Insight Focus

High concentration within vegetable and seed oil markets has created a hugely volatile situation for prices. Lately, the price of palm oil has fluctuated greatly. But what are some of the main influencing factors that will dictate pricing?

Palm Oil Price Fluctuates

The palm oil price is extremely volatile. There have been several ups and downs in the past year or so – so why are the prices so temperamental?

Source: Investing.com

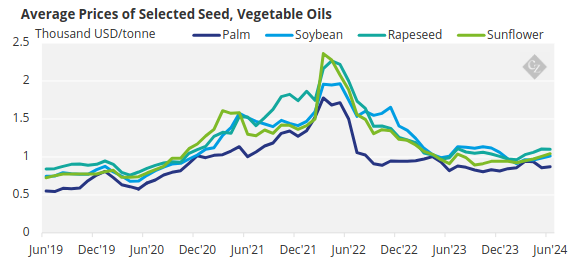

Well, the first thing to know is that seed and vegetable oils tend to be used interchangeably – sunflower oil can be replaced by canola oil for instance – and so prices tend to move in unison.

Source: World Bank

There are many factors that influence the price of palm oil – not least because the production of vegetable and seed oils is highly concentrated. This means that a significant event in producing countries can send the whole market moving up or down.

Source: Investing.com

We have identified six factors that have impacted palm oil prices in the past, continue to influence them or will have an impact in the future.

1. Protectionism

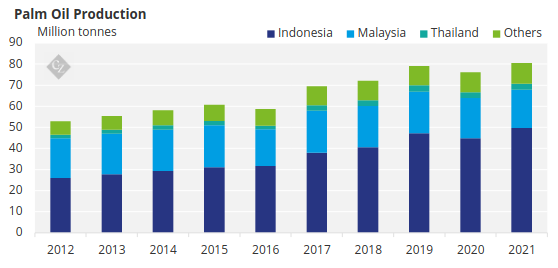

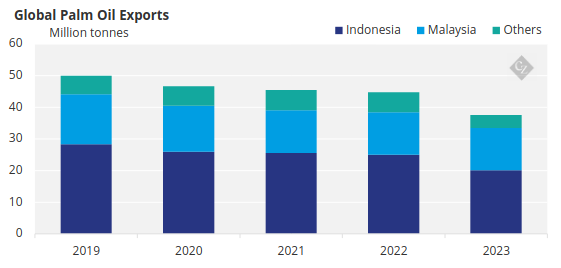

As we discussed, the majority of palm oil production is highly concentrated. In fact, Indonesia’s market share has increased continuously, and it went from producing just under 50% of the world’s palm oil in 2012 to over 60% in 2021.

Malaysia is also a major producer, with about a quarter of global production. That means that any protectionist moves in either of these countries has an immediate impact on prices.

Source: FAO

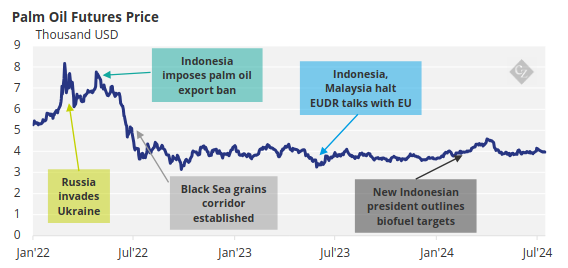

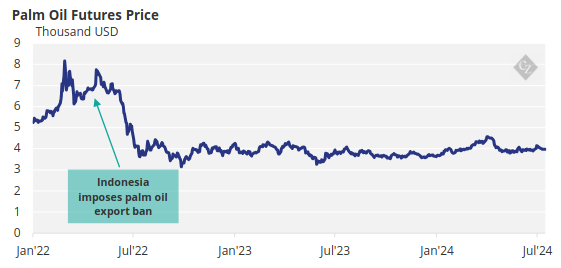

This was clear in April 2022, when the Indonesian government announced an export ban on palm oil. This led to the biggest price spike since the Russian invasion of Ukraine a few months earlier.

