Insight Focus

- Russian fertiliser export ban hits largest importers, Brazil and USA.

- The USA’s fix looks more feasible in the short term, with grants to be offered in the coming months.

- There are environmental concerns about Brazil’s long-term plan.

The Russian government has advised companies against fertiliser exports, reducing global supply. Brazil and the USA are therefore looking to reduce their dependency on fertiliser imports; they each import around 85% and 70% of what they consume a year. Are their plans to boost domestic production feasible with natural gas prices surging?

Brazil to Cut Fertiliser Imports by 40%

Brazil currently imports around 40m tonnes of fertiliser a year. 9.8m tonnes, or 25% of this, comes from Russia, but these flows are off the table now the government has suspended exports. Brazil is therefore looking to boost production and reduce imports by 40% by 2050 under the National Fertiliser Plan.

Under the plan, Brazil intends by 2030 to:

- Increase its nitrogen production capacity to 1.9m tonnes a year, from 224k tonnes.

- Increase its phosphate production capacity to 4.2m tonnes/year from 1.7-2m tonnes.

- Increase its potassium oxide production capacity to 2m tonnes/year from 250k tonnes.

- Have at least two more nitrogen-based fertiliser production companies, taking the total to seven.

- Attract at least BRL 10 billion (USD 2.16 billion) investment to build nitrogen fertiliser plants.

And by 2050, it plans to:

- Increase its nitrogen production capacity to 2.8m tonnes/year.

- Increase its phosphate production capacity to 9.2m tonnes/year.

- Increase its potassium oxide production capacity to 6m tonnes/year.

- Have at least four more nitrogen-based fertiliser production companies, taking the total to 10.

- Attract at least BRL 20 billion (USD 4.33 billion) investment to build nitrogen fertiliser plants.

It may also increase import taxes to make domestic production more competitive and reduce the emissions associated with importing from overseas.

Parts of Brazil’s plan have come under fire from environmentalists, though, as it’s exploring potash mining opportunities in the Amazon Basin. These raw materials would be used to make phosphate fertiliser in three new plants it’s looking to open by 2040, taking the total to 10.

In the short term, we think Brazil will turn to China, Morocco, and Canada for its supply, which already account for 33% of its imports. Brazil will also look to Iran, having recently signed an agreement to exchange 400k tonnes of soybean and corn for nitrogen fertiliser. In addition, business magnate, Aliko Dangote, has opened a 3m tonne fertiliser plant in Nigeria, which will export to Brazil.

USA Announces Grant Program for Smaller Fertiliser Producers

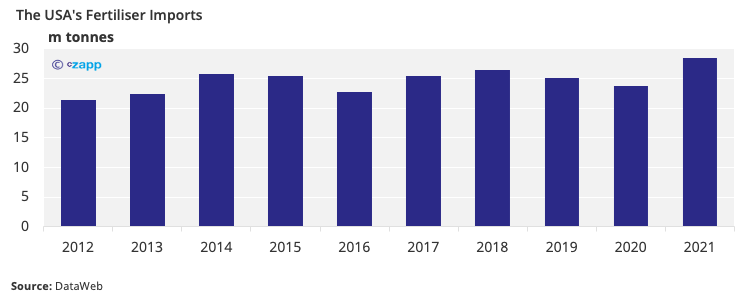

The USA is the third-largest fertiliser importer in the world, with 28m tonnes (80%) of its supply coming from Canada. It’s also the second-largest importer of Russian fertiliser, after Brazil, taking around 3.5m tonnes a year which would be 23% of their total fertiliser supply.

It too is struggling to secure fertiliser, though, so is looking to boost its fertiliser self-sufficiency. The USDA has announced USD 250 million of grants, which will be up for grabs this summer. The grants are designed to help smaller producers finance capacity expansion and improvements to production processes. By targeting greater domestic production, they’ll also address concerns around climate change by reducing transportation emissions.

To combat growing competition in the domestic supply chain, the USDA is also launching a public inquiry in hope that it’ll find out what more it can do to help local producers. The results of the inquiry could see anything from the introduction of new grant and loan programmes, shifts to laws and regulations, or further pushes to boost domestic fertiliser supply. Time will tell.

For the next couple of seasons, though, the US should continue to rely on imports and domestic production. Even with the grants, fertiliser expansion won’t happen overnight, and the country’s producers are currently working at full capacity, delaying maintenance to keep up with increased demand.

The government is also figuring out which other countries it could turn to for supply. Most of the USA’s imports should still come from Canada but flows from Nigeria should also rise as the Dangote fertiliser plant opens.

Concluding Thoughts

The US has enough fertiliser for its current crops. Going forward, it’s looking for alternative suppliers to Russia.

The USDA’s upcoming grants should support smaller producers and help boost sustainable production. The true impact of these measures should be seen within the next couple of years, though.

The results of Brazil’s programme are unlikely to materialise for at least a decade, especially now plans to increase mining in the Amazon are coming under fire. Securing large amounts of investment to help develop plants and improve infrastructure could also take years.

Brazil’s progress may accelerate if the government changes the tax rules to make imports less competitive compared with domestic production. Until this happens, though, it’s hard to judge the feasibility of Brazil’s goals. This means the USA’s plans look more feasible, and the outlook for Brazil’s agricultural industry is less certain.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

How Farmers Are Working Around Fertiliser Prices and Shortages