Insight Focus

Consumption habits are changing. While everyone acknowledges that we should be eating more fresh fruit and vegetables, producers and retailers are still struggling to communicate this message effectively to consumers. But if growers can use effective marketing techniques, they may even be able to overcome cost concerns among consumers.

Healthy Eating Under the Microscope

Around the globe, consumers put “eating more healthily” pretty much at the top of their “To Do” list for 2025 and it’s for good reason as, increasingly, the majority of the population are as round as puddings. Prestigious medical journal The Lancet forecasts that more than half of adults and one-third of children worldwide will be overweight or obese by 2050. Yet, eating healthier is easy to say and, clearly, difficult to do. Eating more fresh fruit & veg would be a good start. And that’s exactly what people aren’t doing! What’s the story?

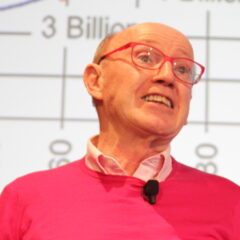

Take higher income countries, across the EU, UK, the US, New Zealand and Australia, longer term per capita fresh produce consumption has trended downwards – although market volumes may have increased driven by increases in population.

Source: FAO

Economic downturns are not a friend of the fresh produce industry, and the current “cost-of-living crisis” is a case in point. In regular times, fruit and vegetable consumption by lower income urban families is significantly less than in better off families. When the purse is pinched, this is simply accentuated.

Through the past few decades, cost per calorie of “value”, albeit unhealthy foods, such as some cookies, cream cakes and skimpily covered pizzas have become substantially lower than healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables (F&V) and they provide convenient, low-cost meal solutions and assuage hunger whereas salads, cabbage and apples don’t!

Most Western countries are far from achieving anywhere near their five-a-day F&V targets (exceptions being Greece, Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Poland) and there’s been a pervasive drift, across most continents, towards an American-style diet, i.e. one characterised by a high proportion of the controversially defined Ultra Processed Foods (UPF).

By the bye, females are more fresh produce friendly than males, particularly if they have small children (and the urban myth is that a Glaswegian male is more likely to be seen doing needlepoint than eating fresh fruit!).

The market is flooded with convenient solutions to fix a meal in no time. Photo credit: David Hughes

So, do we just need to lower prices to increase consumption of nutritious fresh F&V? No and, fresh produce growers, park your anger for the moment at the thought of doing such!

Berries Top of the Pack

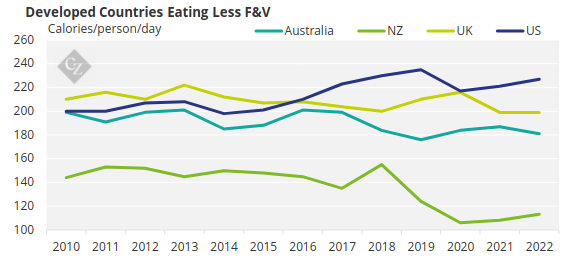

Here’s a mini case study on the UK fruit market. Keep in mind that this market is largely serviced by imports – 56% from outside Europe, 28% EU and a modest 16% home-produced. Over the past 15 years, per capita fresh fruit consumption has seen a tiny increase (3%) and is about 40kg/capita.

From 2010 to 2024:

- Total fresh fruit retail market value increased from GBP 4.1 billion to GBP 7.2 billion and volume from 2.47 million tonnes to 2.8 million tonnes while UK population increased from 62.8 million to 69.1 million;

- In volume terms, bananas continue to be the UK’s favourite fruit, followed by apples, and citrus but all three have slipped in the consumer’s affection. During this time, the composite category berries have close to doubled their share, tropical fruit have advanced significantly and grapes have edged forward. Pear volume share of the market has nigh on halved;

The UK is an intensely price competitive market with supermarket own label products dominating. The two principal hard discounters – Aldi and Lidl – have had huge success in expanding fruit value market share from 6% to 22% at the expense of traditional supermarkets and the dwindling independent trade, ensuring inexorable downward pressure on retail F&V prices.

Photo credit: David Hughes

Low although prices may be, there’s positive news for the UK fruit industry in that retail fresh fruit market volumes peaked in 2020 and 2021, then declined in 2022 but recovered in 2024 to close at the previous peak levels.

