Insight Focus

The global container ship fleet has reached an overall capacity of 30 million TEUs. This growth is attributed to a surge in newbuild orders prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic and an aggressive acquisition strategy from several container carriers.

Next Milestone Could Be Around the Corner

The global container ship fleet has achieved a significant milestone, reaching an overall capacity of 30 million TEUs. But with nearly 25% of the active fleet currently on order, it’s only a matter of time before the container ship fleet ascends to new heights.

Trevor Crowe, Director of Clarkson Research, a division of the UK shipbroking firm Clarksons, noted, “Looking ahead, another wave of orders since June (totalling 2.4 million TEUs and counting) has pushed today’s orderbook to 7.4 million TEUs. That’s a strong start on the road to 40 million TEUs, so the next container ship fleet milestone might not be so far away.”

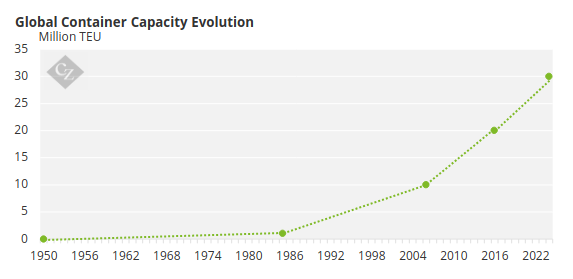

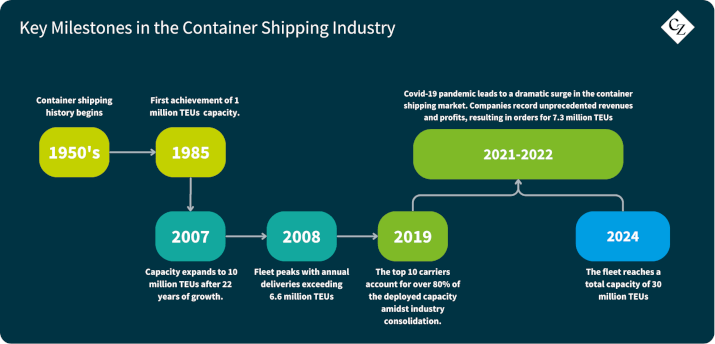

To appreciate this achievement, it’s important to examine the growth trajectory of the box ship fleet over the years. Container shipping history began in the 1950s, taking about 35 years to reach its first milestone of 1 million TEUs in 1985.

After 22 years, this capacity had expanded to 10 million TEUs by 2007. After the 10 million TEU milestone, the pace quickened dramatically as companies began constructing more and larger vessels. In just nine years, the fleet added another 10 million TEUs, and it took only eight more years to reach the current capacity of 30 million TEUs.

Crowe emphasized the trend towards larger ships over the years: “The size of the largest vessels delivered to the fleet has more than tripled, growing from 4,614 TEUs in 1985 to 15,500 TEUs in 2007,” he pointed out.

Liner Orders Strong Even During Recession

The early 2000s economic boom, driven by China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, spurred heavy investment in new container ships, according to Clarkson’s report, which noted that between 2006 and 2015, the fleet averaged 1.4 million TEUs in annual deliveries, peaking at over 6.6 million TEUs in 2008, just before the global financial crisis, accounting for 60% of the fleet at that time.

Although the container market was subdued during much of the 2010s, liner operators continued placing newbuilding orders amid industry consolidation, with the top 10 carriers accounting for over 80% of deployed capacity by 2019.

The Covid-19 pandemic then catalysed a dramatic market surge. In 2021 and 2022, container shipping companies recorded unprecedented revenues, skyrocketing earnings and profits, leading the majority of them to invest significantly in new vessels to enhance their future operational capabilities. This period saw orders for 7.3 million TEUs, including a notable increase in “green” ships designed for alternative, environmentally friendly fuels.

