In the previous two reports, we discussed the importance of choosing the right synthetic fertilizer, especially within the framework of ‘the Four Rs’ (namely the Right Fertilizer and Right Application Rate).

We’re now going to concentrate on the third of the Four Rs: Right Timing.

In this discussion, comments are in relation to arable crops (excluding rice). Although this week’s conversation is about the use of synthetic fertilizers, many of the principles involved are relevant to the use of agrochemicals, seeds, and other inputs.

An Analogy from a Chef

Raymond Blanc OBE runs the two-Michelin-starred restaurant, Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons, in Oxfordshire, UK. He has made numerous TV shows and will be recognised by many of you.

And it so happens that his genius as a chef is a useful analogy and introduction to the subject of timing in Sustainable Agriculture (SA).

Raymond is currently serving his ninth year as the President of the Sustainable Restaurant Association. He understands that producing world-class dishes starts with having the right raw materials that are seasonal and fresh.

For vegetables, local fruit and herbs, this means managing the restaurant’s extensive gardens. In doing so, he’s knowledgeable about the produce in the gardens and elsewhere. He knows the best produce for different soil types and climates. He even accepts that there are some matters beyond his control, such as frosts and droughts, meaning he has to be adaptable.

Once in the kitchen, there’s a perfect harmony of art and science. Timing is everything and to bring the final dishes together, often with many components, requires understanding, technique and skill. Ingredients and seasonings have to be used in the right order to reap the perfect result. One dash of seasoning at the wrong time, one lapse in concentration to over-reduce a sauce, one scallop seared for too long is unacceptable.

Raymond has also learned from others by experimentation and by educating himself. And finally, there’s little waste: trimmings and bones are utilised to make delicious stocks and soups.

Timing in Sustainable Agriculture

The challenges faced in the Raymond Blanc analogy are similar for arable farmers.

The impact of poor timing and ignoring seasonality in fertiliser application can be just as serious on wastage and greenhouse gas emissions as using the wrong application rate discussed in the last report. In both cases, the aim is to achieve proximity to the Theoretical Best Performance (TBP). Leaching, volatilisation to the atmosphere and runoff are all potential adverse consequences of poor timing.

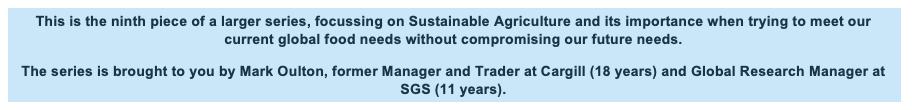

The growing plant has different needs for nutrients depending on the time of year (seasonality). Although each crop is different and there are variations between spring and winter sown, it’s possible to make some generalisations.

The above chart shows how the typical nutrient uptake for cereals and is relevant whether establishment was in the winter or the spring.

There are several important considerations. The first relates to leaching and, in particular, nitrogen and sulphur, which are prone to leaching.

For nitrogen, timing is critical to avoid leaching and the applications in cereals are normally split two, or preferably three times, to match the needs shown in the above chart. It follows that the second of three applications should be the heaviest. The final (or even a fourth application) has a significant effect on grain protein/nitrogen. This increase may be desirable for certain types of wheat as it improves the bread making quality. It is undesirable in malting barley as maltsters desire the lowest grain nitrogen possible and similarly for wheat in biscuit production, high protein levels are not sought.

Sulphur should be applied wherever possible in the early to middle stages of vegetative growth. Potash needs to be in situ well before the spike from early vegetative growth up to the end of flowering.

It’s common for winter planted crops to apply the potash and phosphate in the late autumn/early winter, avoiding periods of heavy precipitation and runoff into the water course. This is partly a convenience to reduce the heavy spring workload. However, the current practice in parts of the US of applying injected anhydrous ammonia with a nitrification inhibitor on maize in the autumn conflicts with SA principles because the nitrogen can easily be lost to the plant in wet and early spring conditions. Even very early spring applications of anhydrous ammonia carry a different risk as an ensuing dry period could make the nitrogen unavailable to the plant.

Volatilisation of nitrogen is a serious problem because of its consequences for greenhouse gas production. It’s best controlled by the type of nitrogen used (ammonium nitrate, for example, is better than urea in later applications, especially without urease inhibitors and in warm-hot conditions). Some common sense can also help, such as not applying urea at the hottest part of the day or waiting for a cooler spell.

Knowing Plant Needs and Optimisation

The main raw material for crop production is the soil. Adaptability is vital. Trying to force production from a soil in poor condition is a worthless and potentially environmentally damaging task. Each soil type also has its own relevant timings and attributes. Fortunately, as with assessing the right fertiliser rate, timing suggestions are included in many of the available models.

Similarly, weather can play a part in the decision-making process and, with modern long-range weather forecasting systems available, these are useful timing tools.

Knowing the nutrient requirements (ingredients) and timings for each intended crop is vital and the nutrients, correctly timed, also play a secondary role: ensuring plant health to mitigate against disease and insect attack that rob yield.

The above relates to cereals, but each crop has its own peculiarities. For example, tuber crops, such as potatoes and cassava, require large amounts of potassium during the bulking stage. Oilseeds, such as sunflower and oilseed rape, benefit the most from any application of sulphur early at the establishment phase, and so on.

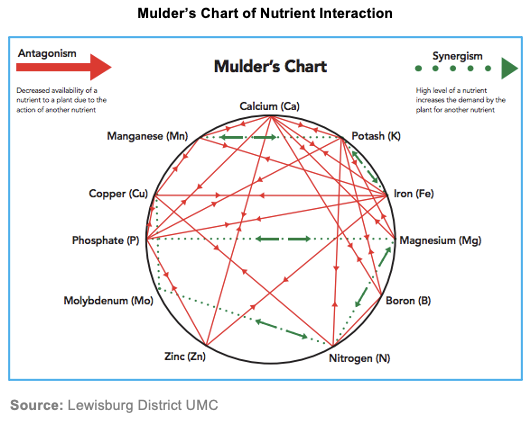

The ‘ingredients’ on the crop are supplemented by ‘seasonings’, the latter of which come from the wide range of micronutrients (around 20 important ones). It’s complicated because, just as in the kitchen, some seasonings and ingredients are natural pairings with the raw materials (synergistic) and some aren’t (antagonistic). The situation is the same in agriculture.

The Perfect Dish

To complete the analogy, the perfect dish will have wonderful tastes and aromas (analogous to quality from correct growing, such as high seed weights and/or oil content) and there will be enough for it not to be taken off the menu (analogous to quantity from high yields).

Waste should be minimal.

Timing in Sustainable Agriculture is about working in harmony with nature.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- Sustainable Agriculture: Arable Farming

- Sustainable Agriculture: Arable Nitrogen Use

- Sustainable Agriculture: Tackling Fertilizer Waste Head-On