So, is price driving consumers’ choice of fruit category? Perhaps surprisingly, NO! Fresh berries have a retail price point per kilogram some four times that of apples and pears, and eight times of bananas. Yet from 2010 to 2024, fresh berries have increased their value share of the retail fruit bowl from 17% to 29% of total and look on course to taking a full one-third of retail fresh fruit sales by decade end (with blueberries leading the charge).

Source: gov.uk

Bananas, at GBP 0.99/kg, are essentially a “free good” and have seen less than a 10% increase in retail price over the 15-year period, whereas average retail apples prices rose 47% from GBP 1.45/kg to GBP 2.13/kg and berries by 48% from GBP 5.71/kg to GBP 8.47/kg.

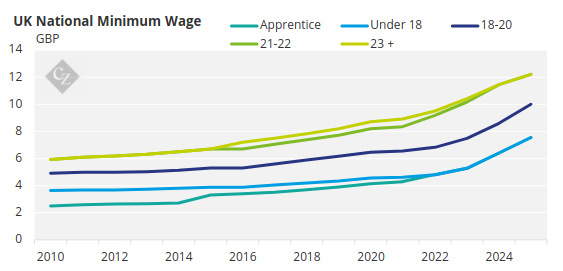

Do such increases compensate fruit growers for input cost increases? Far from it. For berries, labour costs account for around 50% of total costs and minimum wages have doubled from 2010 to 2025.

Source: gov.uk

Of course, consumers have other choices than just fresh F&V. In the UK, the Covid period saw a boost in frozen purchases driven by perceived convenience, less waste, cost competitiveness and an improvement in consumers’ perception of the nutritional quality of frozen produce.

Chilled ready mashed potatoes are now becoming a routine purchase for many households and, looking to the future, frozen chopped onions and garlic look likely candidates for sales growth. Constraints to the expansion of frozen include availability of freezer space in the home, and concerns about “additives” in frozen products.

Pineapple aroma and a hint of vanilla… it’s not your wine; it’s a pale strawberry! Photo credit: David Hughes

There are several major factors underpinning the success of relatively pricey fresh berries in so many markets including:

- their perception as a treat (and even in stringent economic times, who doesn’t need a treat?)

- they are loved by children

- crucially, they’re convenient (you don’t have to peel them!) and intrinsically snackable;

- they are seen as health heroes, particularly blueberries;

- they’re widely available year-around which encourages weekly “routine purchases”;

- berry brands have embraced the good-better-best* tiers;

- and, like some other fruits, accelerated investment in R&D has delivered notable improvements in the qualities appreciated by customers.

Zespri’s Kiwi Gold and RubyRed kiwis are good examples of combining the power of intellectual property and branding to “decommodify” the more generic green kiwifruit category. All produce items need to avoid “the commodity trap” epitomised by bananas – with 99% of those internationally traded being the Cavendish variety.

Photo credit: David Hughes

Famous brands are associated with the fruit – Dole, Chiquita, Del Monte, Bonita, Fyffes and more – but few, if any of these generate a significant brand premium. For instance, would you switch supermarket because they’re out of Dole bananas rather than your regular Chiquita ones? Bananas have the dual function for the supplier of delivering huge volume in shipping such that they can inexpensively add on other higher margin produce.

Smoothies, Juices Shoulder Marketing Efforts

Returning to the healthiness of fruit and vegetables, where can customers garner compelling claims as to the benefits of fruit and veggies (and it’s not in the fresh F&V aisles of the supermarket)? Wander around pharmacies such as Boots and note that cucumbers and berry extracts are lauded for their skin beautification properties.

In the premium juice and smoothie aisles of supermarkets, product labels are crammed with claims relating to F&V portion equivalents that can be ingested with a few glugs in seconds! In any major supermarket, there are hundreds of fruit and vegetable drinks, juices and smoothies on offer.

For instance, happy monkey smoothies boast on front of packs that they are “made for kids with 100% fruit. No bits (God forbid!), no additives or added sugar, one full portion of fruit, great for lunch boxes”.

Can these drinks be considered fresh F&V competitors? Sure, why bother buying the real thing? In the fresh produce industry, we’ve largely relied on others to make motherhood claims about our F&V. But claims that they are “a good source of vitamins and minerals” are insufficiently visceral, they don’t connect.

