Insight Focus

- Brazil’s enormous crop will test processing and logistics industries.

- Argentina may continue to import Brazilian soybeans for processing.

- China, the world’s largest soy importer, is increasingly dependent on Brazil for supplies.

2023 is turning out to be a momentous year for the South American soybean industry. Events taking place today likely set the stage for a very different soybean future, maybe quite different even from recent history. Years from now we may look back at 2023 and say something akin to, “that’s when it all started.”

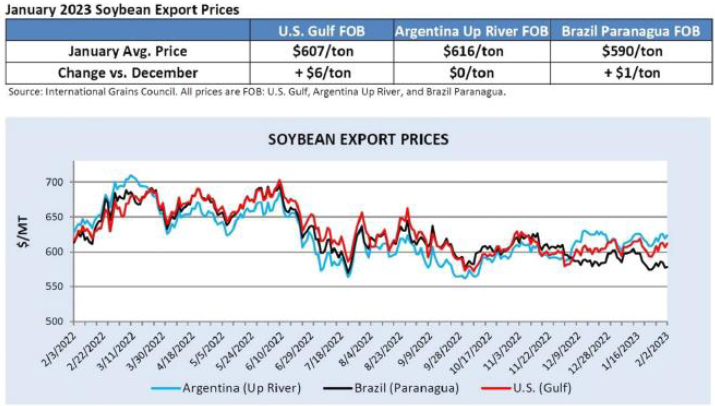

1) The Brazilian soybean farmer has produced a crop so large that the processing, grain warehousing, and logistics industries will struggle to absorb it. Brazilian traders will necessarily drive soybean prices lower to incent significant new demand and allow Brazil to dominate global exports. Chinese importers will be the primary beneficiary of Brazilian farmers’ productivity far outstripping commercial industry’s ability to efficiently handle the crop. Expect that black line in the chart below to stay well under the red and blue (celeste?) lines for quite some time.

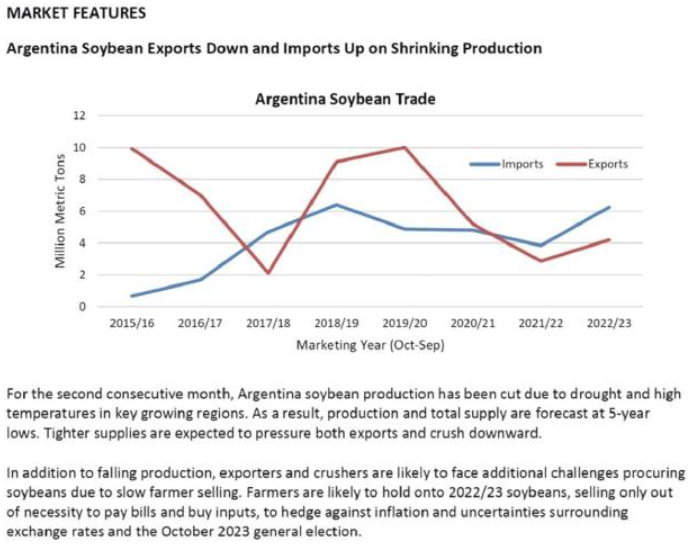

2) Argentina has lost nearly 14 million metric tons (MMT) of soybean production from peak estimates BUT may have found a solution (permanent?) to operate its extensive processing capacity with cheap Brazilian imported soybeans. Argentina’s crop losses in both soybeans and corn necessarily imply significant idled storage and processing capacity that may provide a ready solution to the Brazilian trader looking for markets where he can dump (sell aggressively and purposefully) soybeans.

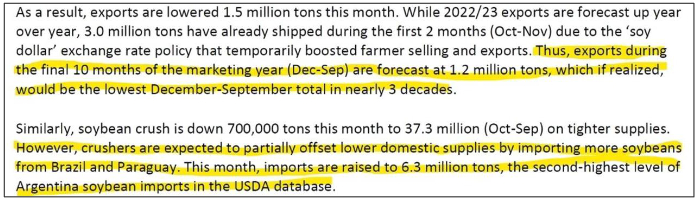

The USDA featured the Argentine crop losses in its opening to its February edition of Oilseeds World Markets and Trade and touched on the ongoing reluctance of Argentine farmers to exchange their dollar priced last year’s soybeans for pesos (and the Argentine farmers are up 2-nil in their currency exchange tournament with the Argentine government this year with indications of a 3rd match coming up [the so called peso-dollar 3.0] and I am taking the over on the farmers).

