Insight Focus

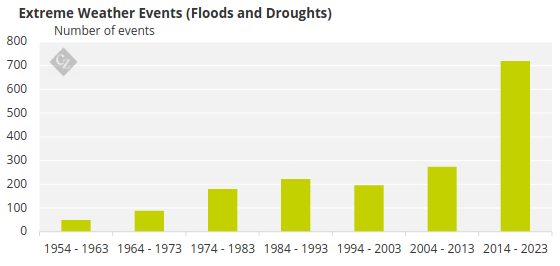

Extreme climate events increased by 162% in the past ten years and have caused serious losses to agribusiness revenue in Brazil, with an impact on rural insurance and repercussions on food security.

Climate Change Causes Losses in Agriculture

Rural producer Graziele de Camargo, from Rio Grande do Sul, is still counting losses from the floods that devastated 70% of the state last month. Graziele lost more than half of the soybean crop, which was being harvested when the rains arrived. She is far from alone.

The floods in the South caused losses of more than BRL 1.3 billion to agribusiness – and reignited an important discussion about the impacts of climate change in the countryside.

Graziele de Camargo examines soybeans after the flood. Source: Graziele de Camargo

This debate, however, is not new. It was just asleep. Ten years ago, a group of researchers developed the project “Brazil 2040: Scenario and Alternatives for Adaptation to Climate Change” and sent it to the government.

The study, discontinued in 2015, predicted an increase in rainfall in the South and droughts in other regions, which was indeed confirmed. In the last decade, the number of extreme weather events increased by 162% compared to the previous ten years.

Source: National Geological Service

Risk Mapping Tools Prove Essential

There is a lot that can be done, from investments in more resilient infrastructure to sustainability measures. What is missing is getting our hands dirty. “Early warning systems and water resources management, for example, can reduce the damage from climate shocks,” says environmentalist Natalie Unterstell, one of the authors of the “Brazil 2040” study.

Agricultural risk mapping tools are also essential, and these have attracted the attention of public authorities. In recent years, Embrapa has intensified the updating of the Agricultural Climate Risk Zoning (Zarc), a tool that provides the most appropriate planting windows for each crop and location based on analyses of climate and soil patterns.

The ideal cultivation period for species such as wheat, oats and rye were revised depending on changes in the climate pattern and other species, such as onion and açaí, were included. At the same time, field work continues to map changes in climatic conditions that affect the soil.

Embrapa technicians analyze soil conditions. Source: Embrapa

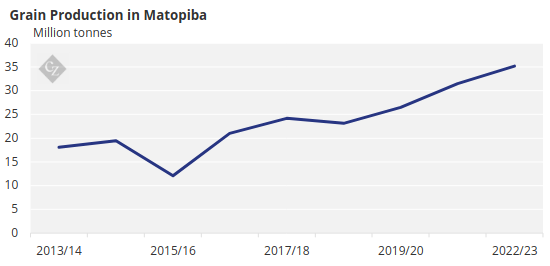

“In Western Bahia, for example, our technicians have been observing a reduction in the window for planting the second grain harvest due to the lack of rain,” says José Eduardo Boffino de Almeida Monteiro, agronomist and researcher at Embrapa. The region, which is part of Matopiba (Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia), has been taking off in soy and corn production, so any disruption requires increased attention.

Source: Conab

Financial Losses

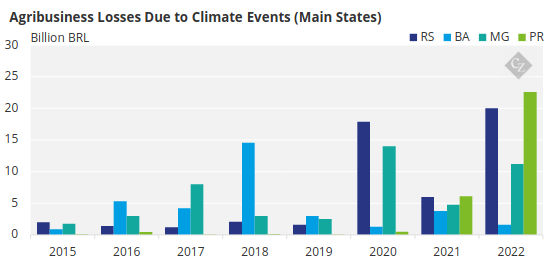

In the Northeast, Bahia has been leading the losses in agriculture caused by the climate. Between 2015 and 2022, the State recorded losses of BRL 34.7 billion. Even so, it is still a milder scenario than that of Rio Grande do Sul, one of those most affected in the last decade, with more than BRL 50 billion in losses due to floods and droughts.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Regional Development

