Insight Focus

- Alternative protein more sustainable than meat on lower land use, emissions.

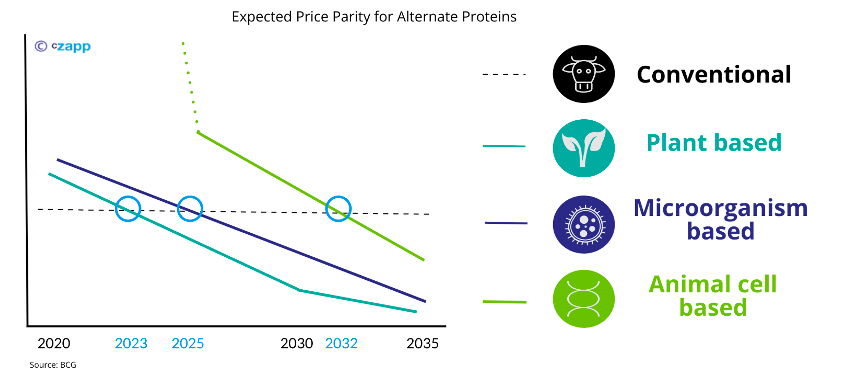

- Could hit price parity with meat by 2023 if demand sustained, operations scaled up.

- Large-scale competition with meat unlikely for at least 10 years on cost.

Is Meat Under Threat?

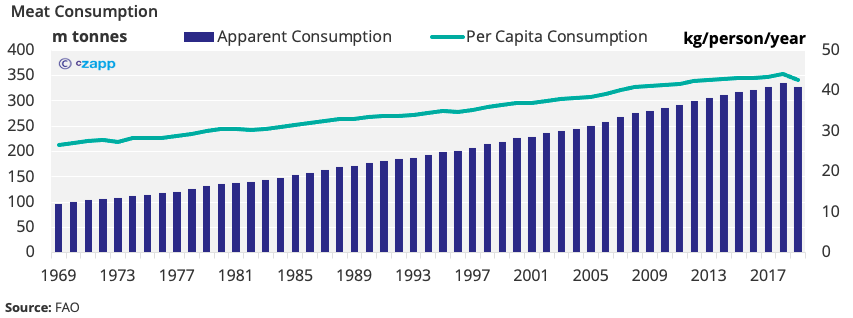

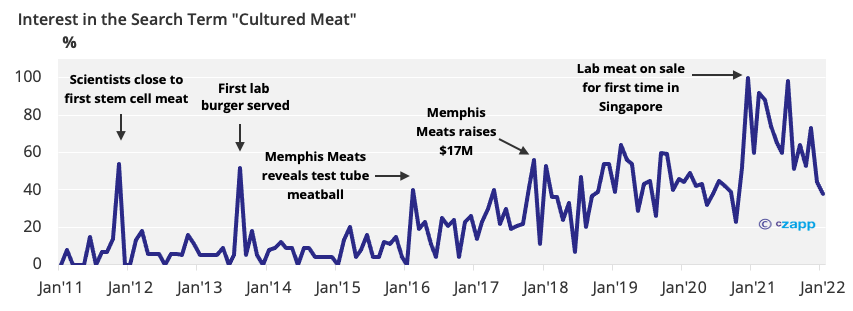

Alternative protein options have been on the market for decades, with some claiming the first veggie burger was developed as early as 1982. But since 2011, demand for alternative protein has increased fast. Meanwhile, global meat consumption fell for the first time in over 50 years in 2019, when the world’s interest in red meat supposedly peaked. However, the FAO expects another rise in meat consumption for 2021.

As red meat tends to be the easiest to replicate with alternative protein, is this a golden opportunity for the more sustainable option to take a stronger hold of the market?

