Insight Focus

Freight prices have shot up since the Houthis began attacking ships in the Red Sea, causing mass re-routing. However, this is not the only factor causing prices to rise.

What is Happening with Freight Price?

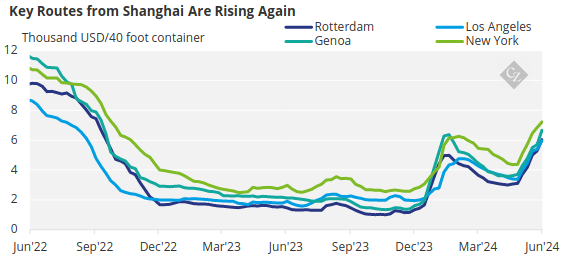

After a lacklustre few years with declining freight prices, suddenly 2024 has seen the cost of routes surge again to pandemic levels.

Source: Drewry

Although not quite at the heady USD 20,000 peaks seen during the pandemic, several factors are pushing rates ever higher.

One issue to look out for is the disconnect between spot rates and long-term contracts. Long-term contracts for the year traditionally close in May – which means shippers have just signed on to fixed rates while costs continue to spiral. Already, charter rates are rising as vessel owners take advantage of the current environment, according to Alphaliner and Clarksons Research.

The disconnect between contract and spot rates means there may also be a repeat of the contract cancellations seen during Covid. Food and beverage companies importing and exporting goods will have to keep a close eye on several factors in the market that will impact shipping price and reliability.

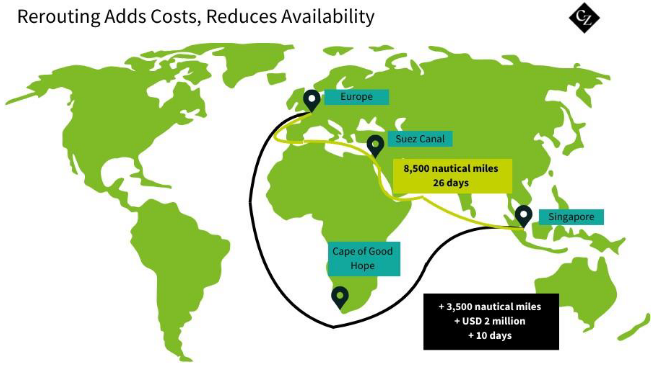

1. Conflicts

Right now, the single biggest cause of freight rate rises is the conflict in the Red Sea. As vessels largely avoid the Red Sea, the fastest route from Europe to Asia is around the Cape of Good Hope. This adds 10 days, 3,500 nautical miles and costs of at least USD 2 million for box carriers.

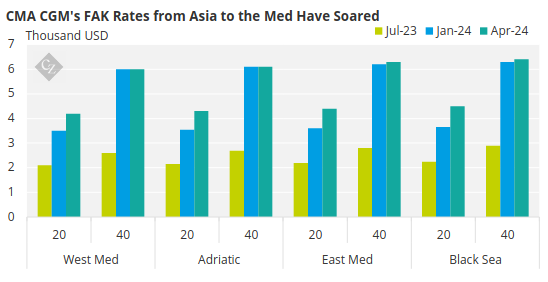

The carriers are imposing much higher rates, particularly on the routes impacted by the Red Sea. For instance, CMA CGM is now charging about double its July 2023 rate for a 20-foot container from Asia to the Mediterranean and Adriatic.

Source: CMA CGM

And even though the Black Sea is deemed to be less risky than at the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war, there are still regular attacks on ships – albeit no direct attacks on commercial vessels. Instead, Russia tends to focus on Ukrainian port infrastructure, while Ukraine attacks Russian vessels it suspects of carrying weapons.

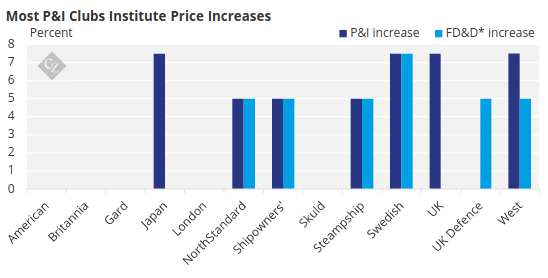

As a result, insurance for shipowners is getting more expensive, which in turn is pushing up costs for charterers. And while some P&I Clubs this year refrained from across the board increases, there are certain conditions.

*freight, demurrage and defence

For instance, Britannia has said that there will be no mandatory increase in deductibles but this will be reviewed depending on risk and record. In addition, Gard will assess members individually to decide on renewal increases, taking into account price levels and loss records.

