Insight Focus

SAF must be blended into CJF and certified. Blending is regulated, requiring extra checks that increase costs, time, and operational complexity. These checks ensure the final fuel meets all safety and performance specifications for aviation use.

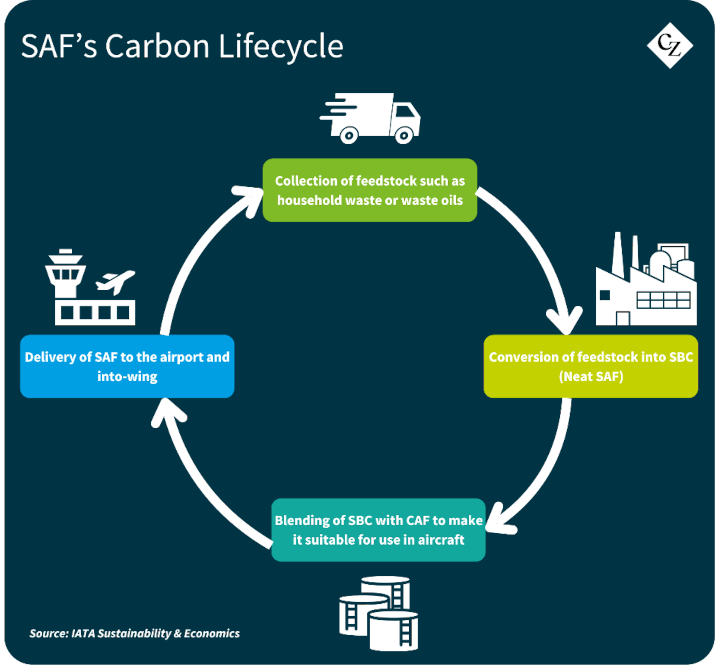

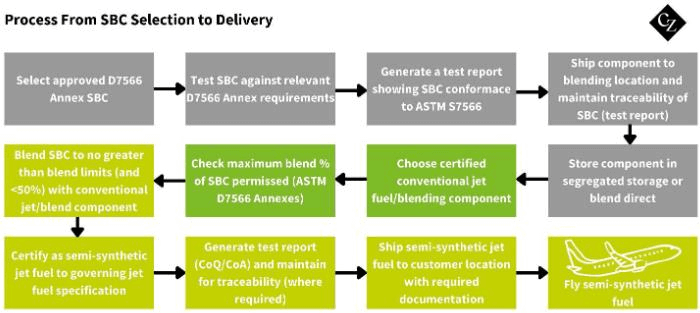

In our previous article, we explained that sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is made by blending a synthetic blending component (SBC) into conventional jet fuel (CJF) and then verifying that the blending is complete and that the SAF is fit for purpose through laboratory analysis of a blend sample.

The aviation fuel industry, built on sound principles of risk management, has permitted the inclusion of new feedstocks and processes that lead to jet fuel, but only with additional checks to mitigate the risks introduced by these changes. It is possible, though by no means certain, that once fuel experts have gained more experience with SAF, the blending rules will be relaxed.

In the meantime, the key rule is that the blending of an SBC must be verified through a full certification of the final blend, with its properties compared against the specification requirements. This certification is required each time an SBC is added.

Therefore, if SAF arrives at an airport with two different SBC components added (more than one is allowed, but only if certification is carried out after each SBC), the airport fuel service manager will have at least five certificates for the fuel: one for the CJF, one for each of the two SBCs, and one for each of the two SAF blends, along with any recertification documentation required along the distribution system.

A small number of additional checks are also required. These checks are specifically targeted at the risks associated with the particular properties of the type of SBC being blended (referring to the specific ‘Annex’ of ASTM D-7566).

Jet A/A-1 is a complex blend of hydrocarbons, both paraffinic and aromatic, along with a small quantity of non-hydrocarbons, such as sulphur, which enhances lubricity. SBC, on the other hand, is predominantly paraffinic and contains no sulphur. Therefore, when blending SAF, it is important to check the properties safeguarded by aromatics and incidentals like sulphur—such as density, boiling range, viscosity, and lubricity.

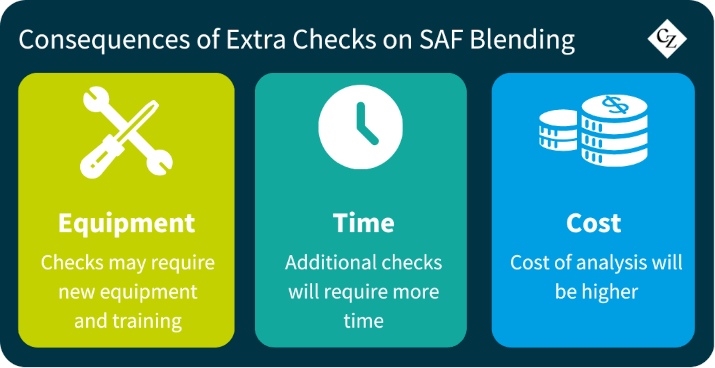

Extra Checks Increase Costs

The consequences of these extra checks of the SAF blend are moderate but require careful consideration by blenders. First, the laboratory responsible for recertification may not initially be equipped to perform the additional checks, potentially requiring extra equipment and training. Second, the extra checks may take more time to complete. Finally, the cost of analysis will be higher. These are all factors that must be considered when determining batch size and other operational details at the blend site.

Blending, then, isn’t particularly difficult, but it is comprehensively regulated. Unfortunately, the confirmation process is both cumbersome and expensive. Blending can occur at the refinery, terminal, or even adjacent to airport storage, but there are penalties in terms of time and cost associated with each blend event. These penalties may influence where a blend is managed.

The analysis costs to confirm blend efficiency help explain why many suppliers favour co-processing. Co-processed jet fuel does not require additional checks outside the refinery—providing a clear advantage in the race to get SAF more widely adopted.

In our next article, we’ll explore co-processing in more detail.