The Origins of Sustainable Agriculture

SA isn’t new. The earliest farmers knew that if they didn’t move their grazing animals to new pastures and let old ones recover, disaster would follow. They knew that if they didn’t prevent flooding, they may not get a crop that year. And they knew that if they practised monoculture and didn’t rotate crops, yields would eventually decline because of a lack of nutrients or a build-up of pests and diseases.

With the advent of high input/high output “industrial farming” in the 19th and 20th centuries, many of these simple ideas were forgotten or tools developed to counteract problems such as the intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides, development of higher yielding varieties, greater mechanization, and the use of irrigation. It gradually became clear that this “industrial farming” was neither meeting current needs of many of the world’s poorest countries and most certainly not securing our future needs as issues such as desertification, soil erosion, salinity from over-irrigation, loss of soil fertility, scarcity of water, and many others, became apparent.

Initial efforts and research into SA were heavily focused on agricultural units of production, the farm, but more recently (from the 1960s), scientists and other academics have focused on the whole ecosystem.

Producing in a more sustainable way is challenging, but it becomes immeasurably more difficult when the global population could exceed nine billion by 2037 (from a current level of 7.8 billion). Of those nine billion, some 40% will be small farmers.

The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) in a major 2017 report concluded that the world is not on track (actually, not even close) to meet the zero-hunger target by 2030 called the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). In fact, in the previous three years prior to the report, food insecurity had got worse and the damage to both food production and distribution from COVID-19 will likely have caused a further deterioration.

Global Warming

Most people are aware of global warming from its extensive media coverage. It is largely caused by the emission of greenhouse gasses (GHG) such as carbon dioxide and methane. Global warming is not only threatening because of increases in temperature, but also because of increasing extreme climatic events.

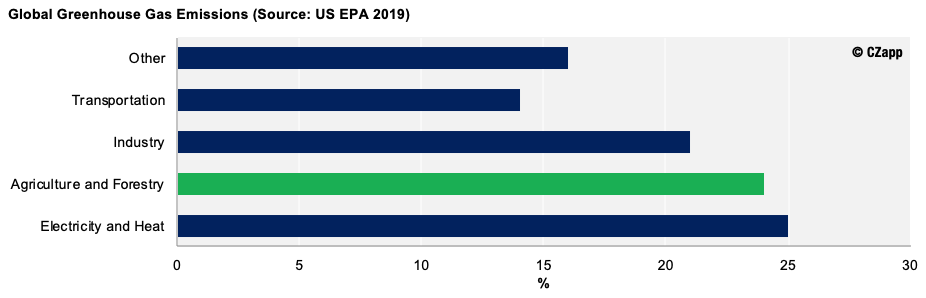

Although agriculture (and forestry) is an important contributor to global warming, it suffers disproportionately from it because it reduces the farmers’ ability to generate money for the crops they sell or, in the worst case, stops them having sufficient food on their own tables.

Global agriculture occupies around 35-40% of the world’s land area and is a major contributor to environmental risks. It uses 70% of all the globally withdrawn fresh water and

large quantities of fossil fuels which are used to produce fertilizer and other agricultural inputs. The possibility of increasing the land area in any sort of environmentally acceptable way is limited because it means using more marginal and less productive land, and every extra hectare contributes to more environmental pollution. This is especially true if it involves deforestation.

Deforestation is particularly damaging because plants and trees are able to take up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store carbon in their biomass and underground cavities called ‘sinks’ rather than releasing the carbon into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases (GHG); this process is known as ‘carbon sequestration’. The ocean also has important carbon sinks.

The first point is to recognize that we must find a method to avoid placing the world into catastrophic and irreversible environmental instability. Any attempts at SA need to adhere to this unavoidable framework. There is a reasonable scientific consensus that global climatic stability is achievable below around 350-450 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere. This equates to a maximum global temperature rise of 1.5 °C, also generating around 400 ppm of CO2, and similar to the 2015 Paris Climate Accord of no more than 2 °C above the

1880 pre-industrial level. The Accord was signed by 189 countries. At current levels of progress, that level would arrive sometime between 2030 and 2050. This is often called the ‘planetary boundary’ or ‘tipping point/point of no return’.

So far, even with the bonhomie of the Paris Climate Accord, although a significant step, progress has been insufficient to meet these targets.

A Controversial Solution, or an Unavoidable One for Agriculture?

In 1798, Thomas Malthus, wrote his famous Essay of the Principles of Population. Although a complicated and politically charged treatise and still referenced by supporters even to this day, the conclusion, without any knowledge of global warming, was that eventually the global growing population would exceed agricultural capacity.

He was a little coy as to when such a catastrophe would occur and even recognized that science and technology could prevail, which it did. So far, his theories have been disproven.

The green revolution, leaps in science and technology, mechanization (etc) have all proved our capability to keep up. It’s useful to remember the Malthusian model because today we are going to have to use education, science, and technology, to create a ‘second green revolution’ and SA will have an important role in this.

While recognizing the needed reduction in GHG from the role of industry, and the need for more environmentally sensitive power sources such as wind and solar, SA has a centrepiece role to play in reducing GHG and the prognosis is not as gloomy as previously suggested. This is in spite of the constant seemingly conflicting needs of protecting the environment and feeding the world.

What Comes Next?

In the next Opinion, we will demonstrate how SA can in some cases actually improve agricultural yields and introduce the more radical concept, developed from 2000 onwards, of Sustainable Intensive Agriculture (SIA).

We will also examine what makes a good and relevant SA programme for the agricultural supply chain and which parameters are the most meaningful, measurable, and impactful. The discussion will then turn to the role of the consumer, who, we will prove, is currently confused by SA labelling.

SA is not particularly about production methods such as organic, farm fresh, free range, GMO free, etc. All these methods may well have relevance in SA both directly, and often substantially, from reduced inputs, or indirectly from reduced toxicity or other perceived health benefits.

The use of SA is much more about how we use the available tools and concepts in a holistic way to feed the world and protect the environment.

Other Opinions Written by This Author…