Insight Focus

Brazil is adopting more and more sustainability-related legislation. Not only can public financing mechanisms for agribusiness make the Brazilian countryside more sustainable, but it can also make Brazil more competitive in international trade.

Agriculture Funding and Legislation Boost Bio Conservation

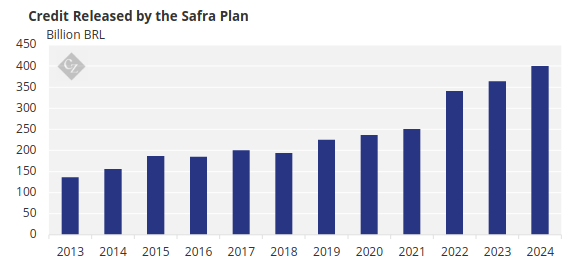

This year, the Safra Plan, a public mechanism for financing Brazilian agribusiness, arrived with new features. The 2024/2025 program grew in resources, with a total of BRL 400.59 billion in funding (10% more than in the previous year).

One of the main features of the program is that it offers credit to farmers at controlled rates of between 7% and 12%. I comparison, normal bank rates are around 12.75%. The expectation is that the Safra Plan will support 35% of agricultural production in Brazil and around 2 million direct jobs.

Brazil nut harvest. Photo: iStock.

Created in 2003 to support the development of agribusiness, the Safra Plan offers lower interest rates for large and small producers, in addition to covering agricultural cooperatives and family farmers. There are specific credit lines for the modernization of equipment and investments in technology, and conservation of natural resources.

In the last ten years, the resources released by the Safra Plan totaled almost BRL 3 trillion. Today, the program accounts for around 30% of all amounts allocated to agribusiness financing – the rest comes from private banks and rural producers’ own resources. Considering that agribusiness is responsible for a quarter of Brazilian GDP, the granting of public credit is more than welcome.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture

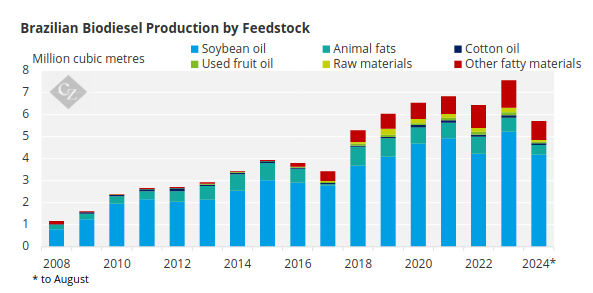

But it is not just environmental legislation or access to credit that has been motivating Brazil to follow the path of sustainability. Market demands and developments such as the Future of the Fuel bill, which encourages the production of biodiesel and other sustainable fuels, also play an important role in this scenario.

Soy Given Sustainability Boost

With this increase in funding for sustainable practices, there is more scope to reduce carbon footprints of key Brazilian crops. Globally, there is a huge focus on cleaner fuels, and Brazil already produces large amount of biodiesel from soy.

Source: Abiove

With financing from Plan Safra and private banks – which are increasingly attentive to sustainability — Brazilian farmers could produce soybeans with a much lower carbon footprint. The Brazilian Agricultural Research Company (Embrapa) intends to launch the low-carbon soy certificate by 2026.

The criteria of the program, which includes the participation of companies such as Cargill and Bayer, are already being outlined. It will be necessary, for example, to use practices such as direct planting and crop rotation. The use of clean energy sources for irrigation and biodiesel-powered tractors will also be considered.

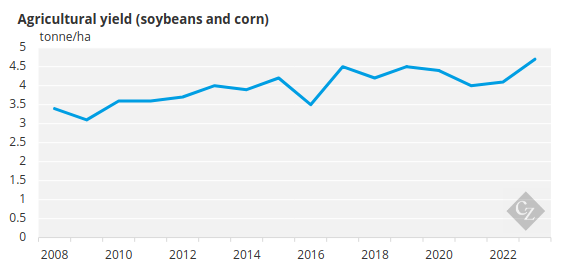

Another key point to understand the advancement of investments in sustainability is the increase in productivity. Several initiatives, such as direct planting and the use of bio-inputs, are related to improving soil health, as they favor the fixation of nutrients. As a result, the soil produces more and better-quality produce.

These practices, together with the advancement of agricultural mechanisation and crop tropicalisation technologies, have allowed continuous yield advances.