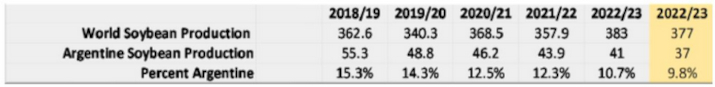

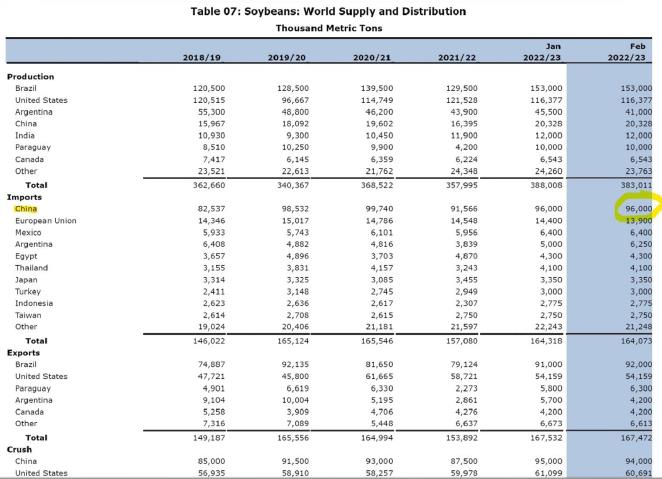

Over the last 5 year’s Argentina’s soybean production has sequentially spiraled lower (see table below with values in million metric tons [MMT] and sourced from the USDA; orangish (marigold?) box represents a Cronin projection of subsequent USDA reports decreasing Brazilian production by 2 MMT and lowering Argentine production by 4 MMT; all subsequent grey boxes use USDA’s most recent data).

Argentina’s percentage of global soybean crushing continues to spiral lower:

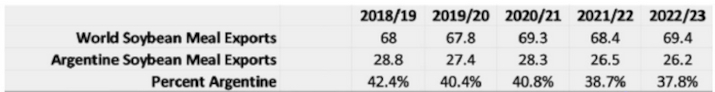

Argentina’s participation in global soybean meal trade continues to spiral lower:

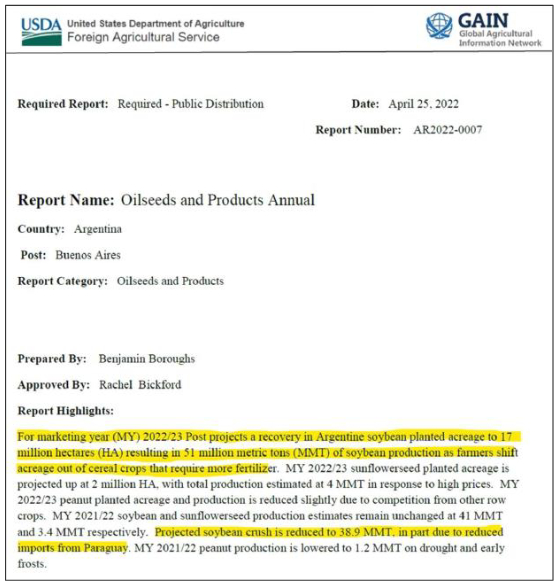

Here was the optimistic view of the USDA’s boots on the ground (Buenos Aires) last year when he made his initial forecast for this year’s crop:

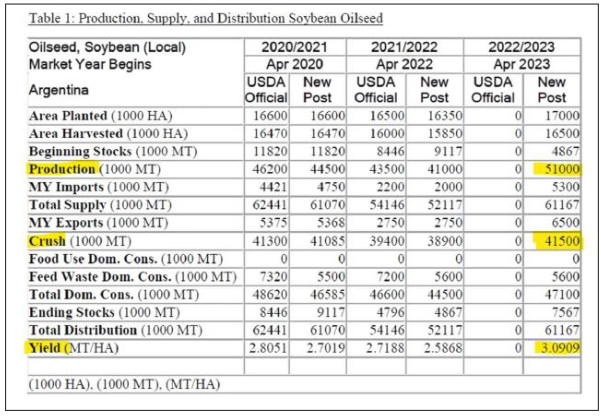

And these were his optimistic crush and crop yield (metric ton per hectare) forecasts:

As the USDA data tables above show the Argentine soybean Production number now comes in at 41 (37 for Cronin and taking the unders on that all the way down to 33 35) versus the original forecast of 51 (above), Crush in the USDA data tables now 37.3 versus 41.5 originally (above) and Yield likely well below the year ago’s 2.58 tons per hectare. All in all a complete crop disaster for Argentina.

The bright spot for Argentine’s crushing industry is soybean imports likely stabilize (instead of collapsing further; see below table) and potentially bring a new dynamic in the soybean relationship with Brazil, whom I referred to as the Saudi Arabia of soybeans in this essay https://tinyurl.com/ujvu3yfk. Should Brazil continue to produce enormous soybean crops like this year’s and continue to lack the processing, storage, and logistic capacity to avoid dumping soybeans on the world markets (a good bet unless the Chinese invest more in infrastructure), Argentine processing capacity benefits.