Meat Demand is Intensifying

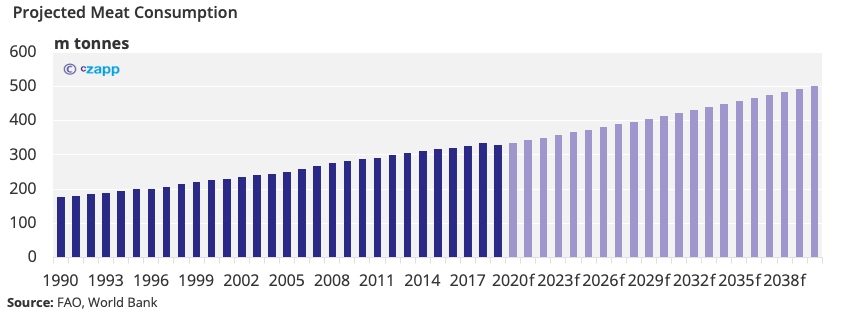

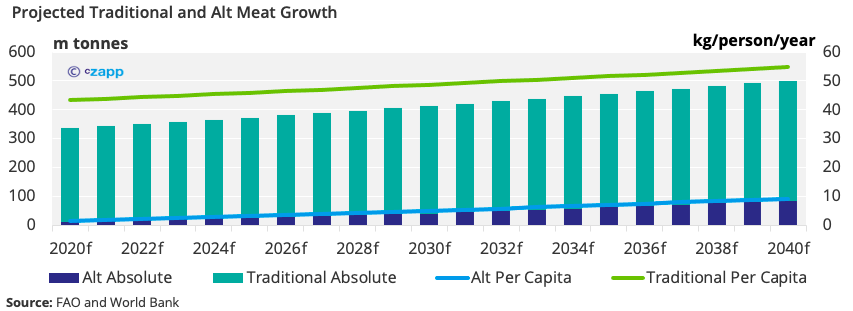

The rising population means meat demands are becoming more intense, with our estimates putting meat consumption at 500m tonnes by 2040 (54 kg/person/year).

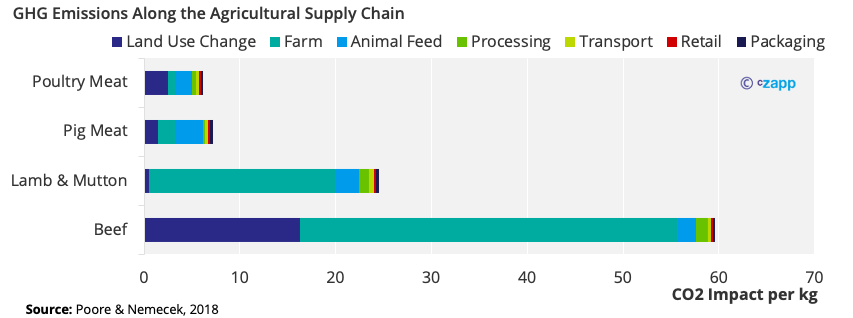

Simultaneously, it’s becoming more difficult for the meat industry to expand. The earth only has a limited amount of land available to further accommodate for more livestock. Also, livestock farming has a concerning environmental footprint, with beef estimated to create greenhouse gas emissions of up to 60kg per 1kg of beef produced.

It’s therefore likely that alternative protein companies will continue to jump on these opportunities, with their products promising a lower carbon footprint, more sustainable production practices and, in many cases, more ethical sourcing of materials.

So, Why Haven’t Alternative Proteins Already Overtaken Traditional Meat Demand?

While consumer interest in alternative proteins is growing, traditional meat consumption is hard-wired into human behaviour.

