Opinion Focus

- Brazil might become one of the world’s largest corn exporters.

- Brazilian corn is now cheaper than the US corn.

- Chinese companies turn to alternative suppliers to diversify imports and increase food security.

Director of the Center for Agricultural Policy and Trade Studies of North Dakota State University, in the United States, the economist Sandro Steinbach is considered one of the top voices on global food chains. Last year, he concluded a study about global shipping disruptions during the pandemic and the effects on the U.S. agricultural exports.

Sandro Steinbach, director of the Center for Agricultural Policy of North Dakota University

Steinbach also analyses the possible effects of a less competitive US grain production in the global food trade and how it might impact countries like Brazil. The conclusion is that unless the US reduces its corn prices or Brazilian production become uncompetitive (both unlikely), Brazil will continue to increase its corn exports to China – the largest consumer worldwide.

At the end of 2022, Beijing approved several Brazilian companies that can export corn to China (the list is 400 long). According to market estimates, Brazil may export around 5 million tonnes of corn to China this year – this is 10% of total global corn exports and 194% more than Brazilian corn exports to China in 2022.

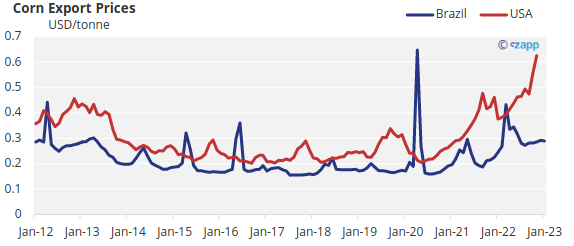

In December alone, just after China and Brazil concluded a corn trade deal, Brazil exported 1.1 million tonnes of corn to China. In January, almost 1 million tonnes were exported. “Since May 2022, Brazilian corn prices became cheaper than the US corn by US$ 0.05 per kg on average”, says Steinbach in an interview to Czapp.

Read the interview below:

China is ramping up corn imports from Brazil: one of the main reasons is the loss of competitiveness of the US corn? Is it cheaper now to buy Brazilian corn than the US corn?

A trend of increasing price difference between the two countries can be observed since May 2022, with Brazil’s average corn export price being lower.

Moreover, it is noted that since 2019 an additional tariff of 10% has been imposed on corn imported from US by China as a measure of trade retaliation.

It is possible that the combination of higher corn export price and the additional retaliatory tariffs has made it difficult for corn importing companies in China to continue sourcing from the United States. As a result, these companies may have turned to alternative suppliers with lower prices.

Source: USDA, Comex.

Unless US reduces its corn export prices, China removes the retaliatory tariffs or Brazil’s corn export prices become uncompetitive compared to other suppliers, it is likely that China will continue to increase its corn imports from Brazil.

How much cheaper was the Brazilian corn last year comparing to the US corn? Do you see this trend continuing in the medium and long term?

Since May 2022, the Brazilian corn price became cheaper than the US corn by US$ 0.05 per kg on average. The USDA’s feed outlook for January 2023 projects a decrease in US corn production because of a decreased domestic consumption and exports.

Sales have been sluggish in comparison to the previous year, primarily due to increased export prices resulting from limited exportable supplies and high transportation expenses from rural areas to export terminals, specially via barge from key locations along the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico.

Source: USDA, Comex.

If the trend of decreased production and increased prices for US corn continues, China is likely to turn to Brazilian corn and other sources to meet their needs in the medium and long term.

In that sense, should China continue to buy corn from Brazil in the future?

This is a to be expected development. China is diversifying its supply chains to be less dependent on supply from the US. That’s a lesson learned from Covid, the shipping challenges and the trade war. Brazil’s corn export prices had also been lower than from the United States during the last 12 months, providing Chinese state-owned importers further incentives to expand purchases from Brazil.

It is common for US corn exports to China to fall during winter. However, the increased exports from Brazil represent a major shift that will, depending on the price gap, continue to exist in the mid to long-run. An additional variable to consider is Chinese demand. Depending on the size of the economic downturn, there might be less demand in the near term. However, I expect diversification will continue to contribute to additional demand for Brazilian corn from China.

Since China is diversifying its supply chains, they might look at a variety of countries and food products? What should we expect in that sense?

We can expect similar patterns we are already seeing. An example is the rise of Ukraine as a major corn exporter to China before the war. These trends will continue and intensify with growing political and trade tensions between the United States and China.

Source: World Bank

Finally, has the United States lost $10 billion in agricultural goods exports during the pandemic due to logistical issues? Why did it happen?

Yes. According to our analysis in our research article (Carter et al., 2022), the US lost around $10 billion in agricultural exports between May 2021 to January 2022. The reason for the losses can´t be solely attributed to the pandemic or the logistic issues. The pandemic initially started the losses for the US agricultural exports, but there´s more to it.

The Government response, the unbalanced trade market, the maritime freights and lack of container are all responsible for the logistic issues that caused the losses for the US agricultural exports.

The drivers for the losses can be summarized in four main points.

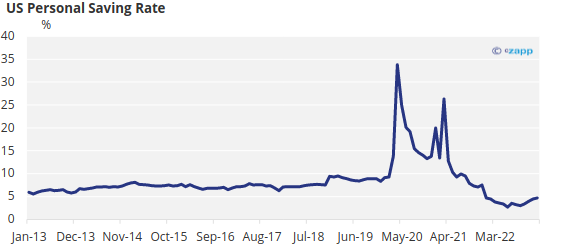

Source: Federal Reserve of Saint Louis

First, the skyrocketed personal saving rate. Since the pandemic outbreak in early 2020, increased unemployment benefits, stimulus checks and deferred consumption expenditures have caused the US personal saving rate to skyrocket by about 14 percentage points until September 2021.

The additional savings allowed the US people to have more purchasing power to buy more durable goods, which were usually imported from Asian countries like China. However, the ports on the West Coast became increasingly overwhelmed by the incoming products, causing congestion in the ports and slowing the turnaround time for the ships that travel around the continents.

Second, the growing demand for durable goods from Asia resulted in a substantial increase in maritime freight rates. In January 2022, the container freight rates from Asia to the United States increased more than six times comparing to the pre-pandemic period while the shipping rates from the US to Asia remained stable.

This shipping rate differential made it more profitable for containers to be sent back to Asia empty instead of waiting several days to fill with US agricultural products.

Third, the slowed turnaround times amplified the issue. The amount of time taken to ship agricultural products from the US West Coast to China reached more than 110 days in January 2022 – back in 2019 it took only 50 days.

This slow turnaround time makes shippers less willing to wait more days in the western ports for agricultural products. They instead chased higher shipping rates by carrying goods from China to the US.

Fourth, the agricultural exporters faced a shortage of containers. Agricultural exporters faced increasing container rental fees, demurrage, and storage fees.

Some agricultural exporters were forced to re-route containers through Texas, Vancouver, or the East Coast at a great expense. Also, many shippers decided to cancel contracts and refused to supply empty containers to US exporters, returning them unfilled to Asia instead.