The ban was short lived, with the President lifting the ban as of May 23, 2022. Since, prices have normalised, but this demonstrates the importance of Indonesian and Malaysian foreign policy on the price of palm oil.

2. Structural Issues

As the world’s largest palm oil supplier, it is vital that production in Indonesia is sustainable.

Source: UN Comtrade

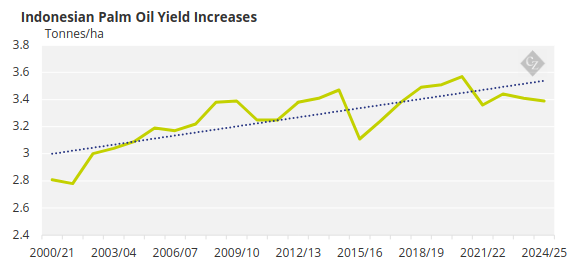

Over the years, palm oil yields in Indonesia have increasing, although there is volatility, and yields have tailed off in recent years.

Source: USDA

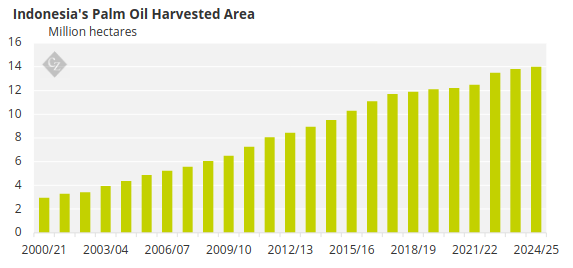

And rather than this being a result of greater productivity, it can be partially explained by an increase in the cultivated area. This has been increasing each year, albeit at a slower rate than it did through the early 2000s.

Source: USDA

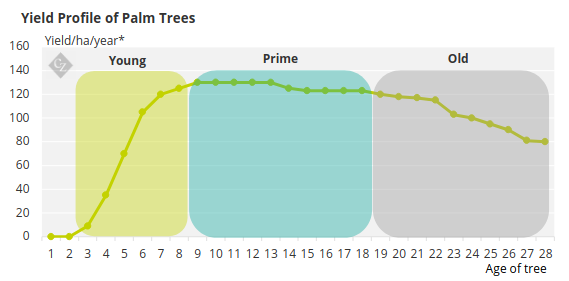

There is also a delicate balance between newly planted and mature trees. Palm oil trees tend not to produce until years 3-4 and reach peak maturity by year 10. By around year 18, the trees are considered to be in decline.

*measured as percentage of average yield over 28 years

Source: USDA

Late last year, the Malaysian Palm Oil Association released an estimate that showed that trees in about 12% of total planted area were over 25 years old. And over 33% of the planted area may fall into the declining category by 2027. If trees are becoming less productive, this could lead to lower global palm oil supply, which may only be offset by increasing planted area.

There are now dedicated efforts to prevent any expansion of palm oil planted area. Indonesian authorities have begun to crack down on illegal palm oil cultivation and the Palm Oil Overlapping Food Crops program has begun to boost long-term production using crop rotation.

In Sabah, Malaysia, the government has pledged to increase coverage of protected areas by 30% and certify all palm oil by 2025.

3. War in Ukraine

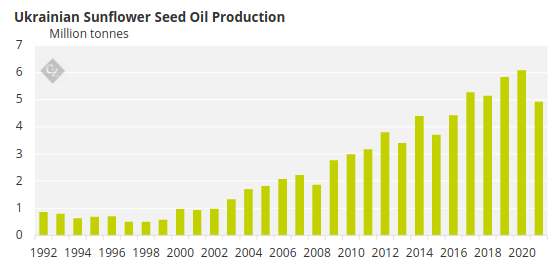

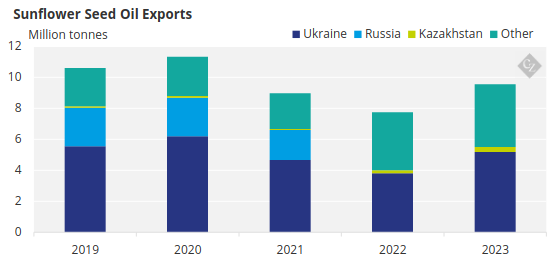

As we discussed, palm oil prices are not only impacted by palm oil supply – they are also influenced by the supply and demand dynamics of other seed and sunflower oils. This was apparent when Russia invaded Ukraine – the world’s largest sunflower seed oil producer and exporter.