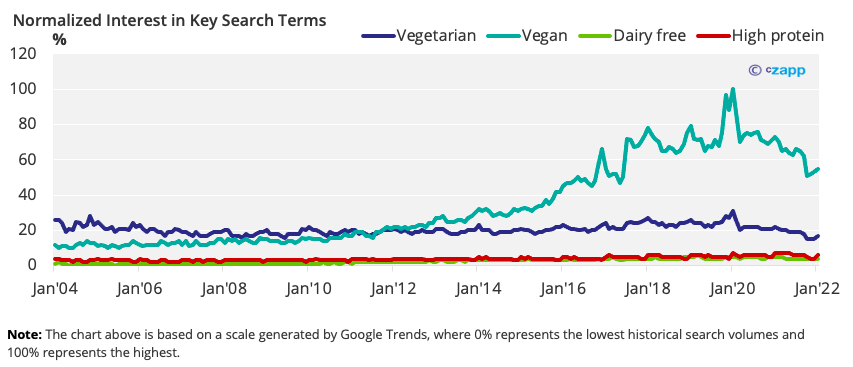

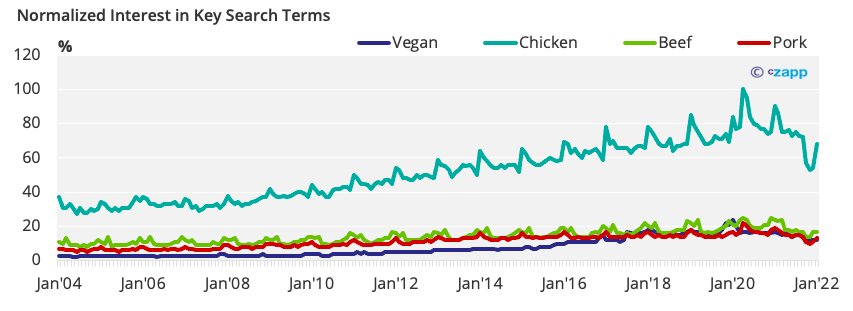

That said, according to Google Trends, searches for the terms vegetarian, vegan, dairy free, and high protein have been increasing since about 2011. The term vegan has grown particularly popular.

Searches for the term vegan reached their peak at the beginning of 2020 after beginning a steep ascent post-2014. This was also the year that Veganuary was launched – a meat free January. This search term then normalised against the remaining three to show that, although the term vegetarian also reached peak popularity at the same time, searches for vegan were far higher.

Interest in the vegan diet has, in turn, generated greater interest in cultured meats. However, cultured meats, although lab grown, still come from animal tissue, which suggests that people aren’t ready to move away from meat entirely.

Interest in vegetarian and vegan alternatives therefore doesn’t automatically signify a willingness to move away from traditional meat products. In fact, in a recent UK survey conducted by OnePoll, 67% of respondents said they’d rather reduce life expectancy than give up meat.

Also, even though interest in vegan diets has increased, it’s dwarfed by interest in meat. Using the same search parameters as before, it’s clear that interest in the terms chicken, beef and pork were far higher.

How Competitive Could Alternative Proteins Become?

The world produced around 13m tonnes of alternative protein in 2020, which is miniscule when you think the world consumes about 325m tonnes of traditional meat each year.

All in all, we think the alternative meat industry could account for 11% of the global meat market by 2035, up from ~2% in 2020. This puts its worth at around $211 billion. This is only a base case scenario, though, and with supportive regulations, the market could be worth double that.

Even with growth, though, there’s no saying that alternative protein will take market share from traditional meat. If alternative meat were to represent 10% of the meat market share by 2030, that equates to 41m tonnes, while traditional meat still maintains about 372m tonnes. By 2040, a 17% market share would equate to 85m tonnes of alternative meat, compared with 415m tonnes of traditional meat.

What’s Holding Alternative Proteins Back?

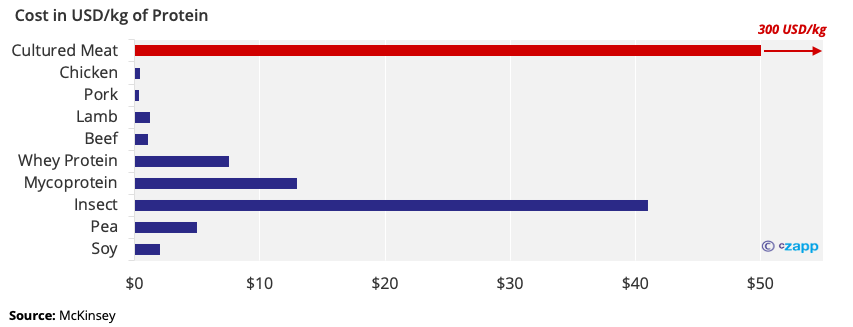

It’s generally acknowledged that, if alternative protein is to truly compete with traditional meat, there are three barriers to overcome: cost, taste, and texture.