2. Weather

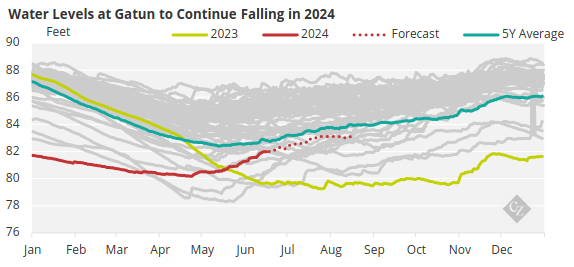

Water levels at the Panama Canal are recovering – although not quite as fast as many would have hoped. As of mid-June, levels have almost recovered to the five-year average.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

As a result, the Panama Canal Authority has managed to increase drafts and the number of daily transits has risen. As of July 11, daily transit numbers will rise to 33 from 32, followed by another increase to 34 as of July 22.

A draft increase to 46 feet from 45 feet will be effective as of June 15.

Although this recovery is encouraging, this is unlikely to be an isolated weather-related incident to impact shipping. This May, extensive flooding in the south of Brazil had huge impacts on port operations.

Not only did currents in the Rio Grande increase to over 5 knots, but the flood waters ultimately drained into the bar channel of the river, which is a crucial passage for grains, fertilisers and containers.

Although berthing at the Tecon container terminal continued to operate, drafts were decreased to 42 feet and all vessel manoeuvres were restricted to daylight hours only. Brazil is not alone. In fact, a 2023 research paper found that “port-specific risk” is estimated to cost USD 7.6 billion per year due primarily to cyclone wind and flooding. In particular, it noted that 21 ports – including Houston, Shanghai and Mexico’s Lazaro Cardenas – are each at risk of damage in excess of USD 50 million per year.

While weather issues are not currently impacting freight prices, they are likely to be a problem that will stick with the industry for the long term.

3. Regulations

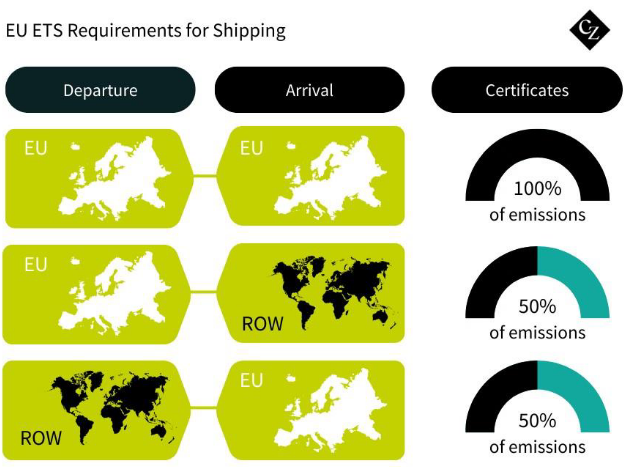

Some highly publicised emissions regulations coming into force for the shipping industry are going to impact on freight prices. One of the most discussed is the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which requires shippers to declare emissions starting this year.

From this year, shippers are required to surrender emissions allowances (EUAs) matching 40% of their total emissions from voyages within the EU, but also those voyages that begin and end in EU waters. The surrender requirement for shippers goes up to 70% for 2025 emissions and reaches 100% in 2026.

Unlike certain other sectors in Europe, there will be no free allocations for shipping. This means the shipping industry will have to purchase allowances covering all their eligible emissions to surrender at the end of the year.

There is a high likelihood that these additional costs will be passed on to customers in the form of higher freight rates. Not only this, but other countries are looking at implementing their own ETS systems, or expanding them to include shipping, meaning higher costs are a definite long-term feature of the market.

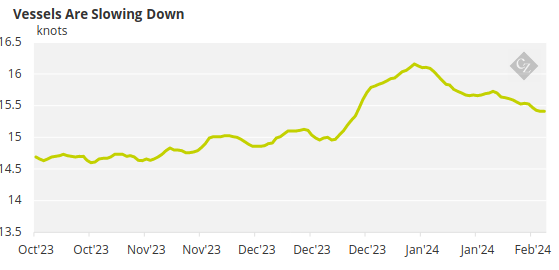

In order to mitigate the costs of these certificates, shipping companies are trying to keep emissions lower. In the long term, this means innovating with new fuel types, but in the short term, certain measures such as slow steaming can help limit emissions.

But as vessels get slower, global availability decreases. With limited supply, prices will rise. This is another factor that will contribute to a long-term freight price increase – particularly during high-demand periods.

