Insight Focus

- Brazilian soy planting starts in September, but it only picks up in October – and that’s normal.

- There are big differences among producing regions, including how La Niña impacts yields.

- Brazil’s soy area has grown 66% in the last ten years, and most of the increase hasn’t been in the Amazon.

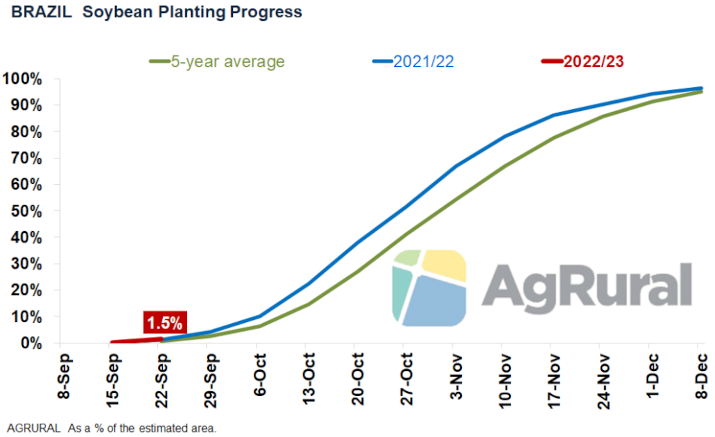

The record area of 42.7m hectares that Brazil will cultivate with soybeans in the 2022-23 crop was 1.5% planted by Sep 23, in line with the 1.3% sown in the same period last year and ahead of the 0.8% of the five-year average, according to AgRural data. In Brazil’s number-three producer Paraná, planting was 8% complete, while in Mato Grosso, the country’s largest soybean grower, the area already planted hadn’t reached 2% yet.

As rains are still irregular in Mato Grosso, most farmers prefer to wait for a little more moisture to boost the planting pace. This doesn’t mean, in any way, that there’s already a delay, as some are tempted to speculate every year that planting takes a little time to take off in the second half of September. Therefore, and considering other recurring questions from people who would like to know Brazilian soybean production better, I have gathered here five tips to help understand what is important to have in mind during the crop season.

1. Slow Planting Progress in September Is Normal and Doesn’t Weigh on Yields

The first states authorized to plant soybeans at the beginning of each Brazilian crop are Paraná (Sep 10); Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo (Sep 15); Minas Gerais (Sep 24) and Goiás (Sep 30). Before those dates, planting is prohibited in order to control the spread of the Asian soybean rust. This doesn’t mean, however, that all farmers start planting in full swing as soon as sowing is allowed.

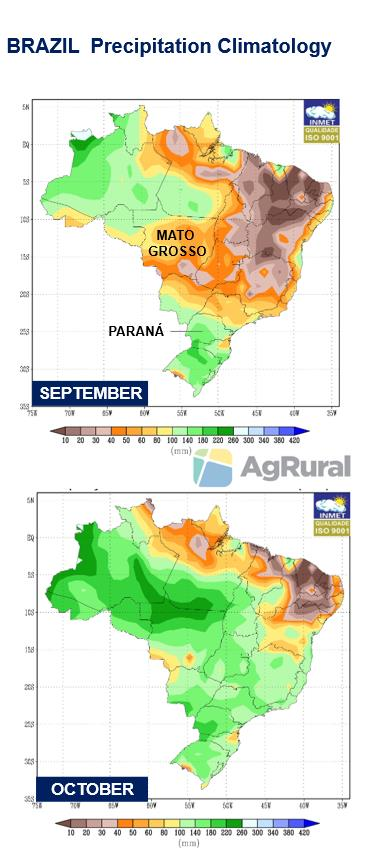

In Paraná, where rains are normally more abundant in August and September, the soybean planting tends to start as soon as allowed and it progresses relatively quickly, as soil moisture is already at acceptable levels. In Mato Grosso, on the other hand, the very dry and hot winter makes planting dependent on the first rains of spring – which start in the second half of September, but become more regular only in October.

Starting to plant only in October doesn’t mean delay or loss of yield potential for soybeans. The optimal planting window, by the way, starts in October. When the weather conditions are favourable, producers already plant in the second half of September just to have a more comfortable window for sowing the second crop. Cotton and corn are planted in January and February, right after the soybean harvest, and the earlier this happens, the greater the chance of those two crops having good yields. Therefore, when soy planting takes a little longer to get in gear, it is the second crop that suffers, not the soybean crop.

