Insight Focus

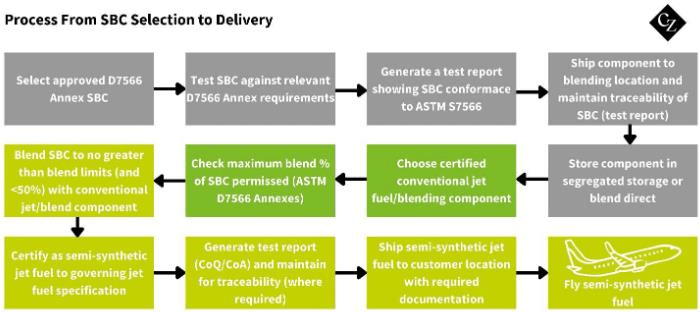

Blending SAF involves adding sustainable components (SBCs) to jet fuel. This process requires strict certification since SBCs are not jet fuels themselves. Unlike routine in-wing mixing, this is classified as manufacturing to ensure safety and compliance. These steps are essential to meet regulatory standards.

Blending SAF means integrating neat sustainable components into conventional jet fuel to create SAF. Is this difficult, and if so, why? And if not, why are we making such a fuss?

Challenges of Blending SBC

To the untrained eye, it might seem reasonable to note that if the sustainable blending component (SBC), produced from non-crude-oil feedstocks and new processing routes, is a hydrocarbon that falls within (or even close to) the range of properties of Jet A or Jet A-1, then why is blending so carefully controlled?

Can we not add the SBC and send the blend on its way – end of story? Surely, when an aircraft is refuelled, blending happens in the aircraft tank as its contents mix with the fresh fuel pumped on board. So, where’s the difference?

The difference is that SBC is not a jet fuel but a blending component. Its addition constitutes a process that, by definition, is part of the manufacture of a (new) jet fuel.

Ensuring SAF Blends Meet Standards

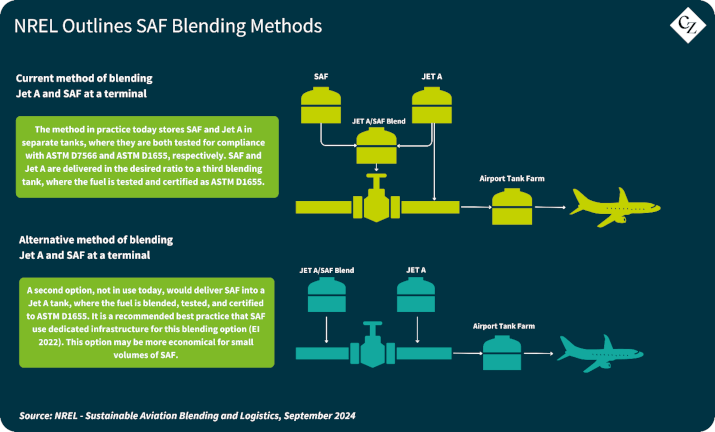

As a result, additional rules apply to ensure the blend meets specification requirements, including full laboratory certification of the blend. Adding a blending component, such as an SBC that doesn’t meet jet fuel specifications, is classified as a manufacturing process.

Therefore, as in a manufacturing centre like a conventional refinery, a full certification must be conducted on the resultant blend. The refinery performs this as part of the manufacturing process, and the blending site is required to do the same.

In-wing mixing of different jet fuels is not comparable—mixing two on-specification jet fuels occurs routinely in airport storage tanks and aircraft tanks without requiring further checks, apart from occasional, simple, and routine density and appearance checks.

The absolute requirement for full certification of a SAF blend isn’t an arcane, self-serving barrier devised by professorial types to hinder users, operators and customers from implementing SAF mandates, even though it might seem that way. It’s a new process that must still comply with the existing rules.

The full certification of jet fuel after the addition of an SBC is a critical step to ensure that aircraft are fuelled with on-specification, fit-for-purpose product. A collection of hydrocarbons only qualifies as jet fuel if it has been tested against, and meets, the requirements of a recognised jet fuel specification.

There are additional rules, which we’ll explore in future updates. For the brave, I suggest getting hold of a copy of the reference document EI1533 published by the Energy Institute. At over 80 pages, it highlights the complexity of the topic. Enthusiasts looking to complete the picture may also find ASTM D7566 worth a read.

As well as carrying out the full certification of a SAF blend jet fuel, a number of extra checks are required on blends, depending on the type of SBC. We’ll explore these in coming articles.