MSC Leads the Market

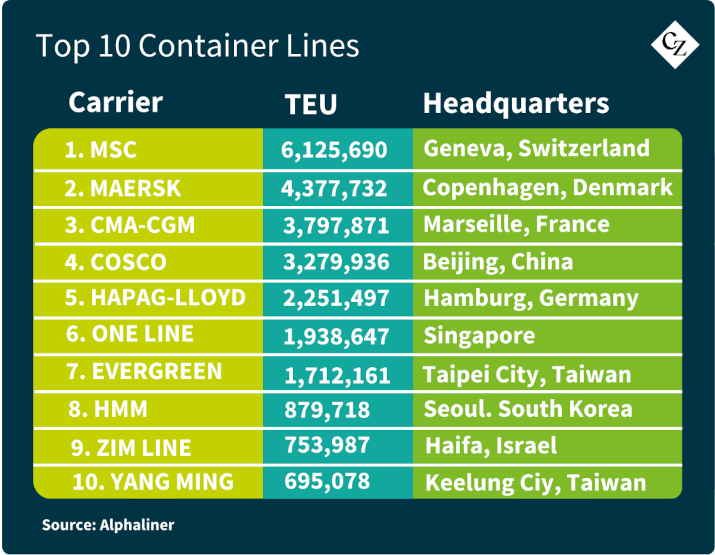

The distribution of the container ship fleet has also evolved in recent years. As of January 2022, Swiss/Italian ocean carrier MSC dethroned Danish shipping powerhouse Maersk after more than 25 years at the top of the rankings.

MSC currently commands a 20% share of the global container market, with 860 vessels and 6.1 million TEUs in capacity, alongside the largest orderbook in the industry. Maersk follows with 715 ships and a capacity of 4.4 million TEUs, while French liner operator CMA CGM rounds out the top three with 646 vessels and 3.8 million TEUs.

Chinese shipping giant COSCO ranks fourth with 510 vessels and an overall capacity of 3.2 million TEUs, followed by German box carrier Hapag-Lloyd, which operates 293 vessels with a capacity of 2.6 million TEUs. The remaining players in the top 10 include Singapore-based Ocean Network Express (ONE), Taiwan’s Evergreen and Yang Ming, South Korean HMM, and Israel-headquartered ZIM.

It is important to note that the total market share of the 10 largest container shipping companies approaches 85% of global container capacity, meaning they essentially define the rules of the game and set the tone for global trade.

Aging Fleet Could Hinder Fleet Expansion

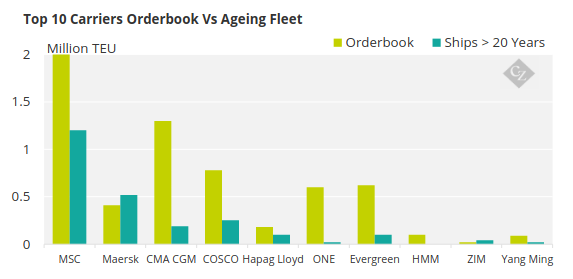

One thing that could potentially put brakes on the aggressive expansion of the global fleet is the number of older vessels. It’s crucial to note that not every new vessel contributes to fleet growth, as many ships are ordered to replace older ones. According to Alphaliner, the 10 largest container carriers are currently operating 683 vessels aged 20 years or older, representing over 2.6 million TEUs in capacity terms.

Source: Alphaliner

If we consider 25 years as the typical lifespan for a cargo vessel, these figures suggest that 44% of the combined orderbook could be used from container lines to rejuvenate their fleets, replacing these aging ships, rather than for expansion.

The proportion of older ships varies significantly among the top 10 liner operators. MSC has the largest orderbook and the greatest number of old ships. While the liner operator is building 137 ships, amounting to nearly 2 million TEUs, it also still operates 315 ships which were built in or before 2004.

In contrast, HMM operates only one aged vessel, a chartered multi-purpose ship, indicating that all 13 ships in its orderbook are aimed at expansion.

Ocean Network Express (ONE) has a low ratio of aged vessels to its orderbook at 6%, reflecting its strategy for fleet growth and larger market share in the market. The same is true for CMA CGM and Evergreen, which have aged vessels accounting for around 17% of their orderbooks.

Notably, Maersk is the only liner operator that has not ordered sufficient new ships to offset its ageing tonnage, although it has committed to a fleet renewal programme of 800,000 TEUs over the coming five years, including 500,000 TEUs of chartered vessels.