) uses a magnetic field and smart liquid to change the properties of plastics. In the case of PET, the liquid removes colorants and contaminants, leaving a usable raw material.

Final Thoughts

Plastics have many advantages, but their disposal or reuse has become a major problem and clear thinking is required to solve it. Every part of the supply chain has a role to play.

Czarnikow can structure tailored risk management solutions on both recycled and virgin packaging. If you’d like to explore how Czarnikow can help you manage your price risk management, please talk to Maximilian Kirby (MKirby@czarnikow.com).

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…