Source: FAO

Ukraine accounts for about half of global sunflower oil exports and prices soared after the invasion. Likewise, after the Black Sea Grains Corridor was established allowing Ukraine to export food commodities again, prices began to normalise.

Source: UN Comtrade

This situation demonstrated the impact of the dynamics within other seed and vegetable oil markets on palm oil prices.

3. Argentina

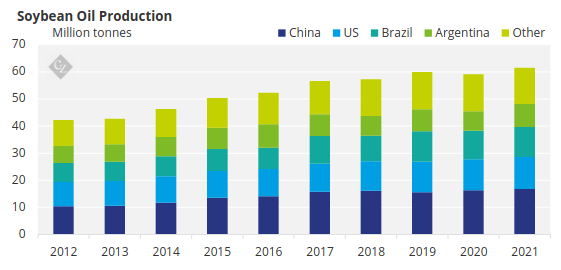

Another product that closely tracks the price of palm oil is soybean oil. Like sunflower oil and palm oil, production of soybean oil is highly concentrated. China is the largest producer, but three countries in the Americas are responsible for about 50% of global production.

Source: FAO

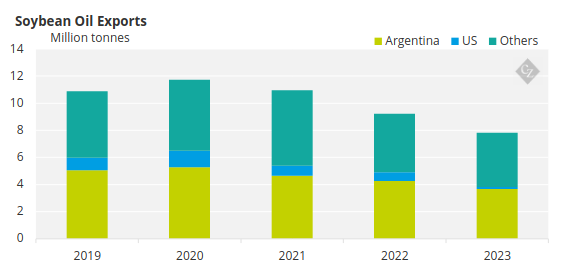

And while China, the US and Brazil tend to consume most of their soybean oil internally (mainly to produce biodiesel), Argentina is a major global exporter, accounting for just under half of international exports.

Source: UN Comtrade

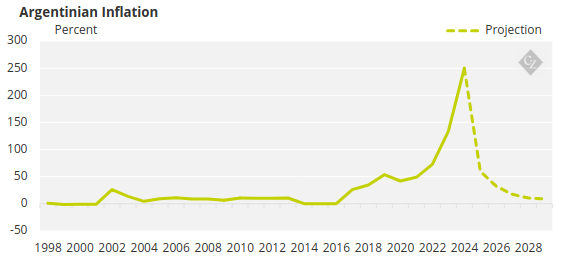

Recently, Argentina’s agricultural sector has taken a major hit. The country has been plagued by a historic drought for the past few years and is experiencing crippling inflation.

Source: IMF

The weather in Argentina has been extreme for at least two consecutive years, with eight heat waves recorded in the 2022/23 soybean season. If this marks a longer-term trend, soybean oil production could be greatly compromised, and availability could be limited. Argentina’s economic issues also limit the measures that can be taken to address the situation.

4. Government Fuel Policy

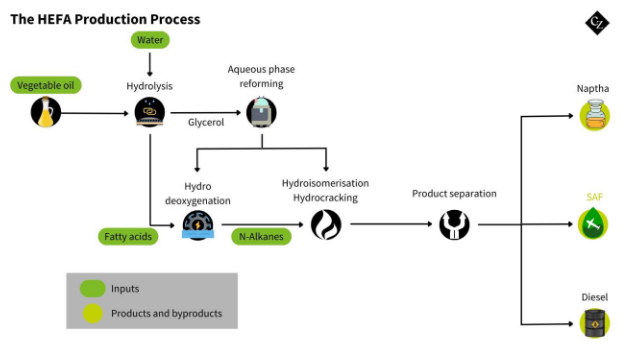

Edible oils can be used as a feedstock for biodiesel and for sustainable aviation fuel. As the world moves towards a more sustainable fuel source for travel, edible oils – including palm oil – will be in higher demand, pushing prices up.