4. Strikes/Port Congestion

Last June, 29 ports on the US West Coast finally reached an agreement with labour unions for a six-year contract after 13 months of strikes, walkouts and severe disruption to operations. The impact was particularly felt by Asian markets. West Coast ports account for roughly 60% of Asian imports to the US.

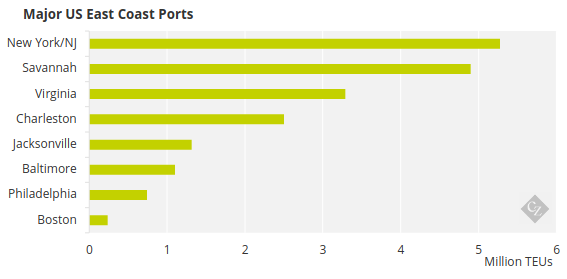

Now, East Coast ports are facing the prospect of prolonged strikes after their own labour contracts with workers came up for renewal this summer.

Already, the situation is fraught after the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), which represents the workers, halted talks with the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents the port operators. The reason for this was due to a disagreement over a new drive for port automation, which the ILA says will lead to job cuts.

The largest US East Coast ports at New York/New Jersey and Savannah handle around 5 million TEUs of containers every year.

This is not limited to just the US. In Germany, the dockworkers union Vereinte Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft (ver.di) called for strike action this week after pay negotiations broke down.

A strike was planned by French stevedores at all French ports during June due to unresolved labour condition and pension reform issues. The strike was suspended until September due to the snap elections that were called in the country this month.

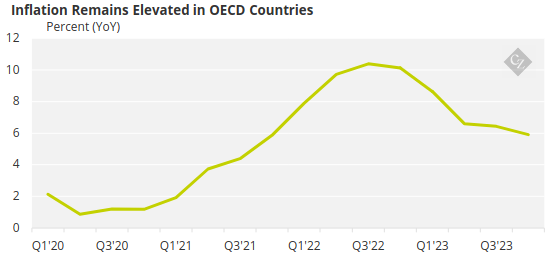

As the cost of living continues to increase, it is likely that we will see more of these kinds of labour disputes. Although lower than it has been, inflation has remained at around 6% across OECD countries.

Source: OECD

5. Supply and Demand

Supply and demand are both big drivers of freight prices. A huge boom in shipbuilding in the early 2000s resulted in a supply glut when global demand dropped, which weighed on prices.

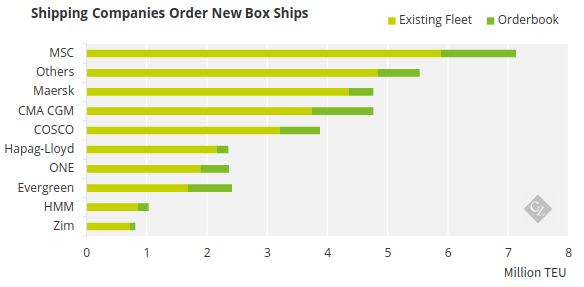

Right now, more supply is coming online. The TEU on order now accounts for almost 20% of current capacity.

Source: Alphaliner

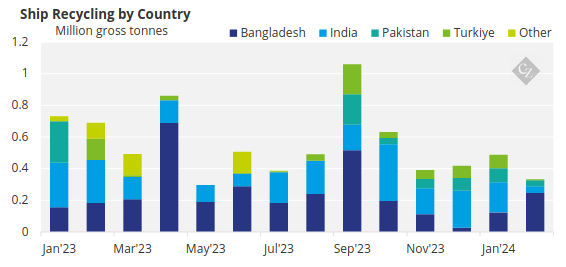

Ship recycling is also getting lower, which points to an increase in net supply. However, these ships are also ageing, which could present a sudden problem for the industry.

Source: Lloyd’s List

And demand also looks like it’s picking up enough to absorb this additional supply. Although stubbornly high inflation remains in the US, consumer spending is starting to increase.

Source: BEA

This should rise even further if the Fed cuts interest rates, which it is slated to do at least once this year.

Peak season for containers is also well underway, which refers to a high demand restocking period among key western markets. Right now, US inventory to sales ratios are lower than normal, which could lead to much higher demand than usual.

Source: St Louis Fed

Concluding Thoughts

- While there is at first glance enough shipping capacity, this is being throttled by geopolitical events.

- The conflict in the Middle East shows no sign of stopping.

- While El Nino is now turning to La Nina, there is likely to still be huge weather-related disruption as the global climate changes.

- Emissions regulations will limit capacity even further as vessels slow steam and shipowners navigate compliance issues.