Source: Conab

Brazil Embraces Sustainability

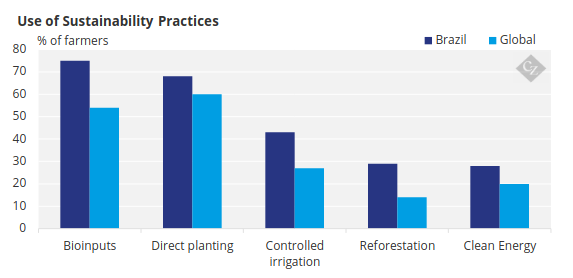

Today, Brazilian rural producers lead the use of a series of sustainability actions, as shown by recent McKinsey research.

Source: McKinsey

The origins of modern sustainability practices in Brazil date back to the 1960s, when public and private rural credit was established. The difference is that, at that time, the granting of credit was more restricted and included few lines of financing, making it less accessible, for instance, to family farmers and agricultural communities who help preserve forests.

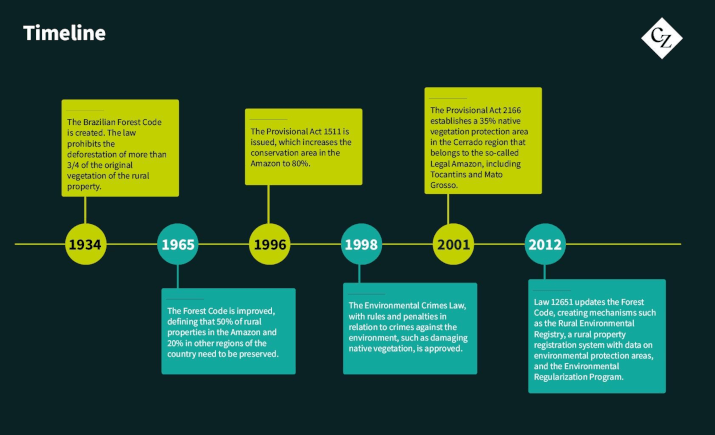

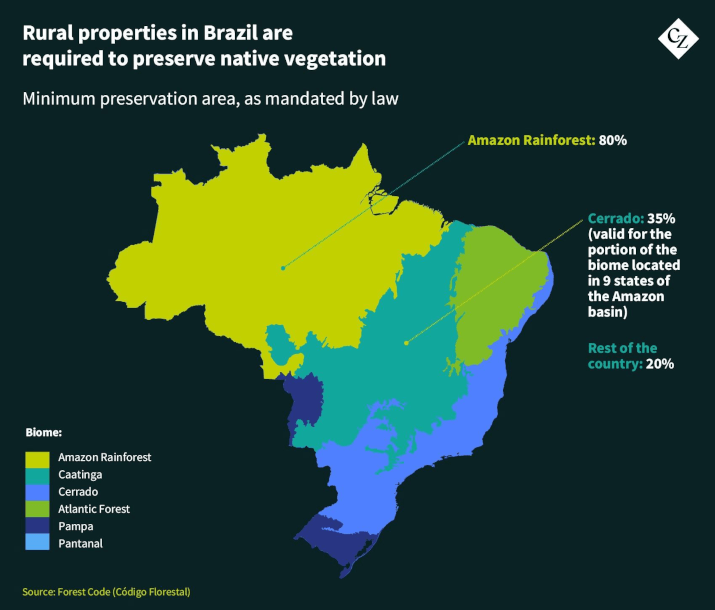

In any case, obeying the Forest Code was already mandatory to access rural credit decades ago – the legislation, created in 1934, evolved until it established environmental regularization programs and stricter rules for the preservation of native forests.

Today, failure to comply with the Forest Code or committing environmental infractions can result in penalties such as criminal detention, fines that can reach BRL 50 million and a ban on continuing to carry out the activity.

“Any illegal practice in the countryside, such as burning, also leads to restrictions on access to credit and insurance, both in the public and private spheres,” explains lawyer Rodrigo Lima, partner at Agroícone, specialized in sustainability in agribusiness and international relations.

Challenges

Farmers and rural entities, however, believe that it is necessary to make sustainability strategies clearer, including for the foreign market. Organizations such as the National Confederation of Agriculture (CNA) and the Brazilian Agribusiness Association (ABAG) have promoted missions abroad in conjunction with the Brazilian Export Promotion Association (APEX).

One of the main objectives is to showcase Brazilian production practices and discuss possible commercial partnerships. In Brazil, sector representatives have participated in events and debates on socio-environmental policies and related topics.

On the legislative side, there have also been efforts to increase the level of punishment for environmental infractions. The intention is for the country to adhere to a higher level of respect for laws and bio conservation, with the goal of being an international pace setter and ultimately positioning itself better in global trade.