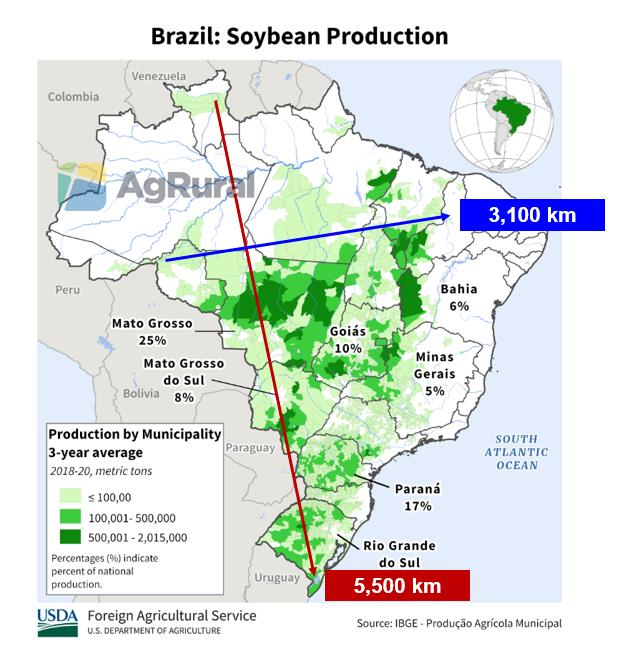

2. Brazil Is a Huge Country and There Are Big Regional Differences

Unlike the USA, where about 85% of the soybean production is concentrated in the Midwest, in Brazil there is not exactly a “soybean belt”. The planted area extends from the extreme north of the country, in Roraima, to the extreme south, in Rio Grande do Sul, and from the extreme west, in Rondônia, to Piauí, in the Northeast. That results in big differences in terms of crop calendar, climate and soil. In the south of Rio Grande do Sul, for example, soybeans have advanced over rice areas and can be irrigated, as the region usually has hot and dry periods during the pod-filling stage, in January and February. In Roraima, farmers plant their crop in April, May and June, when other states have already finished harvesting.

3. The Soybean Area Major Increases Are Not in the Amazon

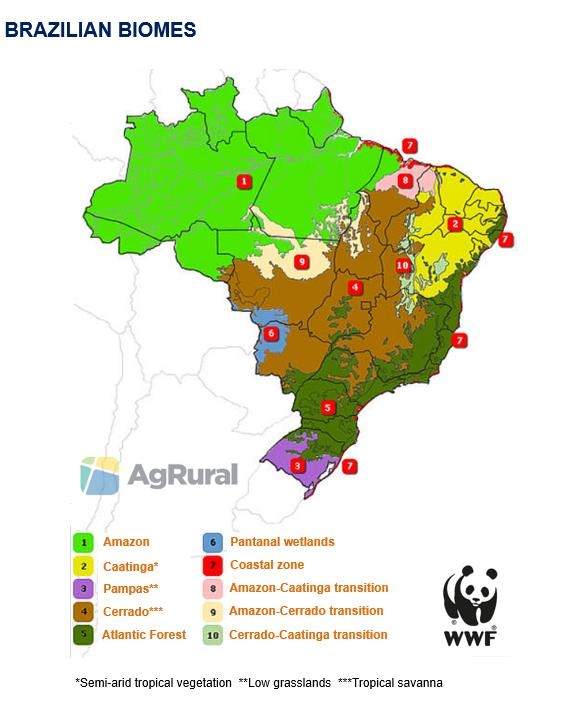

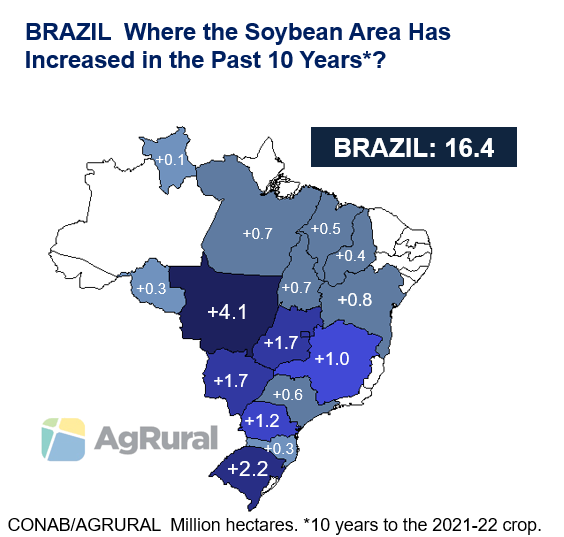

Brazil’s soybean area jumped by 16.4m hectares, or 66%, over the past ten years. For those who are unfamiliar with Brazilian agriculture, this data may bring to their minds many sensationalist headlines that trumpet soybeans as the great villain of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. That is not true. In absolute numbers, the state where the soybean area grew the most during the period was Mato Grosso, with 4.1m hectares.