At a time when consumers say they want to eat more healthily, they seek specific credible information on what the benefits are to me and my family (and, more challengingly — how long before I can see the benefit?).

Joyvio, the leading fresh blueberry brand in China, hits this nail on the head – its claim that blueberries improve/are essential for eye health is widely embraced by consumers.

Small Growers Get Creative

Across the globe in the fresh produce industry, rapid change is afoot. Commercial horticulture is simply increasing in scale. The investment cost to be at the leading edge of F&V production is accelerating through this decade and will continue to do so.

The mid-20th century saw the global “Green Revolution” fuelled, in part, by significant public sector funding but now, the “HortiTech Revolution” is dominantly private sector funded and there’s a substantial entry cost for those horticultural businesses wishing to be on board. You want to reduce in-field labour costs and cut out herbicides? The smaller “LaserWeeder” costs you USD 600,000 and its big brother USD 1.5 million.

Harvesting robotics are still at an early stage but will be with us at decade end as will profitable, albeit eye-wateringly expensive, advanced vertical farming. Horticultural crop breeding is being transformed by a combination of AI and gene editing (e.g. look at what Heritable Agriculture and AddGene have to offer).

There’s now increasing polarisation in horticultural businesses. For example: fashionable, high growth berry and avocado sectors are seeing massive consolidation (note the acquisition journeys of Driscoll’s and Westfalia Fruit).

In Australia, 10 horticultural businesses, some infused with private equity investments, account for over 50% of F&V sales. Branded bag salad giant Taylor Farms in the US is investing in the European salad sector. In varietal development and licensing, Sun World International for fruit and Sakata for vegetables are expanding. And of course, in frozen potato products, McCain’s, Simplot, Lamb Weston and Aviko sit astride the rapidly expanding world of frozen French fries.

If the Big-League horticultural players have economies of scale, financial capacity to harness technological innovation, ownership of/exclusive access to valuable varietal intellectual property (IP), a consumer relevant brand and a suite of major supermarket customers, where does this leave smaller-scale fruit & vegetable businesses?

In short, they’re scrambling! Food producers across the world are grumpy but horticultural growers are a step above grumpy and into incandescent rage territory. For example, one-third of Australian vegetable growers are considering exiting the industry. It’ll be a similar figure for UK fruit growers who have only a small proportion share in their home market. Can growers strengthen their position? Options can include aligning their own businesses with those with IP and brands.

For example, the New Zealand Government-owned Institute for Plant & Food Research is adept at developing partnerships. Notably, it has worked with grower-owned Zespri, the number one global kiwi fruit exporter, and with venture capital-owned Rockit, exporting “mini-apples in a tube” to over 20 countries.

California-based Sun World was a pioneer in the fruit industry, working with select growers and marketers worldwide in introducing new varieties of grapes and stone fruit.

Japanese seed company Sakata partners with marketing organisations in Europe (Bimi/Tenderstem), the US (Baby Broccoli) and Australia (Broccolini) who work with local growers to produce a popular green vegetable that is a cross between Chinese Kale and broccoli. It also sells at a substantial price premium to commodity broccoli.

Apple & Pear Industry Australia uses a similar approach to Sakata in marketing Pink Lady apples around the globe. Pink Lady are grown in Australia, New Zealand, Europe (but not yet in the UK), South America and South Africa and achieve a mouth-watering price premium in Europe and beyond.

G’s Fresh in the UK works with growers and cooperatives in the UK, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain and Senegal to supply salad crops and vegetables to major retailers in the UK.

Photo credit: David Hughes

Should small-scale horticultural businesses consider using their scarce resources in other ways? Well, smaller scale can work in servicing very local markets with strong customer connections, and/or wider markets with more niche, specialty fresh and processed products.

In the UK, the tiny Isle of Wight provides examples – Isle of Wight Tomatoes sells fresh tomatoes and tomato condiments, and The Garlic Farm markets fresh garlic, plus a host of processed garlic products and tourism.

I have my own personal experience as co-owner of a small hydroponic herb farm in Florida, which developed a range of branded packaged fresh products selling consistently at a premium to the commodity herb market. But, whilst Ernst Schumacher advised us that small is beautiful, in a mid-21st century commercial horticultural context, small is also fragile and may need support from other income streams!