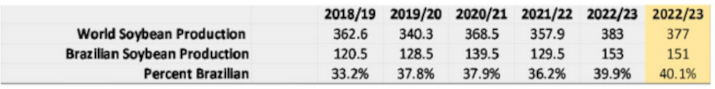

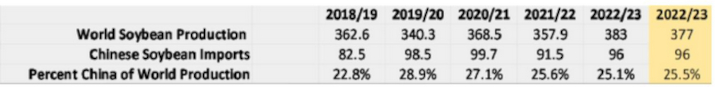

Brazilian soybean production dominance continues to unfold with a fairly obvious path for 50% of the world’s soybean production to originate from Brazil in the coming years (as the table below shows the astounding move from 30% ish to 40% unfold over a brief five years):

USDA highlighted this year’s “Brazil gives, Argentina takes” development this way: Argentina exits the global soybean export business with the slowest December-September export pace in 30 years and imports Brazilian and Paraguayan soybeans at a near record pace since USDA records have been kept:

Conclusion: The new relationship between Brazil and Argentina potentially brings Argentine crushing capacity a second life should the two agricultural rivals find a way to peacefully collaborate and potentially contributes to other common initiatives:

The primary beneficiary from Brazilian soybean largesse is China, top of the league tables for global imports (actually, as the table below displays, China is an import league all by itself):

China consistently imports 25% of the world’s production even as it steps higher year in, year out due primarily to Brazilian productivity. Consistently needing 25% of growing American (Brazilian, US, and to a lesser extent Argentine) production is a Chinese strategic weakness (more below):

So what are the other conclusions to be made about this momentous year for Latin American soybean production and what will we say about this year when we look back on it from five years hence:

- China’s dependency on Brazil for soybeans stepped up significantly and likely leads to some form of soybean diplomacy between the two countries; 96 million metric tons of imported dependence is likely not lost on the Chinese leadership

- Argentina’s dependency on Brazil for soybeans stepped up significantly and the Argentine government now has some real leverage on its farmers who hoard production to get favorable dollar/peso exchange rates

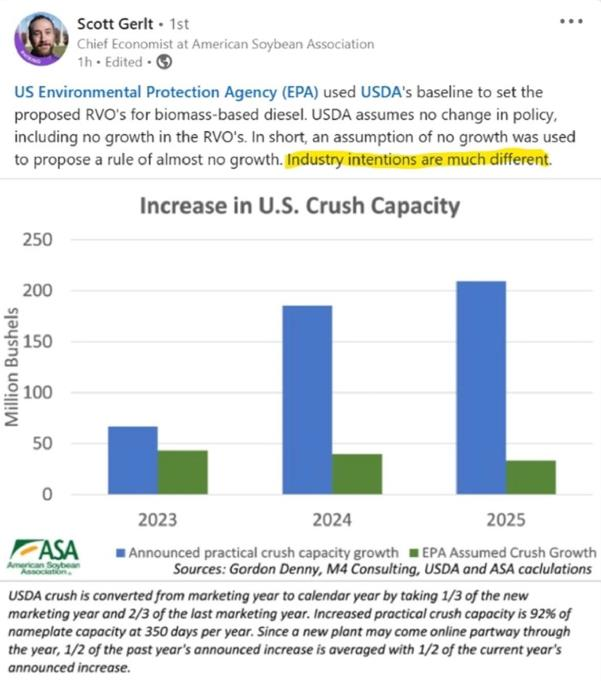

- Brazilian traders will need to find more destinations that can accept very cheap soybeans due to Brazilian production far outstripping Brazilian commercial capacity to meter out production judiciously (could there be a location in the world that is expanding its need for soybeans by 30% and might be able to help Brazilian farmers with a tremendous nearby uplift in demand)?

China’s increasing disadvantage due to its soybean import dependency is a great weakness and leaves the country exposed to a domestic food supply implosion should the US and Brazil jointly embargo soybean exports to China over some event, like say an invasion of Taiwan.

Over the next 3 to 5 years, US growth in domestic soybean crush means Chinese dependence on Brazil as a primary source of critical food supply continues to expand and soybean diplomacy may include more Chinese infrastructure investment into Brazil in exchange for supply guarantees. Those guarantees, however, fall apart quickly if the global community wants them to (ask Russian energy companies). Argentina evolving from exporter to potential large-scale importer, at least for the next few years, reduces Chinese diplomatic leverage with the Brazilians.

I wonder if they discussed how to prevent a Chinese invasion of Taiwan with soybean diplomacy?