While the cost of certain proteins is going down, some forms are still prohibitively high. Plant-based proteins, such as soy and pea, are reasonably affordable, whilst cultured meat remains out of the price range of the average consumer.

To put this into content, Eat Just, the company behind the first commercially available cultured chicken nugget, said in 2019 that the cost of a single nugget was $50. Singapore-based restaurant, 1880, is selling these nuggets as part of a three-plate sample menu costing $23, but the owner has acknowledged that the restaurant is losing money at this price. So, animal proteins remain the cheapest forms of protein, by far.

As for taste and texture, advancements in research and development mean many alternative proteins can now replicate the characteristics of traditional meat.

For example, beef products can include beet extract, pomegranate powder and soy leghaemoglobin, allowing them to maintain the pink-red colour of rare beef. The latter ingredient also makes products appear to bleed just like traditional beef.

Other characteristics are harder to substitute, though. Meat texture is difficult to replicate with plant-based ingredients, given the lack of muscle tissue. Likewise, unique challenges exist in replicating the light, flaky texture of certain fish or the correct seafood-like taste.

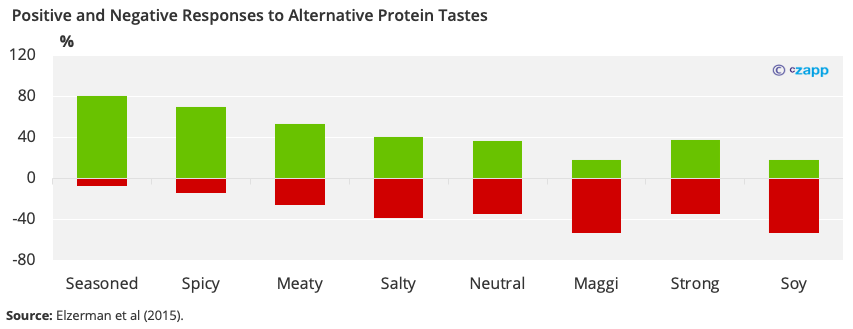

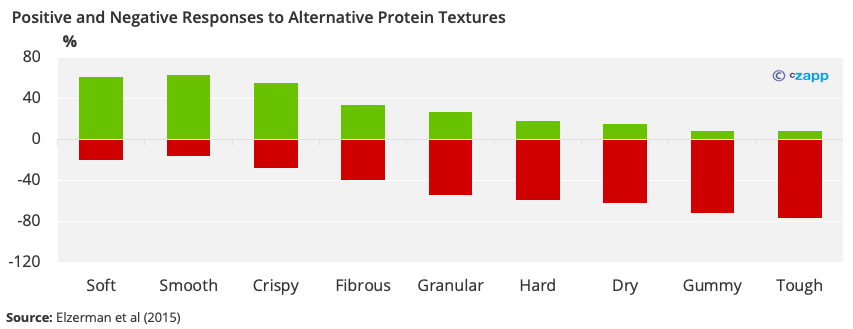

Of course, taste and texture are both highly subjective, but research suggests that there are some characteristics consumers seek out in their proteins. In terms of tastes, seasoning, spice, and meaty flavour obtains a positive reaction, while maggi and soy tastes have drawn a negative reaction.

Likewise, soft, smooth, and crispy textures in alternative meat obtained a high approval rating, while granular, dry, hard, gummy, and tough textures were less favoured.

When Might Alternative Protein Manufacturers Overcome These Obstacles?

There’s no way to predict when alternative protein manufacturers will be able to make products that appeal to the taste and texture preferences of the majority, and there are still a lot of questions from consumers.

For example, there are concerns that adding characteristics that replicate those of traditional meat can lead to alternative proteins becoming ultra-processed, and therefore less healthy. There’s also not enough clarity surrounding the sustainability of alternative protein manufacturing processes.