Already, in Indonesia, the president-elect Prabowo Subianto has rolled out an ambitious renewable energy development plan. The plan increases mandatory biofuel content in diesel blends to 50% from the current 35%. He also plans to introduce bioethanol (E10) by 2029.

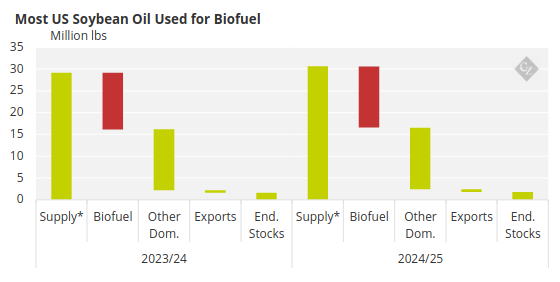

In the US, about half of all soybean oil produced is routed towards biofuels and about 70% of Brazil’s biodiesel is made from soybeans.

*includes beginning stocks, production and imports

Source: USDA

The Brazilian government also increased the mandatory biodiesel blend to 14% from 12% as of March 2024, reducing soybean oil availability on the global market.

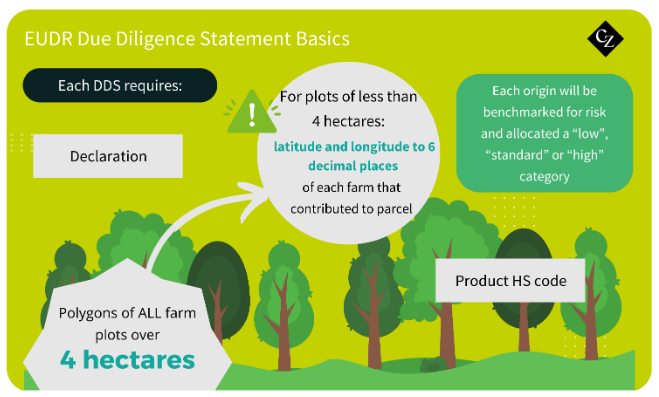

6. EUDR

EUDR will pose a huge challenge for European importers and exporters. The new regulations, coming into force at the end of 2024, impose stricter reporting standards across certain products, including wood, palm oil, soy, coffee, cocoa, rubber and cattle. Other products are expected to be included at a later date.

You can find all the details about what EUDR means HERE but in short, there are extremely strict requirements to ensure that these products sold into the EU are sourced sustainably and ethically. The EU now wants evidence that the products do not come from land linked to deforestation or degragation.

This poses a huge challenge for industries such as palm oil, which are composed of smaller landowners who may not be equipped to adhere to the huge amount of paperwork required.

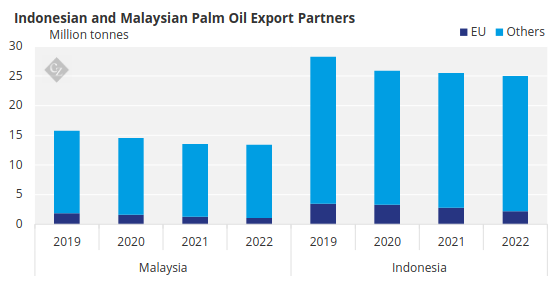

As a result, many of these sellers face being locked out of the EU market. The EU market represents about 10% of palm oil sales for both Malaysia and Indonesia.

Source: UN Comtrade

Both Malaysia and Indonesia filed complaints to the WTO, claiming that the ban is discriminatory. However, the trade body upheld the EU’s argument. Malaysia has since agreed a trade deal with China to double palm oil exports.

Not only is this measure likely to distort prices – particularly for palm oil entering Europe – but it could significantly alter trade flows.