Mato Grosso is within the so-called “Amazon Biome”, but most of the state is covered by savanna vegetation (“Cerrado Biome”). In this case, producers are allowed to legally deforest 35% of the property’s area for planting. Most of the advance in recent years, however, has taken place over degraded pasture areas rather than newly cleared areas.

The second state where the soybean area increased the most (2.2m hectares in ten years) is Rio Grande do Sul, which is 2,600 kilometres from the “Amazon Biome”. Next and tied are Goiás and Mato Grosso do Sul, in the “Cerrado Biome”, with 1.7m hectares each. In the North/Northeast region known as “Matopiba” (Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia) and in Pará, states that are Brazil’s new agricultural frontier, the percentage growth was large in the last ten years (116%), but not that high in absolute numbers: considering the five states combined, the soybean area increased by 3.1m hectares.

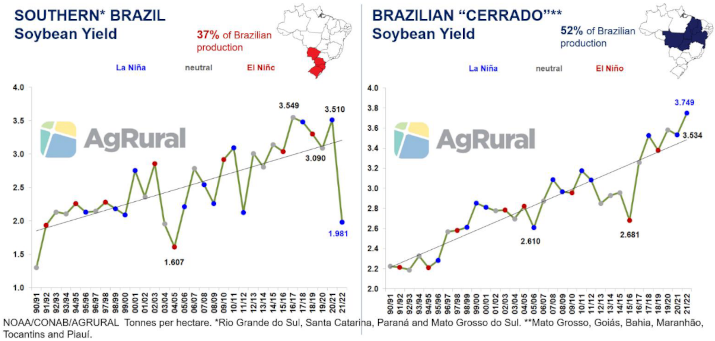

4. La Niña Impacts the South and Doesn’t Necessarily Result in Crop Failure

After experiencing a historic crop failure in the 2021-22 season (drought-related losses exceeded 20m tonnes), Brazil is starting to plant the 2022-23 crop under the threat of a third consecutive La Niña. The phenomenon usually makes more serious hot and dry periods that normally occur in the southern portion of South America between December and February, when soybeans are in reproductive stages and defining yields.

That was the case in the 2021-22 season, when yields had a sharp drop in Brazil’s three southern states (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná) and in the southern part of Mato Grosso do Sul (a state located in the Center-West region, but with many climate similarities with its southern neighbours).

La Niña, however, is not an unmistakable cause of crop failure, as it doesn’t act alone in determining the volume of rainfall in southern South America. So much so that there have been La Niña years when yields were very good. In addition, La Niña doesn’t usually reduce productivity in other soybean growing regions in Brazil.

5. Too Much Rain in Mato Grosso Is Normal – Also During Harvest

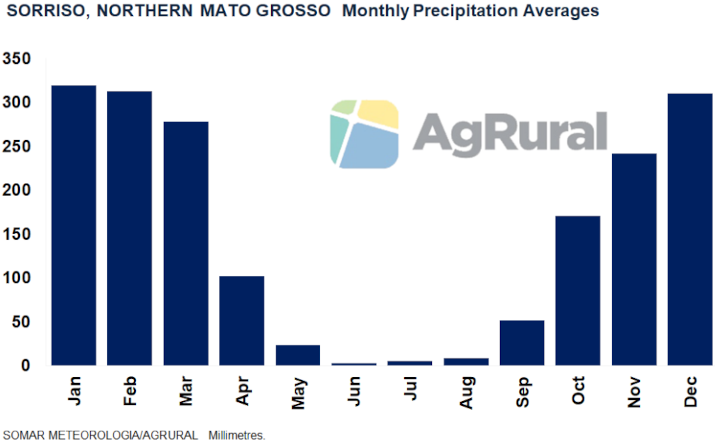

In Mato Grosso, the year has basically two seasons: the dry season (April to September) and the wet season (October to March). In Sorriso, northern Mato Grosso, for example, the average annual rainfall reaches 1829 mm. Of this total, 1633 mm (89%) fall between October and March. That’s why it’s necessary to be careful when evaluating precipitation anomaly maps for the state.

There are years, for example, when rains in December, during the pod-filling stage, don’t reach the 310 mm considered normal for the month, and that is shown on anomaly maps as “below average”. That doesn’t mean, however, that the rains were insufficient to guarantee excellent conditions for the soybean crop. Therefore, when it comes to Brazil in general and central states such as Mato Grosso in particular, always give preference to accumulated rainfall maps in your analyses, leaving the deviation maps in the background.

In addition, it is normal to rain a lot in January, when the soybean harvest begins in Mato Grosso. The climatological average of the month for Sorriso region is 319 mm. Therefore, grain quality problems, harvest delays and logistical challenges to take the new crop to the export ports happen very often. Those kind of issues are good for headlines, but they are normal problems that farmers and other links in the production and export chain know how to manage.