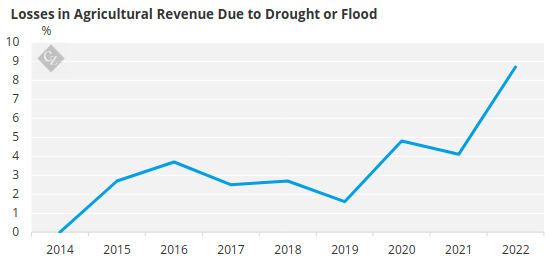

In 2022 alone, climate change caused a loss of 8.7% to gross agribusiness revenue, in an escalation that has been increasing in recent years.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture

Rural Insurance Insufficient

There is another important point to be considered, which also concerns food security and the rural producer’s permanence in the field. What risk management instruments are available to farmers? And to what extent will insurers and rural producers be able to sustain ever-increasing losses?

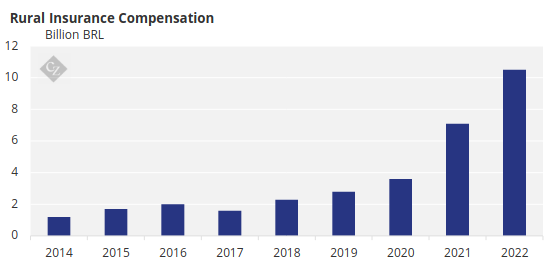

With the increase in crop losses, compensation payments have increased. In 2022, BRL 10.5 billion in insurance was paid, compared to BRL 7.1 billion in 2020. The problems in the South should add more fuel to this fire. As a result, insurance is likely to become more expensive and, therefore, less accessible to the farmer.

Source: CNseg

“It is already becoming difficult to insure the entire harvest, precisely because of the losses and the financial impact on insurance companies,” says farmer Graziele de Camargo, who has less than 20% of the harvest covered against risks.

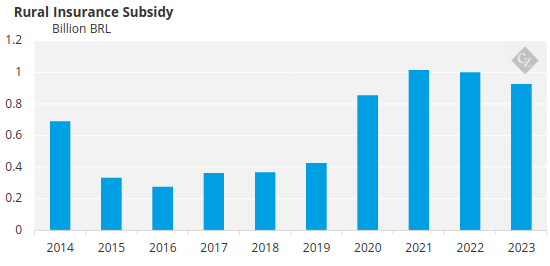

On the government side, which subsidizes rural insurance, the situation is not much better either. The value of the subsidy this year should be similar to that of 2023, when almost BRL 930 million were released, well below the BRL 2 billion requested by the rural sector. In Brazil, government resources cover up to 40% of insurance for most crops – in the case of soybeans, the limit varies from 20% to 30%, depending on the region of the country.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture

In a situation marked by limited access to risk mitigation instruments and an intensification of climate change, it is not unlikely that some farmers will end up leaving the industry entirely. In the South, this is precisely the expectation. “The high level of debt of producers, who have been suffering from droughts and floods for three years, is making some rethink their activity and look for other means of living,” says de Camargo.

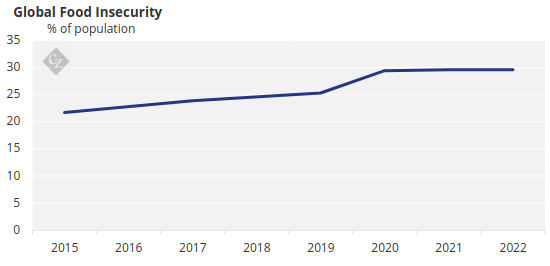

Food Security at Risk

These issues are particularly concerning when warning lights are already flashing in relation to more persistent increases in food inflation and food security. An FAO study shows that the increase in food prices exceeds that of general inflation in half of the 166 countries analyzed.

Source: FAO

FAO, the World Bank and other international organizations have been working on sustainable agriculture initiatives in Brazil and other countries with the aim of making the activity more resistant to climate change. Technology has also helped in this regard.

There is no shortage of good examples around the world. In India, AI is being used to make more accurate weather forecasts and send information about planting and harvesting to insurance companies.

In Brazil, Embrapa has been developing seeds adapted to less favorable climate and soil conditions. A good example is tropical wheat. Other research centers and universities have been looking at solutions for adapting agriculture to climate shocks. It has become clear that it is time to step on the accelerator.