Insight Focus

Brazil took a big step by approving the law that regulates the carbon market. Now, the government is preparing to define the sector’s operating rules and decarbonization goals, which should open opportunities for sectors such as biofuels and renewable energy.

Regulation Creates Business Opportunities

After approving the law that regulates the carbon market at the end of last year, Brazil is preparing to create the necessary mechanisms for the system to come into force. The market is already beginning to move to participate in discussions and take advantage of business opportunities.

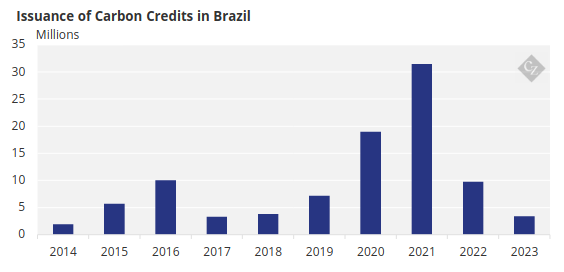

The leap in carbon credit negotiations is expected to be gigantic. The country is expected to go from moving USD 1 billion per year in carbon bonds to USD 50 billion in 2030, according to the Ministry of Finance. There will be more than 30 million credits negotiated per year, 10 times the current volume.

Source: FGV.

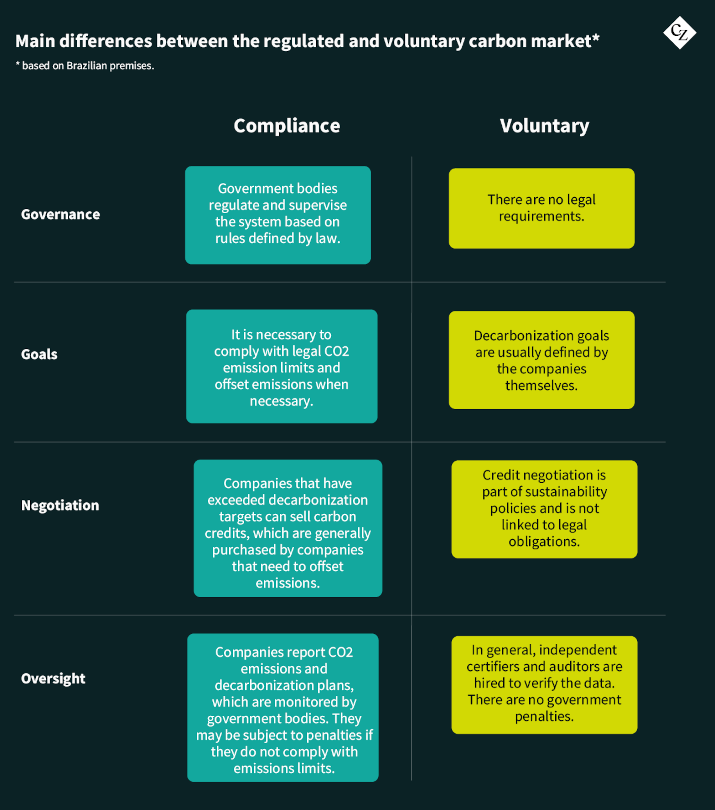

Today, carbon credits are traded on the voluntary market and are not subject to legal obligations or periodic monitoring, which reduces the pace of negotiations and the value of assets.

Natural candidates for issuing carbon credits, sectors such as biofuels, renewable energy and bioinputs are already eyeing the opportunities. But there are still challenges to be overcome, including the creation of a broad government database for the analysis of CO2 emissions.

We talked about this topic with Matheus Soares, energy, sustainability and government relations partner at Barral Parente Pinheiro Law Firm.

Matheus Soares

What will be the step-by-step process for structuring the carbon market?

The government defined a schedule for the gradual implementation of the measures necessary to structure the market. The first step is the creation of the management body that will be responsible for ensuring that the Brazilian Emissions Trading System (SBCE) is implemented.

The SBCE will define the rules and governance for the issuance and trading of carbon credits. A regulatory body will also be created, which will have a series of complex responsibilities. The structuring of this body is expected to take one to two years.

What will be the main responsibilities of the regulatory body?