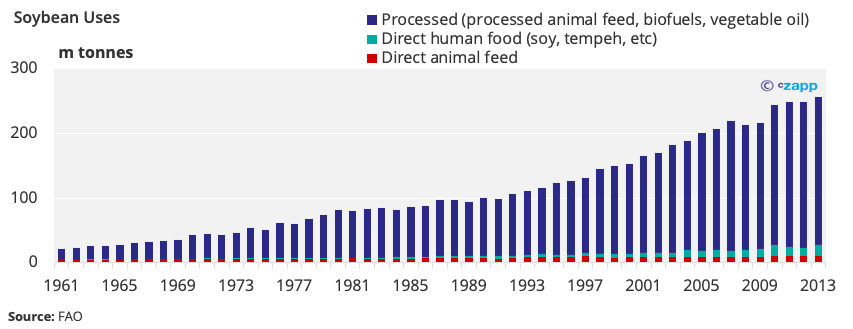

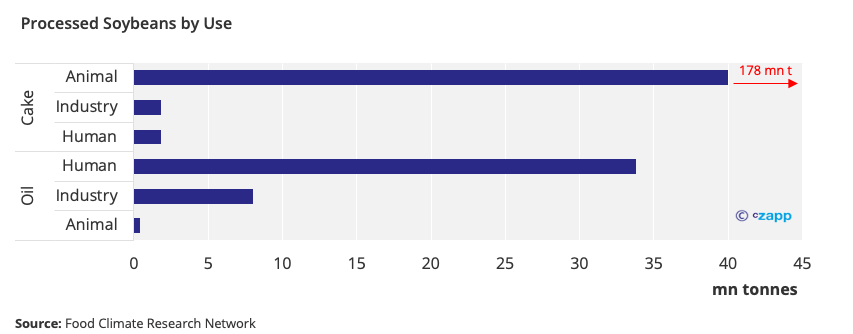

Scaling up could also be a problem. In the case of plant protein, much of the existing capacity already has a use (namely, animal feed). About 77% (~195mmt) of the world’s soybean, for example, is used as animal feed, as are large quantities of pea protein.

Although just a small portion of unprocessed soybean goes to direct animal feed, most processed soybeans are used to feed animals.

So, if these proteins are diverted into large quantities to human food, what will the animals eat? Given that traditional meat consumption is projected to increase on an absolute basis in the years to 2030, this poses a challenge.

In terms of cultured meats, there are question marks over whether a drastic and dramatic scaling up of capacity is feasible in such a short time. The world is projected to need 400m tonnes of meat by 2030. Alternative protein capacity is at 13m tonnes, and the vast majority of that is plant-based protein rather than cultured meat.

That means cultured meat currently holds about 0% of market share. To scale this up to 10% in eight years implies a capacity of 40m tonnes. CE Delft estimates that this would require investment of $1.8 trillion to create 4,000 factories each with 1.3m litres of cell culture capacity. To put this into perspective, these mega-factories dwarf the current largest factory in the world by more than four times.

Concluding Thoughts

While alternative proteins have grown impressively in a remarkably short period of time, the traditional meat industry should have little to worry about in the medium term.

Infrastructure for traditional meat manufacturing has been developed over hundreds of years and the current scale is eye-watering. That said, there’s no reason why alternative proteins cannot duplicate this success, although will most certainly require significant investment.

If alternative protein’s popularity continues and operations can scale up due to higher investment, it could reach price parity with traditional protein by as early as 2023.

And despite its massive size, there are structural challenges faced by the mammoth meat market and these could be addressed by meat alternatives. In the next 10-20 years, there’s sure to be massive developments and significant investments in alternative proteins as the world tries to find a more sustainable solution for meat.

If this can be harnessed effectively, and if cultured meat manufacturing can be scaled, alternative protein could perhaps emerge as a contender in the war for market share. But for now, at least, traditional meat manufacturers can rest easy.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

How Do You Feed 7.9 Billion People?