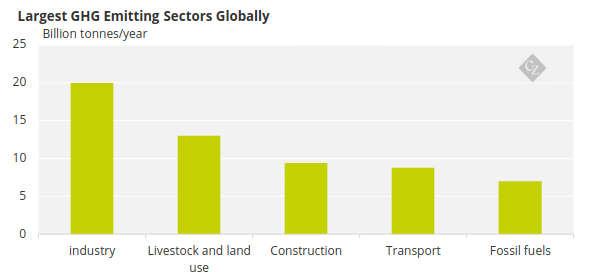

There are several responsibilities. One of the biggest challenges will be defining which sectors will be regulated and how this regulation will be carried out. We can think that sectors such as mining and steel, for example, which certainly emit more than 10,000 tonnes of CO2 per year, will be regulated and will need to comply with specific decarbonization rules. Regulated sectors will need to submit emissions reports and decarbonization plans, among other things.

Source: IPCC

Some will need to offset their emissions by purchasing carbon credits. Sectors that emit much more than the limit defined by law will require a specific metric for annual emissions reduction. You need to define all these parameters, which is a complex task.

It is worth remembering that these sectors have the resources to meet these obligations, even if they need to acquire carbon credits to offset emissions. A good example is the oil and gas sector, which has the capital to invest in decarbonization. And companies will have time to prepare for this transition.

Will it take a while for the carbon market to be structured?

Yes. We can imagine a horizon of four to five years, according to the government’s own schedule. By then, companies will be better prepared to deal with the new decarbonization governance in Brazil.

First, the regulatory body needs to be established, which should take two years. It is also necessary to create sectoral chambers to discuss everything we are talking about. Afterwards, the intricacies of emissions monitoring and verification will have to be defined. It will be necessary to create a large database and a methodology so that the government can analyse emissions.

What are the main challenges of this process?

Emission limits must be defined by sector, with specific parameters for reducing emissions. There will be a gradual schedule, according to the characteristics and possibilities of each sector. All of this will be defined by the government together with representatives of the private sector, mainly industry, which is expected to be the sector most impacted by the new measures.

Sectoral meetings are already taking place to reach a consensus. The technical part, evaluating emissions, is also complex. We are talking about a huge database that will need to be built, as well as information analysis and verification systems.

Should the government also monitor carbon credit emissions?

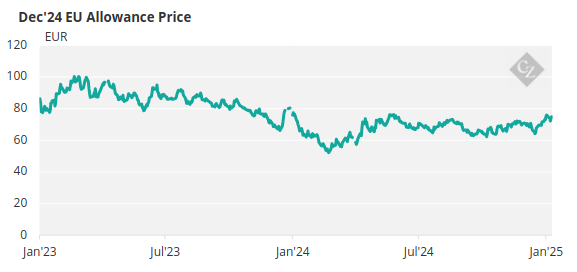

Yes. The idea is to monitor the volume of carbon credit emissions. There are a few reasons for this. One of them concerns market issues. It would not be beneficial to flood the market with carbon credits, which would cause the price of these bonds to fall. Ideally, they should be close to the values traded in already established markets, such as Europe.

The goal is also to encourage companies to reduce emissions and not just offset them by purchasing carbon credits. We are talking about a plan to encourage decarbonization and achieve goals set out in the Paris Agreement.

Source: ICE

In relation to business opportunities, which sectors should benefit most?

There is a great opportunity, for example, in relation to the recovery of degraded areas. There are around 100 million hectares of land that can be recovered and generate carbon credits. The bioinputs market is another candidate to generate credits, as is the renewable energy and biofuels sector. There are countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, that are already looking to Brazil to offset their carbon emissions.

Do these countries intend to buy carbon credits on the Stock Exchange, when this market is structured, or do they have decarbonization projects here in Brazil?

Some intend to generate carbon credit here to take advantage of opportunities in our domestic market, which is expected to grow a lot. Acelen Renováveis, an energy company created by the Mubadala Capital fund, from the UAE, is a good example.

The company has already announced investments of BRL 12 billion to produce green diesel and SAF in Bahia and the north of Minas. The interesting thing is that the project includes the recovery of 200,000 hectares of degraded areas, already considering the possibility of issuing carbon credits.

If Mercosur closes the free trade agreement with the UAE, which is being negotiated, there will probably be more initiatives like Acelen’s. Free trade agreements generally include investment facilitation clauses.

Have European countries and other regions of the world shown interest in Brazilian carbon assets?

Europe is interested in this, and we have Middle Eastern clients desperate for these assets. These are countries that need to offset their emissions, and Brazil is a natural candidate to be a large emitter of carbon credits due to our biodiversity and sustainability in the generation of energy, fuel and gas, for example.

The expansion of markets such as biofuels is very important for the issuance of carbon credits. Now, with the Future of the Fuel bill, our production should increase significantly. The possibilities are very interesting.